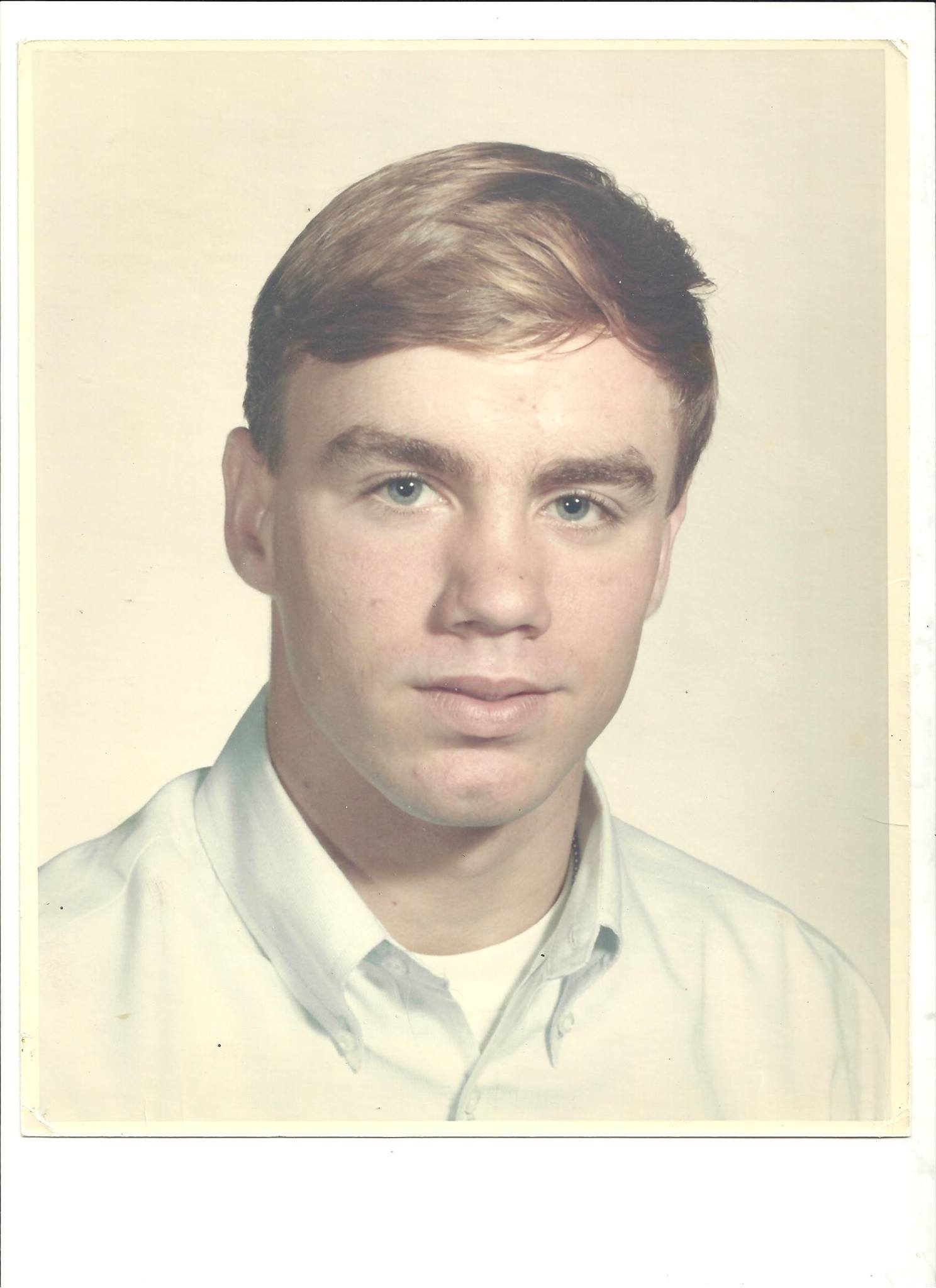

It was on this day, 51 years ago, that my little brother Ricky's body was pulled from the river. His death changed my life. He was my favorite brother, the one I always looked out for.

When the phone rang early that February morning, my great-aunt Sis said she felt something wasn't right. It was Dad calling. There had been a party up at a cabin on the river. Two boys were missing. One of them was his youngest son, Ricky. Dad's aunt, Sis, we called her, could hear it in his voice. Controlled panic.

She knew Dad well. He was her nephew. Sis took him into her home after his grandparents fell ill and became too old to look after him. Dad lived with Sis and her husband, Uncle James, and their son, Jimmy, until he graduated from high school. Uncle James, a gruff man, wasn't crazy about having another mouth to feed. Money was tight.

My great-grandparents, Will and Mamie Stamps, adopted my father after their daughter, Dad's mother, Sis's sister, died from complications associated with his birth. Dad blamed himself, all of his life, for his mother's untimely death.

The story goes that Dad's father, Bill Rogers, was a fast-talking ladies man from Texas who was always thinking and talking about how to get rich. He never did. After the funeral, he moved in with Mamie and Will for a short while. Then, one morning, Mr. Rogers got up from the couch and said he was going to the store. He never came back. Nobody went looking for him.

Sis was the closest to a mother figure Dad ever knew. She was petite, small-boned and spoke with a little voice. She curved her R's. That's Old South. I'd sit on the front porch swing with her, and she'd say, "Do you see all the pwetty buyds in the twees?"

A modest lady, she had grown up in a strict, hard-leaning Methodist family in one of the better neighborhoods of Nashville. Conservatives. Her family gave 10 percent of their weekly earnings to the church.

Nobody could believe that Sis accepted Uncle James' hand in marriage. But she did. Uncle James died early. Sis never remarried. As a matter of fact, she never ever had a date. She was a one-man woman. There's no doubt in my mind that Sis is in heaven.

Within a couple of hours from the time Dad called, Sis was packed and at the airport. Dad had a prepaid ticket waiting for her. Nashville to San Francisco. After a three-hour layover, she got on another plane, a little puddle jumper, that made two stops before landing in Crescent City, California, a little coastal town that backs up to thousand-year-old redwood trees in the far northern part of the state, 23 miles from the Oregon border. That's where we lived.

Dad and I met Sis at the terminal. She had been traveling for over 10 hours. Even though she was exhausted and relieved to be there, she began rubbing Dad's back and whispering consoling words to him. Dad bent down and wept into her waiting shoulder. I heard her say to Dad, in that itty-bitty voice of hers, "Don't worry, Billy. We'll put our faith in the Lord. He will help us find little Ricky." I choked up.

My father owned a radio station in town and was the king of the morning slot. Every day, over 60 percent of the region his station covered tuned in to hear what he had on his mind. He always had plenty to say.

The party on the river had been arranged by Ricky. It was a bachelor party for my brother, Gary, who was in the 11th grade and dating a pretty little blond-headed girl with huge blue eyes named Debbie. She came from a deeply religious family, pillars of the community. Debbie was with child. She wasn't quite 16.

It became the talk of the town. Yet another Stamps scandal. My family kept the local newspaper in business up there. Between what Dad had to say on the air, coupled with his nighttime carousing, and my overnight bookings into the Del Norte County Jail, tongues were always wagging. There was a lot of stuff going on under the roof of our home over on Pebble Beach Drive.

Dad decided that Gary should pull out of school and marry Debbie. That's just the way it was back then. If a guy got a girl pregnant, he married her. The plan was that Gary would work for Dad at the radio station and go to night classes to pick up his GED.

What I had to say about the matter fell on deaf ears. I was, at the relief of several, gone from town and in the Marine Corps. At the time of Ricky's disappearance, I was in staging, preparing to ship off to Vietnam. The Red Cross pulled me in and told me what had happened. I was immediately whisked off to the San Francisco International Airport, where Dad and a family friend, Dr. Bert Vipond, picked me up in Bert's little Cessna plane. It was already past 11 at night.

We flew north along the coastline and then over the forests. The wind and the plane's engine drowned out any chance of conversation. You had to yell. About three-quarters of the way home, Bert kept falling asleep. He was the one flying the plane! It was decided that we'd sing to keep the good doctor awake.

All three of us sang "Amazing Grace" over and over. I'll never forget Dad and me and Dr. Vipond, with tears streaming down our faces, singing and crying for the rest of the trip.

My kid brother, Ricky, president of his freshman class, was still out there somewhere. I was sure, with all my Marine Corps training, that I would find him. Wishful thinking. Dad wanted to believe that Ricky was lost in the woods or maybe he had amnesia. Maybe he'd broken his leg. Under the circumstances, that was the best we could hope for.

Georgie Gargaetas was the other boy missing. Not only was he beloved by the Stamps family, but he was Ricky's best friend. Our little town's heart was ripped open. These were two of the finest young men of their generation in the county. They were just 16 years old. The whole town turned out to look for them.

I sat with Dad at a little café, just down from where Ricky fell. I rubbed his shoulders and tried my best to console him. We prayed a lot. Surely God would hear my father's desperate pleadings and Ricky, shaken but alive, would magically show up.

They found Georgie, downriver, a couple of days into the search expedition. It took a full week to find Ricky. His body had traveled several miles down the river to Hiouchi. I went with Dad to Wier's Mortuary to identify Ricky. He was barely recognizable. When we got back into the car, we hugged each other and cried hard. I tried to be strong for Dad, but I just couldn't hold it back. I guess I wasn't as tough as I thought myself to be.

As teenagers will do, Ricky had gotten someone to buy them some booze. It was gonna be a helluva party. Practically everyone in school was invited. It was a great cabin. It sat 200 feet up above the Smith River. Someone turned down the music and yelled out, "Cops!" Everyone scattered into the trees. It was pitch-black dark.

In the confusion and the darkness, Gary stepped back too far and fell a good 50 feet, somehow managing to land on the only rock that jutted out from the bluff. He still deals with pain in his back and the mental scars of that night.

Ricky started down the bluff to get to Gary. It was straight down. Halfway down, he lost his footing and fell over Gary and into the river.

Sis stayed at the house and helped where she could - cooking, doing some laundry, leading in prayer and consoling my family. Just her being there seemed to make a big difference to Dad. Like so many strong, faith-based, Southern women of her time, she stood strong, tight-lipped and kept her emotions from showing. She was calmingly there for us all.

Ricky's funeral was beautiful and terribly sad. I felt like I couldn't breathe. Losing my kid brother tested my faith in the Almighty. I knew that God was with us, but I couldn't understand why he had to take such a great guy at such an early age. Ricky's death, in a weird way, made me fight harder against the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong.

Even though I had a few more days before I was to report back to base, it was decided that I should accompany Sis on the flight back down to San Francisco. Her flight out to the West Coast had been her first time on a plane and had been "a little bumpy." It's a good thing I did fly with her. Pacific Northwest flights aboard small planes are almost always turbulent.

She placed her little hand on the sleeve of my Marine Corps winter green uniform and gripped my arm tight. I patted her hand and told her not to worry. "You have God and a Marine flying with you. No harm will come to us." I really believed that.

Once we landed in San Francisco, I got Sis to her terminal and all checked in. I asked her if she'd like a Coke. She said, "That would be delightful. With a straw, if you please." I brought her back a Coke and a few magazines, and she thanked me. I only had a few minutes that I could spend with her before my flight began boarding.

She told me how proud she was of me and how much she loved me. She told me to please be careful, and she looked at me with tears in her eyes and said, "Call when you can." As I was sprinting toward my gate, those words kept repeating themselves in my head. Either she didn't understand the full depths of war or didn't want to.

Less than three weeks later, I landed in Quang Tri, Vietnam.

More than many times, I've wondered why God didn't take me instead of Ricky. He was so young and had so much goodness in him. I'm looking forward to seeing him again, somewhere down the road. In my prayers, he's my first stop. I'm sure he received a warm reception at the gate.

Fifty-one years later, I still get tears in my eyes and a lump in my throat thinking about him. I felt his presence in Vietnam and have throughout my life. I know my kid brother Ricky's looking out for me.

Bill Stamps' new book, "Miz Lena," is now available in a limited-edition, signed and numbered hardcover. Contact him at bill_stamps@aol.com or through Facebook.