Read more

Lamar Alexander's No Child Left Behind fix passes through committeeTime magazine names Bob Corker one of the 100 most influential people in the world

It is possible for the United States Senate to work in a bipartisan way, and two Tennessee Republican senators showed just how it could be done this week.

Earlier in the week, Sen. Bob Corker crafted a bill that passed unanimously out of the Foreign Relations Committee that would allow Congress to put eyes on the very important agreement being negotiated by the U.S. and other countries on Iran's nuclear program.

Late in the week, less heralded but just as important, Sen. Lamar Alexander put together a bill that passed unanimously out of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee that would fix the George W. Bush-era bipartisan No Child Left Behind bill.

For the past four years, before Republicans won control of the Senate in 2014, the Senate was a virtual parking lot, with Democrat Majority Leader (and parking lot attendant) Harry Reid keeping legislation from coming out of committees and to the Senate floor for debate. The legislation that he kept bottled up included ideas from Republicans and Democrats, legislation he evidently believed in some way would damage President Obama.

GOP senators vowed 2015 would be different, and they have delivered.

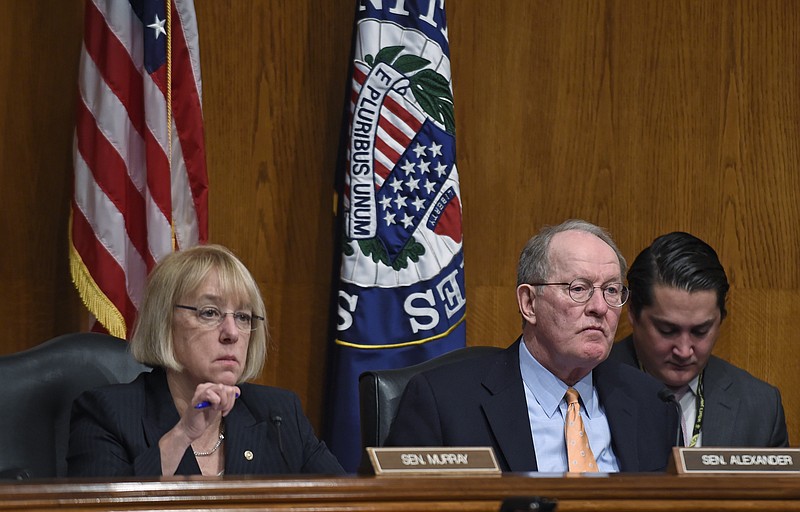

Alexander's bill, which was hammered out with Democrat Sen. Patty Murray of Washington just as Corker's was engineered with Democrat Sens. Robert Menendez of New Jersey and Ben Cardin of Maryland, goes beyond patching the No Child Left Behind legislation.

It would allow states to decide, without influence from Washington, D.C., what academic standards -- such as Common Core, or something else -- they will adopt, would give states the responsibility to determine how to use federally required tests for accountability purposes, and would update and strengthen charter school programs by combining two existing programs into one.

Yet, Alexander pointed out, the Every Child Achieves Act of 2015 continues the original "law's important measurements of academic progress of students" as well as reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which is the chief law governing the federal role in K-12 education.

Similar to the give and take on Corker's measure, the education committee considered 57 amendments to the bill and approved 29.

Alexander, in his opening statement to the committee Thursday, said "presidential action and congressional inaction" are responsible for the present situation, which is that authorization for No Child Left Behind expired in 2007, its tenets had become unworkable, and in the vacuum of congressional inaction, the Obama administration had stepped in with a heavy hand.

What resulted, he said, is oversight by what others called "a national human resource department" and what he often termed "a national school board."

The 2001 legislation, Alexander said, mandated a combined 17 federal tests in elementary and secondary schools and the reports of their results by race, gender, ethnicity and other measures to see which children were being left behind. It, further, created federal standards on whether a school was succeeding or failing, what to do about it if it was failing, and whether or not a teacher is highly qualified.

The backlash over the recent federal control has been so vociferous, he said, that it has drowned out anything worthy about Common Core standards, teacher evaluations and tests in general.

The bill that came out of the committee Thursday, Alexander said, would keep reading, math and science tests and the results reports. It would allow states to determine their lowest-performing schools and how to fix them but would permit federal funds to assist in the fixes. Further, it would allow but not require states to link teacher evaluation to student performance.

What now must be considered, he said, are the 60 votes for full Senate passage and conference committee discussion after the passage of a House bill. Plus, he said, the 50 million children, 3.4 million teachers and 100,000 public schools who must live with the results.

Alexander, in exhorting the committee to show "restraint in search of a result," read a letter from Carol Burris, the 2013 New York state principal of the year.

"Local communities cherish their children and have the right and responsibility within sensible limits to determine how their schools [are run]," she wrote. "The federal government has a very special role in ensuring our students do not experience discrimination based on who they are or what their disability might be. Congress is not a national school board."

Bad ideas on a local level can do only small damage and are easily corrected, Burris said. "Bad ideas at the federal level result in massive failure and are far harder to fix."

Control of schools closest to the student makes much more sense than one-size-fits-all Washington solutions. Alexander, Murray and the rest of the Education Committee see it. Let's hope the rest of Congress does as well.