It's good to see the Chattanooga Police Department trading up.

Not that there is anything wrong with the solid shoe-leather type policing that our officers already are using, but if all goes as planned, Chattanooga police hope in coming months to add another tool.

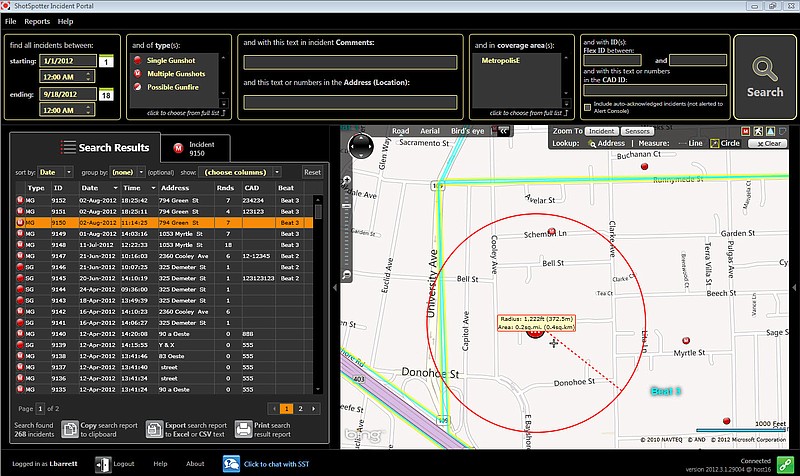

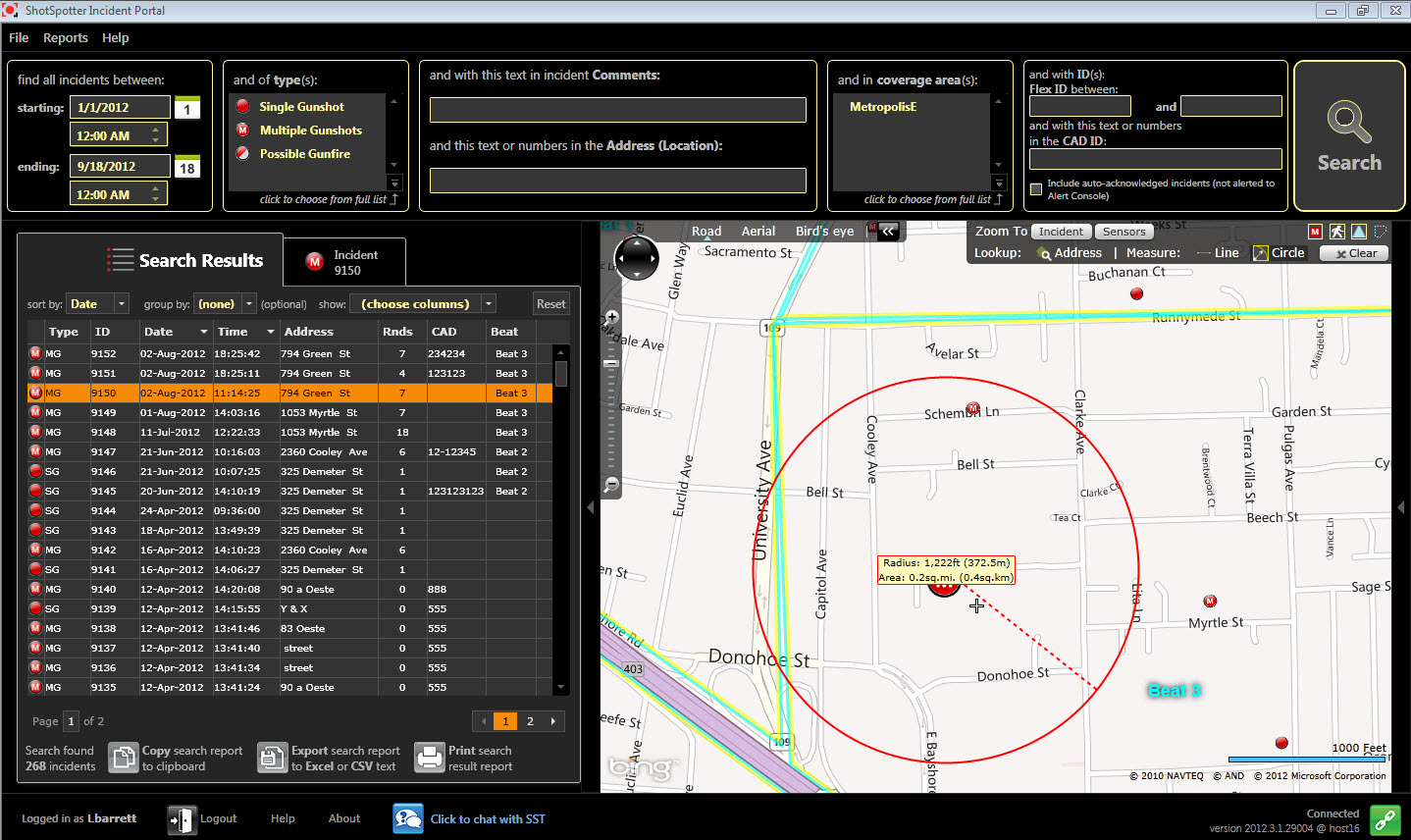

The tool -- a network of microphones and sensors placed around the city -- is called ShotSpotter, and it triangulates the location of gunfire then gets that information to officers faster than most people who hear gunshots can get to a phone, call 911 and make a report of what they heard.

More importantly, in an era when many people don't want to report gunshots in their neighborhoods at all, the system will help police fill in the blanks, according to Police Chief Fred Fletcher, who estimates that currently only 15-30 percent of gunshots fired within the city are being reported to police.

"We had incidents throughout last year where by the time somebody got hurt, the investigation revealed that there were one, two or three shootings previously that nobody reported," Fletcher told Times Free Press reporter Shelly Bradbury recently. "What we'd really like to do is get ahead of that curve. To be in the areas and protecting people before someone gets hurt."

ShotSpotter would cost Chattanooga $270,000 to $450,000 a year, and Fletcher plans to put in a request through the city's budgeting-for-outcomes process to determine whether the city should fund a subscription for about $300,000 -- a deployment of sensors over about a three-mile radius that would include about 20 percent of the city's reported homicides and shootings. The chief said he would like to set up the system in a 4.5-square-mile chunk of town, mostly in East Chattanooga, Highland Park, Orchard Knob and Alton Park -- areas where gun violence is frequent. But the larger the area, the higher the cost, of course.

ShotSpotter, a private company created in California in 1997, is operating in about 85 cities nationwide, according to the company's CEO Ralph Clark.

Birmingham, Ala., is one of those cities, and Birmingham Police Lt. Sean Edwards says it has proven to be an effective tool in reducing response time and deterring shootings. Birmingham has been using ShotSpotter in its most violent neighborhoods since 2007, he said.

"The sensors are pretty accurate. ... We have a lot of people shooting guns, and it's been a good deterrent. We've even had people ask us like, 'How did you guys know to come literally right to my back door?'" he said.

The sensors in the streets record and send information to ShotSpotter's incident response center in California, where experts review the alert and ensure the sensor did capture gunfire, rather than fireworks or a car's backfire. The alert is then sent back to police. All in seconds.

On average, it takes 45 seconds from the time the shots ring out for the alert to hit an officer's in-car computer, Clark said. In addition to pinpointing the location of gunfire, ShotSpotter can also give officers a short audio recording of the shots and can determine whether the incident involves multiple shooters or automatic weapons.

The sounds are analyzed in California because that work takes special training and skills normally too specialized for rank-and-file community police departments. If Chattanooga does deploy the system, the city could become the first in Tennessee to use it.

Technology can be a huge help in fighting crime, but it will still take officers on the ground, acting on the information gleaned from that technology, to see the desired result -- a reduction in shootings and a reduction in violence.

We have that good asset in place already, but if this technology works as well as advertised, it would be a valuable aid.

It sounds promising.