Twenty years ago in the town of Whitwell, Tennessee, a thought-revolution was underway. If the town didn't know it at the time, it's because they could not have imagined what one simple question - and, more importantly, what one middle school principal's brilliant refusal to render a simple answer - would unleash. But the tiny mining town of approximately 2,000 people, 99.9 percent of whom were white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, would soon become the unlikely site of a Holocaust memorial.

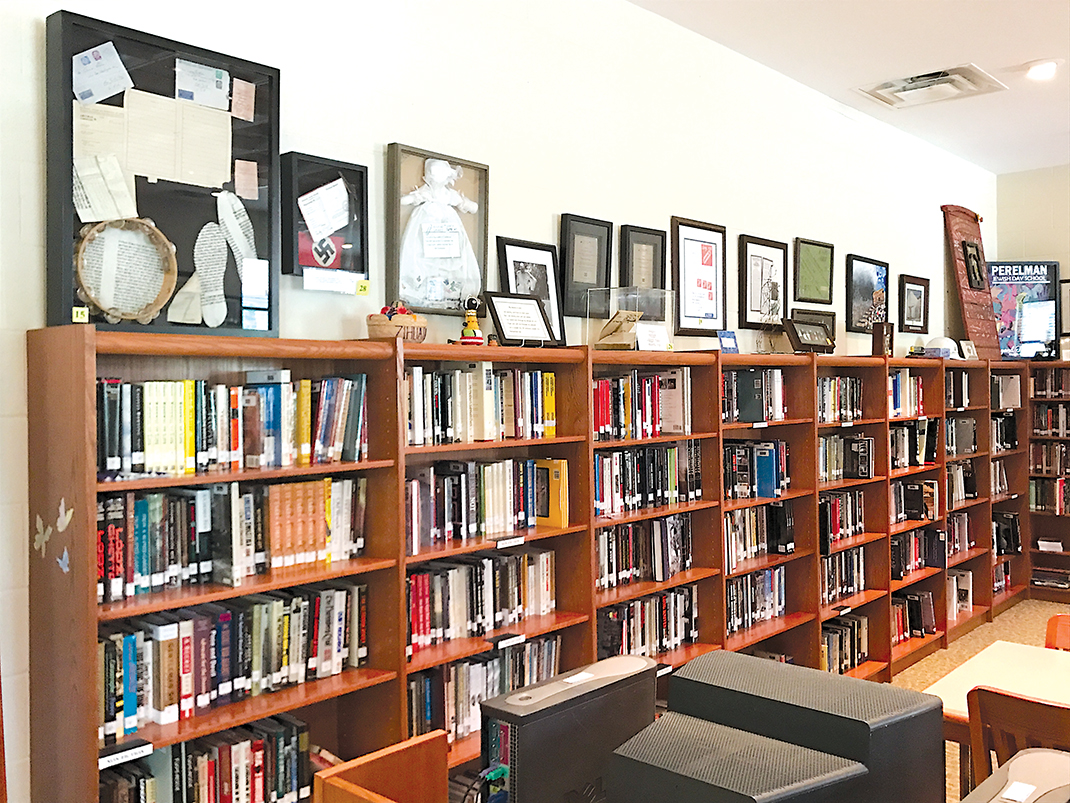

The creation of the Children's Holocaust Memorial at Whitwell Middle School is a moving story of passion, creative vision, faith and teamwork. It has brought hundreds of thousands of tourists to a town that, prior to the museum's creation, few had heard of. The memorial and its genesis would become the subject of a documentary film, "Paper Clips," which would be shown around the world. And it would be the impetus for an international service-learning curriculum, "One Clip at a Time," that would eventually boast 400 educators trained in 29 states plus Canada and Israel.

We at Chatter decided to look back to the inception of the memorial two decades after the fact, and to ask a few of those involved about the impact of the project on them, and on the town of Whitwell.

"Within the school, there was little tolerance for diversity, and bullying was becoming a problem," she says. "Kids were, like their parents and their grandparents, choosing the familiarity of the small town of Whitwell over outside education or exploration. And many of the kids who did leave town after high school had difficulty adjusting, and returned."

So Hooper hatched an idea. She asked associate principal David Smith and language arts teacher Sandra Roberts to start an after-school program. They would look at the Holocaust and at other humanitarian atrocities and genocides worldwide. They would talk about prejudice, hatred, stereotyping, tolerance and diversity at home and abroad; about other cultures and ways of thinking; and about what could be gained, personally and globally, from entertaining a broader, more inclusive worldview. Attendance in the program would be completely voluntary.

That first year, 40 students enrolled.

"The response was overwhelmingly positive," Hooper says. "Kids who'd never interacted or who had been hostile to one another began finding common ground. In-school fighting diminished. Children who had shunned one another began sitting together in the cafeteria." The school officials knew they were onto something important, and decided to offer the program again the following year.

Then a student posed a now-historic question that would set the program, the school and the town on a much larger course: "What does 6 million look like?"

Norwegians commonly -- yet mistakenly -- attributed the invention of the paper clip to countryman Johan Vaaler, and it became a symbol of unity and resistance in the Nazi-occupied country during World War II. This commemorative stamp is dedicated to Vaaler, but shows the Gem paper clip, already in existence when he received his patent for a different design in 1901.

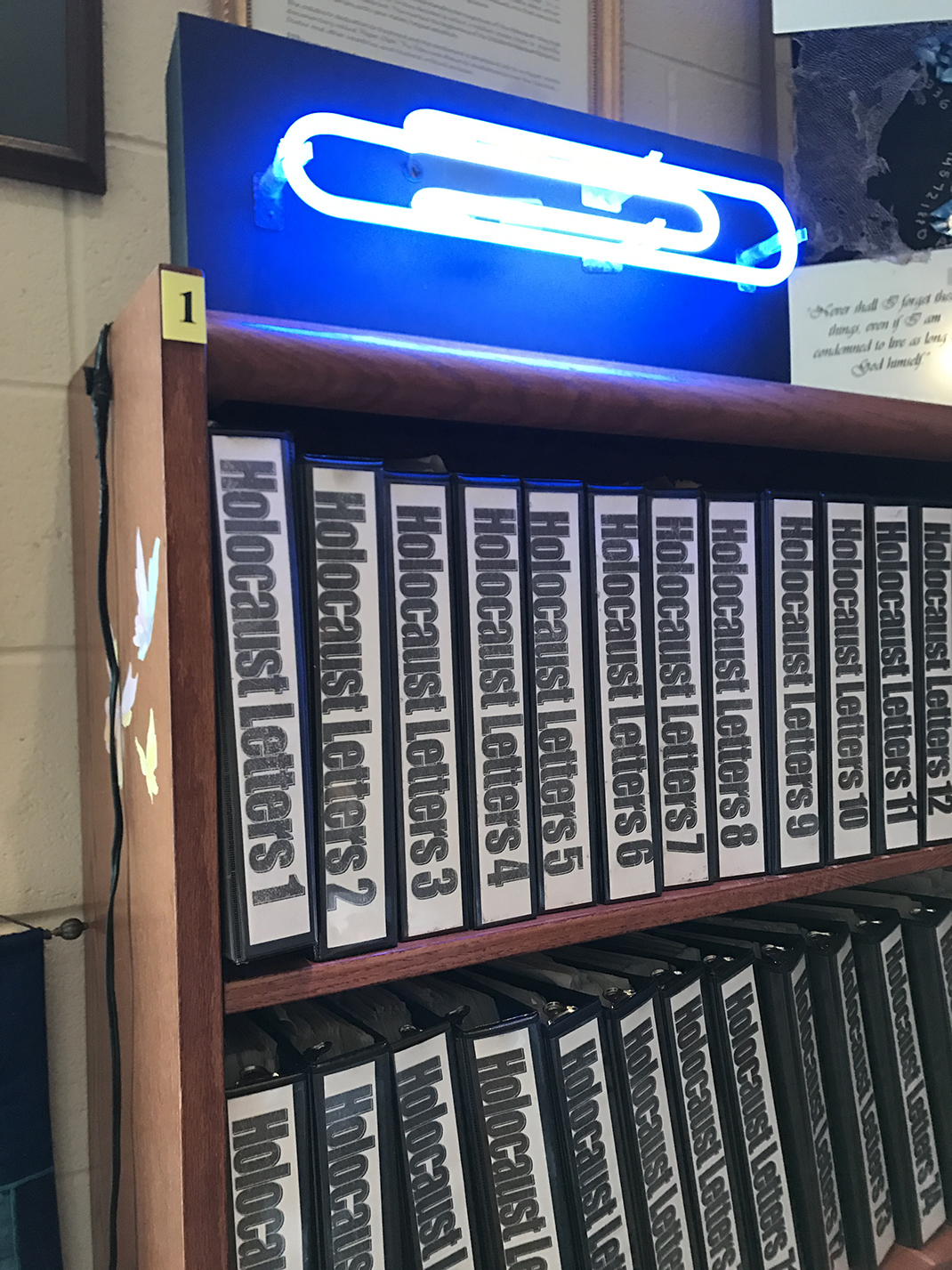

Norwegians commonly -- yet mistakenly -- attributed the invention of the paper clip to countryman Johan Vaaler, and it became a symbol of unity and resistance in the Nazi-occupied country during World War II. This commemorative stamp is dedicated to Vaaler, but shows the Gem paper clip, already in existence when he received his patent for a different design in 1901.Kids and teachers got together and crafted letters to relatives and friends, world leaders and celebrities, telling about their study program and their goal to collect 6 million paper clips. As clips poured in from all over the world (they stopped counting at 30 million), so did letters of support and encouragement. They received 30,000 letters, from all seven continents and almost every state, penned by Holocaust survivors and their families, famous people, political figures, students and the general public. Every letter was read and catalogued and placed in large binders.

In 2001, the school received a donation of an authentic German rail car that the Third Reich had used during World War II to transport prisoners to camps. It was installed for free in front of Whitwell Middle, and 11 million clips - representing the 6 million Jews and 5 million gypsies, homosexuals and other victims of the Holocaust - were poured into it. They are on display behind a clear wall on the train; a visual, profoundly moving representation of the magnitude of lives lost.

Chattanooga resident Alison Lebovitz is president and founder of One Clip at a Time, the nonprofit teaching service curriculum structured around the documentary film "Paper Clips." She got involved in the summer of 2007 with the goal of figuring out how to make the film accessible to more schools. "No one's going to watch an 86-minute-long film in school," she says.

Realizing that the film was structured around five more or less natural "clips" (no pun intended) gave her committee an idea. "We aligned each of the five clips with a lesson plan," Lebovitz says. They named the curriculum, fittingly, "One Clip at a Time."

"The mission of One Clip at a Time is exponentially greater than the nonprofit's original goal of simply getting the documentary into more schools," Lebovitz says. "Instead, our goal is to empower teachers to empower and inspire students to make the world a better place. Specifically, we give students the tools to ask the right questions. What can students do to make an impact, to help senior neighbors, to eliminate pollution, to aid student in need? What do those things look like on a daily basis? How can they not only understand, but also address those needs and make a real difference? That's all in the One Clip at a Time teaching kit, and our goal is to reach as many people as possible with it."

Two decades after tackling the topic, Whitwell is still a town of fewer than 2,000 people. It's still overwhelmingly white Protestant and there are still no Jews, no Muslims and no Catholics. The town itself has not changed. But what has changed, says Lebovitz, is how the town is viewed. The Children's Holocaust Memorial brought the world to the small town's doorstep and has allowed people there to gather around a common cause; to be known for something other than their small town-ness, their insularity and the challenges of their mining economy.Resident Taylor McDaniel remembers helping to count paper clips in her social studies class. She was in the fifth grade when the rail car was dedicated.

"I watched in awe as it was lowered onto the tracks, and I remember the paper clips pouring in. I couldn't wait until I was old enough to join the Holocaust education group and learn more," she says. That chance would come when she was in the eighth grade. Not content to just be in the group, McDaniel also signed up to give tours of the rail cars to visitors.

Now an eighth-grade U.S. history teacher at Whitwell Middle School herself, McDaniel co-teaches the One Clip at a Time curriculum with her former eighth-grade teacher, Sandra Roberts, and is currently working on her Masters in Holocaust and Genocide Studies from Gratz College in Philadelphia.

McDaniel echoes Hooper's reasoning for starting the after-school education group at the middle school.

"Before the project, students here had very little knowledge of other cultures and religions. It's important for them to understand that there is a world outside of Whitwell," McDaniel says. "As a result of the program, they are learning to be respectful of different cultures, and to speak up when they think someone is being treated wrongly. We now have students leaving for college with a better understanding of other peoples, and they are better prepared for the world - it shows as students succeed in their fields. The impact has been immeasurable."

McDaniel says she is always amazed at the number of people who know of the Children's Holocaust Memorial and "Paper Clips" documentary when she travels.

"Just last week, I was presenting at the National Council of Social Studies in San Francisco. A Holocaust survivor told the audience that the reason he started telling his story was because he watched ['Paper Clips']," she recounts. "He has now told his story 150 times this year simply because he thought what we were doing in small-town Tennessee was important. That is powerful."

When Whitwell resident Mary Jane Higdon's oldest son Jonathan was in the seventh grade, she participated in Holocaust classes with him. Little did she know that the project would become a major part of their lives for almost 10 years."I don't think in the beginning I realized the importance of the project," she says. "I was just a mom trying to stay involved in my kid's extracurricular activities."

Ultimately, Higdon's other son, Gregory, as well as one nephew and four nieces would also become involved with the project.

"It became more and more important to me for them to know that not everyone in the world looks, acts and worships the way we do; that there are so many cultures out there, and in order to not be afraid of people from those cultures, we need to get to know them," Higdon says. "[Teacher] Sandy Roberts would haul mail crates to our house and we would sit in the floor at night and open letters and record them. The stories left a mark on my heart that I will never forget."

There was a retired widow who sent a dollar and some change to help in whatever way she could. There was a Holocaust survivor who told of the horrors of a concentration camp.

"I think we were all surprised at the number of letters we received," Higdon says.

And although there were negative letters as well, from Nazi sympathizers, Holocaust deniers and white supremacists, they amounted to only one binder-full.

Higdon and her boys would become part of the documentary built around the project, and she calls it "one of the greatest experiences of our lives." Her family formed a friendship with the movie crew that lasts to this day, a result of their long talks and shared tears.

Similarly, Higdon says the Children's Holocaust Memorial has brought diverse groups of people together, to a community "where residents don't even leave the county if they don't have to."

"Even if someone didn't want to get to know 'strangers,' they kind of haven't had a choice," she says, "and it has been interesting to watch the interaction between folks. I dare say both sides have impacted the other in a mostly positive way."

According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the majority of children arriving at camps like Auschwitz were sent directly to the gas chambers upon arrival. Some, however, were chosen for dangerous science experiments or forced manual labor. Pictured here, child survivors of Auschwitz don adult-size prisoner jackets.

According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the majority of children arriving at camps like Auschwitz were sent directly to the gas chambers upon arrival. Some, however, were chosen for dangerous science experiments or forced manual labor. Pictured here, child survivors of Auschwitz don adult-size prisoner jackets.Still, the project's endurance surprises her. "I never thought when I became involved almost twenty years ago that I would still be getting messages from Linda Hooper asking me to talk to folks like [Chatter magazine]."

Says Lebovitz, "We will never know the full impact of the project because it's still rippling out."

And all because a middle school principal refused to give a simple answer to a question.

If you go

Self-guided tours are available. Visitors may gain access to the rail car by picking up a key from Castle’s Grocery at 13563 Highway 28 between the hours of 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. Central. The store can be reached at 423-658-6542.Student-led tours are offered on Fridays beginning at 9:15 a.m. (Central) when school is in session. To book, visit whitwellmiddleschool.org, download the CHM reservation form and fax it to 423-658-6949. Or email LHOOPER@mctns.net with the word VISIT in the subject line.