Fifty years ago Tuesday, the U.S. launched a rocket from Cape Kennedy, Florida, that would send three astronauts to the moon.

Nothing since the space race that culminated in that moonshot has given Americans such pride in their country.

A pity, that.

Even in the late 1960s, with an unpopular war raging in Vietnam, protests on college campuses and civil rights demonstrations in the streets, the U.S. had one cause that united its citizens.

The goal, after all, was to beat the Soviet Union to the moon. The country's martyred president, John F. Kennedy, had ordained it.

Americans, in the early years of that decade, believed the country was losing the space race, something unthinkable to a generation that had helped win World War II slightly more than 15 years earlier. But the USSR had launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, put the first animal in space and then put the first man in orbit.

So Kennedy, with no particular space fascination if a new book by historian Douglas Brinkley is to be believed, wanted to see what could be done to demonstrate U.S. superiority in space. Putting a man on the moon, he was told, was a possibility, albeit an expensive one.

The U.S., the young president said before Congress on May 25, 1961, "should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth."

At first, Americans were wary. A Gallup poll said 58% were opposed.

But by Sept. 12, 1962, minds had been changed. The U.S. had put a man in space, and another one had orbited the Earth.

On that day, at Rice University in Houston, Kennedy said, "We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too."

Such can-do spirit pervaded the minds of U.S. workers and was hammered by teachers into the psyches of American schoolchildren. We can do it if we put our minds to it.

Through the mid-'60s, the race seemed neck and neck. U.S. USSR. USSR. U.S.

The study of fractions stopped, and televisions were rolled into classroom for students to observe space launches. The answer by most boys - and perhaps a few girls - to the question "What do you want to be when you grow up?" was very often "astronaut."

Toys, games and television shows all picked up the theme.

The momentum was delayed by the 1967 tragedy of Apollo 1, in which three astronauts were killed in a training flash fire, but it didn't stop. The goal was a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

Americans were confident. But astronaut Neil Armstrong, who would take the first step on the moon, told Brinkley the mission was no sure thing. When it lifted off on July 16, 1969, he said, it had about a 50-50 chance of succeeding.

Then-President Richard Nixon, the historian and "Moonshot" author said, was worried about blame falling on him if something went wrong with the mission and there were "dead astronauts in space." Of course, when it all went well, he was only too glad to revel in the success.

Kennedy had felt, according to Brinkley, that winning the space race "would convince countries in the world that democratic capitalism was superior to totalitarianism of the Communist stripe."

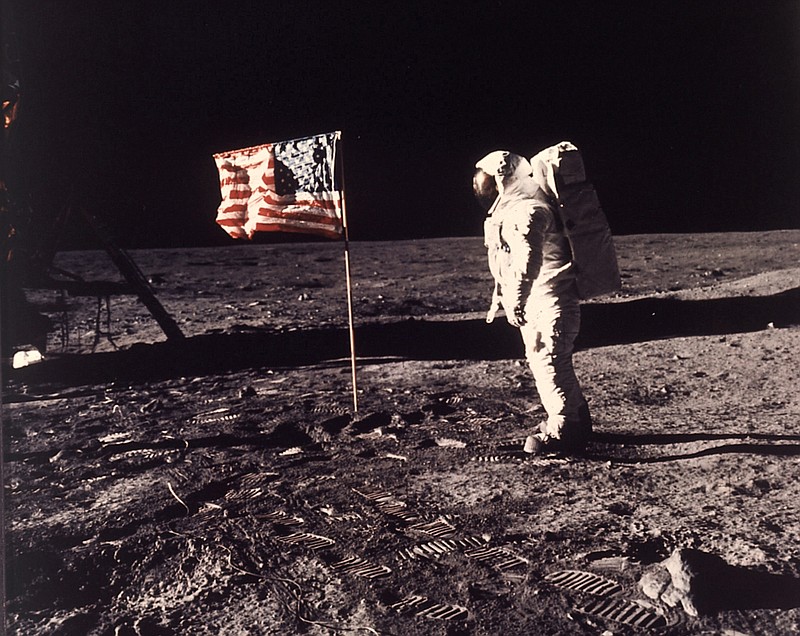

If nothing else, Apollo 11, and the subsequent five U.S. moon missions, seemed to put a quietus on the Soviet space program. At least, the USSR never attempted to put a man on the moon. And something about the U.S. winning the space race made it seem inevitable to Americans that the USSR would never be ascendant again. Indeed, 22 years after Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin first walked on the moon, the Soviet Union collapsed.

Today, though, not only is there no such unifying mission as space for Americans to embrace, but a frightening number of U.S. citizens of Kennedy's political party also believe the same type of totalitarian regime he hoped would be seen as infinitely inferior is seen as a better option for our country.

Then and now, some people shake their heads at the cost of the moonshot - $24 billion between 1960 and 1973 - and wonder what we accomplished since some children born at the same time as the last Apollo mission are now grandparents.

However, medical inventions such as the CAT scan and MRI, kidney dialysis machines, heart defibrillators, GPS technology, firefighter apparatus and anti-icing equipment for aircraft came out of the program.

But the most important takeaway, at the time, may have been the unifying pride the country had, even in a time of division. Would that we had even a measure of that today.