Wednesday's rushed second impeachment of President Donald Trump by a Democratic House prompted us to wonder if the once dark stain on a chief executive's leadership now would become a routine measure taken by an opposing party who doesn't like an action by a president.

We didn't have to wait long to find out.

Late Wednesday, newly elected U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Georgia, said she would file articles of impeachment against President-elect Joe Biden a day after his inauguration next week. The charge, she tweeted, will be abuse of power and is likely to be related to his words as vice president in 2015 when he admitted he urged (and got) Ukraine to fire its prosecutor, Victor Shokin.

Her effort won't go anywhere with a Democratic Congress for two years, but if Republicans retake both houses in 2022, she may not be the only one filing charges. Whether they would involve the political lifer's family business relations with Ukraine and China or actions he takes his first two years in office, of course, remain to be seen.

It's a pity, really. What the Founding Fathers saw as an august, formal and serious action has become a political tool.

Before 1998, though, impeachment only had been visited on the most recent of Tennessee presidents, Democrat Andrew Johnson, whose Civil War political marriage to Republican President Abraham Lincoln didn't seem so promising after Lincoln's assassination and the end of the war. When Johnson sought to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Republicans passed a law - the Tenure of Office Act - that presidents had to seek Senate advice and consent in order to relieve a Cabinet member.

However, the president went about trying to find a new secretary of war as if he hadn't heard about the new law. Republicans countered with impeachment charges, which were adopted by the House. But the Senate did not convict him. The Tenure of Office Act was repealed 20 years after it was signed into law, and judicial experts later said it likely was unconstitutional.

Congresses largely stayed away from impeachment for the next 130 years - with the exception of Watergate charges in 1974 against President Richard Nixon, who resigned before they could be adopted - until Republicans drew up charges in 1998 against President Bill Clinton for lying under oath and obstruction of justice. While Clinton had in fact lied under oath to a grand jury, both charges related to his actions in a sexual harassment suit filed against him. The president, like Johnson, was not convicted in the Senate trial.

The question then, as with the charges against Trump during his term, was whether they amounted to the "high crimes and misdemeanors" status the founders had in mind.

Clearly, the 2019 charges adopted over a telephone conversation with the Ukraine president did not. In the ill-considered impeachment exercise that followed, the president was not convicted in the Senate. Democrats only sought the charges because a more than two-year investigation of Trump and his campaign they were sure would result in his expulsion exonerated him for collusion with Russians in the 2016 election.

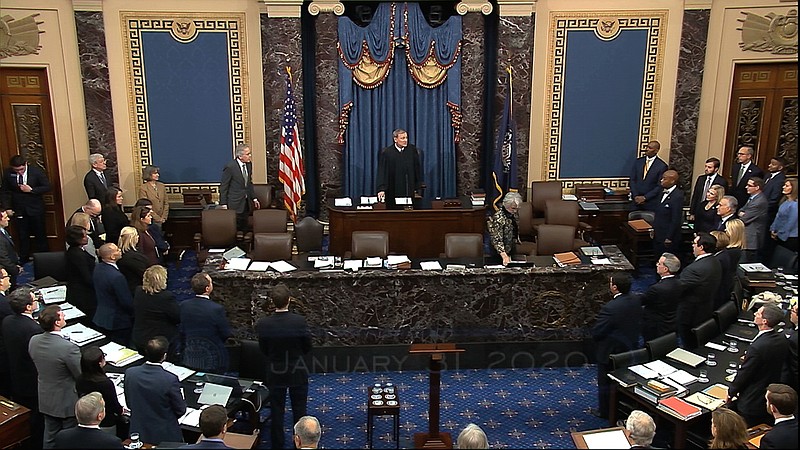

In Wednesday's action, which was taken up over the president's speech to a group of supporters that incited some of them to overrun the Capitol during a joint session of Congress to certify Electoral College votes, only a vote was taken. No evidence was presented, no witnesses were heard, no defense could be mounted. Constitutional experts said - despite the tragedy that resulted - the president could never be convicted for such actions in a court of law.

With Trump in office only a week longer, and a full trial in the Senate not possible before he leaves office, it was an exercise in futility.

That doesn't take away the seriousness of what occurred or Trump's responsibility for his words - he must live with them - but it does weaken any and all future charges of impeachment.

What Republicans in 1868 and 1898 and Democrats in 2019 and 2020 should have considered is a censure, a formal statement of disapproval that is available in the U.S. House and U.S. Senate. It is not mentioned in the Constitution but was adopted as a resolution that is "stronger than a simple rebuke, but not as strong as expulsion."

Of course, a censure, if applied for political reasons, could have become a frequent tool for expressing simple disappointment over policy or deportment, too. But at least it would have saved impeachment for actions like Nixon's during Watergate.

With Wednesday's action, Democrats can smirk and say the work they started in 2015 before Trump ever became president was complete - that he will be leaving office as the only president to date to wear two scarlet I's. With that and $5, they can get a coffee at Starbucks.