In the fall of 1918, World War I was a few months into its fifth year and had become a cataclysm resulting in millions of deaths. But even as the war entered its final weeks, nature inflicted more casualties than had uncountable bombs, shells and bullets in the conflict.

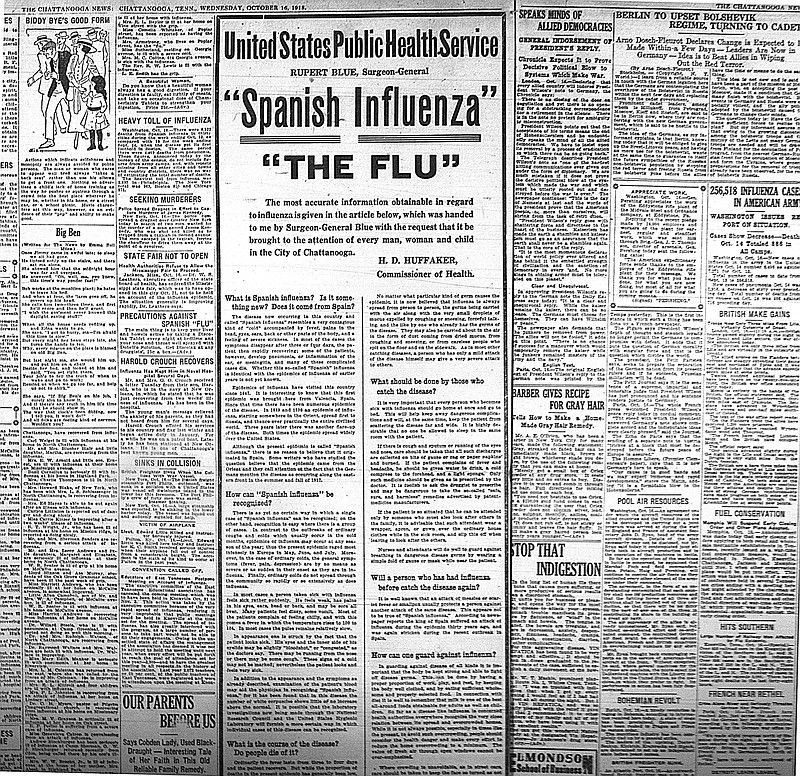

A pandemic of what was then known as the Spanish Influenza (although it apparently had nothing to do with Spain) struck on a worldwide basis. The Centers for Disease Control estimated that one-third of the world's population became infected with this virus. The pandemic caused an estimated 50 million to 100 million deaths worldwide with 500,000 to 700,000 in the United States.

The origin of the flu virus was unknown. It spread simultaneously through North America, Europe and Asia in three waves during 1918-1919. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel in spring 1918, but the spring wave was relatively mild. The virus returned in the autumn of that year with ferocity.

The virus itself usually was not the cause of death. Most victims succumbed to bacterial pneumonia following the influenza virus infection. Mortality was high in people younger than 5, 20- to 40-years old, and 65 years and older. The high mortality in healthy people, including those in the 20- to 40-year age group, was a unique feature of this pandemic.

Young men gathered together at camps and military posts for war mobilization and training, such as at Fort Oglethorpe and Camps Greenleaf and Forrest (on the Chickamauga Battlefield itself), were particularly susceptible.

At first, authorities at Chattanooga thought that the flu might bypass the city. Articles in the Chattanooga News in the third week of September reported the spread of the contagion across the country, but that it had not yet reached Chattanooga or its nearby military posts. Nonetheless, on Sept. 24, federal and local officials conferred on possible precautions should the disease reach the area. As late as Oct. 1, the paper reported that authorities hoped continued warm weather would keep the flu away.

The first week of October, however, witnessed the first deaths in and around Chattanooga. By Friday of that week, there were 12 deaths at the army posts just south of the city. On Oct. 7, theaters were closed, and visitation at the county jail was curtailed, but schools stayed in session with their windows open. Schools were closed on Oct. 9, and public gatherings curtailed. A Baptist Bible conference was canceled. Stores were ordered to fumigate twice a day, keep their windows open and then to close on Oct. 12. As a result, Market Street was expected to be like a "deserted country road." A report published on Oct. 11 estimated there were 2,763 cases of the flu at the posts, and 7,000 cases in the city and its suburbs. By Oct. 21, 99 deaths were reported in the city.

Chattanooga homes were described as becoming small hospitals. Between illness and military service, doctors were in short supply. To the extent not stricken themselves, ministers, banned from conducting church services, visited the sick and conducted funerals. With school suspended, a number of teachers aided the sick in many ways, with one principal and some of his staff setting up a soup kitchen.

As was the case elsewhere, the flu ran rampant for a couple of weeks and then subsided to a significant degree, although isolated cases lingered.

With the worst over, business more or less resumed on Oct. 29. Public business was again suspended on Nov. 11, but only for the happy occasion of the Armistice marking the end of the war.

Assuming that the death toll was reported under influenza rather than pneumonia, total deaths in Chattanooga and Hamilton County from the flu approached 700. How many of those were in excess over a normal year is unclear. Deaths at the military posts exceeded 400. By comparison, Atlanta lost a total of 829 residents, and Nashville a total of 875, a higher death rate because of an outbreak at a large war plant with 35,000 workers in Old Hickory.

Sam D. Elliott, a local attorney and historian, is the author or editor of several books and essays on Tennesseans in the Civil War era, including an award-winning biography of Gov. Isham G. Harris. For more information, visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org.