The August air hot and heavy, the sun burning halogen bright that sweltering afternoon in 1993, the last thing Tawambi Settles wanted to do was melt through another McCallie School preseason football practice.

"But then Coach (Pete) Potter showed up wearing a toboggan cap, a heavy winter coat and a big scarf and said, 'Boys, it's cold out here,'" Settles - now a husband, father and McCallie faculty member - recalled this week.

"He instantly made practice bearable. He always knew the right thing to say or do at the right time."

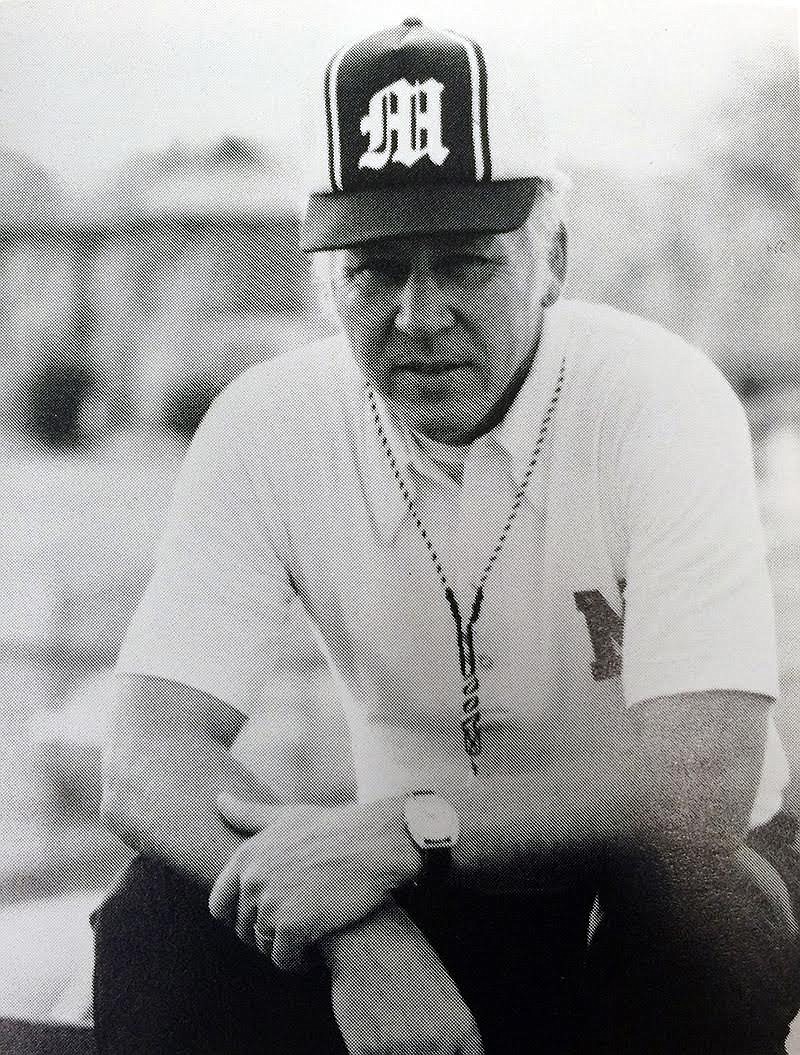

Twenty-two years after Potter coached the last of his 221 games, McCallie will do the right thing tonight by permanently dressing its artificial turf in proper attire for all seasons when it names the playing surface of Spears Stadium "Pete Potter Field" a few minutes before the Blue Tornado host Ensworth at 7:30.

Some might say that stamping those large blue and white letters into the field's plastic grass is a gesture long overdue. Others might say the timing is perfect, what with Pete's son Ralph firmly entrenched in his second tour of duty as the Big Blue boss after winning the school's first state title in 2001 during his initial head coaching stint on Missionary Ridge.

Said headmaster Lee Burns, who graduated from the school in 1987: "Pete Potter always embodied McCallie's ideals. He never cut corners. He believed in hard work, in doing things the right way. It's always important to remember and honor our history and the legendary figures of our school, and Coach Potter was clearly one of those figures."

Leaving behind a Brainerd High School program that he'd once led to an undefeated season, Potter's first year at McCallie was 1973. His last was 1993, right before he began a long, losing battle with cancer. In 21 seasons he won 155 games and lost 66 with a brutally efficient offense, rock-ribbed defense and unbending, unwavering principles.

"McCallie was the place he could come and be himself," Ralph Potter said. "He appreciated McCallie's approach to athletics and football. For both me and our whole family, it means so much to have this recognition for the kind of man he was."

Never was that portrait of Potter the man on larger display than the 1982 season, when the coach discovered that a number of his best players, including the starting quarterback, had broken team rules on the weekend before the annual armageddon with archrival Baylor School.

Despite a number of parents pressuring headmaster Spencer McCallie III to let the young men play, Potter stood firm. They would be suspended for at least the Baylor game.

"It's a difficult thing to lose a crucial player or two in a crucial game," said McCallie, who served as headmaster for all but Potter's first season. "I asked one question of Pete before I met with these parents: Did the players fully understand the rules before they broke them? When Pete said they did, I decided that I would never overrule Pete Potter. He already had a strong reputation of being a fine football coach and a very good man before we hired him. But once he was on campus, I always felt so fortunate that he was our coach, and that decision has certainly stood the test of time."

But if the headmaster had to take some heat, the players who hadn't broken rules had to take the field against the Red Raiders without several of their stars.

"That was an era when you did what you were told to do," recalled Peter Hunt, one of the few key members of that '82 squad who wasn't suspended. "Coach Potter was tough, but you always knew he cared about you. He certainly wanted to beat Baylor that year, but the win he really wanted was the character victory."

In true storybook fashion, Hunt - then a junior - returned a short Baylor punt deep enough into Red Raiders territory for Bodie Spangler to kick a field goal that made the Blues a 3-0 winner.

"He was all about teaching important life lessons," Hunt said. "Coach Potter was iconic, like Yoda, almost a grandfather figure at times."

This isn't to say everything was serious with Potter.

Lentz Reynolds, whose son, Lentz IV, is a McCallie sixth-grader, recalled a Potter quote from just before the 1986 season, when his coach told this newspaper, "We're small, but we're slow."

Retired McCallie athletic director Bill Cherry - who not only hired Potter but also was an assistant coach under him for 11 years - recalled the night he accidentally locked his head coach in the McCallie gym prior to a big game against Soddy Daisy.

"By the time I realized what I'd done, it was time to kick off," Cherry said. "I sent a manager to let him out. Pete raced toward the sideline, hoping not to miss a play from scrimmage. When he got over there he looked at me and said, 'Bill, you're not going to believe this, but some fool locked me in the gym.' I didn't have the guts to tell him that fool was me until after the game."

Spence the Third, as the headmaster often was called, remembered handing Potter "some cockeyed play I'd come up with before every Baylor game. I don't think he ever ran one of them, but he accepted every one of them with mock seriousness."

Ralph Potter, now 52, still laughs at his dad's instructions at the end of many practices.

"He'd say, 'Now go get some beans,'" his son said with a smile. "I still don't know why."

Ralph also said, "When you hit my age, you begin to see your father in you in all kinds of ways. But I've never felt pressure to be like him. He always made sure to tell me to be my own man."

How they all see him is as an extraordinary and extraordinarily humble leader of men.

Said Tom Clark, class of 1975, who quarterbacked the 29-7 playoff win over Baylor at Chamberlain Field after the Red Raiders had crushed the Blue Tornado 33-14 during the regular season: "Coach Potter was a wise man who knew the proper way to deal with teenage boys. He gave us ownership by allowing us to participate in some decision making."

Said Ward Nelson, who went on from that '74 team to become a Morehead Scholar at North Carolina: "He never talked about himself, even when you asked. He was a Golden Gloves boxing champion and a graduate of Virginia (where he was team captain in 1953). But he could care less if anyone knew any of that. When Dean Smith died, a broadcaster remarked that Coach Smith didn't use profanity because he didn't have to. That is exactly how Pete was. I never heard him curse."

Added Kenny Sholl, McCallie's dean of students and a former football assistant: "I could get pretty fired up when I was younger, and it was all about winning games. Pete grabbed me one time and said, 'It's not about that. It's about them competing.'"

In a reception and dinner tonight prior to the game, so many of Pete's players are certain to compete for who'll have the best story. There's even a rumor that the family might break out Potter's favorite brand of victory cigars for those players, as well as dressing the current team in all blue, as was the late coach's custom over the last 14 years he ruled the McCallie sideline.

But that's not why that plastic grass will be known forevermore as Pete Potter Field.

"For hundreds of his players at both Brainerd and McCallie," Nelson said, "he was like our second father."

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com