"Be ready to walk and crawl, bend and balance for four hours in a dark, damp, but very exhilarating environment."

After that preview of The Caverns' popular Adventure Tour, an armchair adventurer might say "Why?" They might also wonder why watching YouTube through the eyes of a GoPro, while sipping a smoothie, isn't a much better way of viewing the narrow, pebbled crawl spaces; the craggy, claustrophobic ceilings; and the padded elbows inching through mud.

Behind images of the rappelling, the rope-climbing, the trudging, the dark and dirty spaces, caving videos often include music — not the growling guitars one might expect but other-worldly acoustic or classical music. Local caver Kelly Smallwood accompanied one cave journey on her channel with ethereal Native American flute music.

Yet a quick scan of YouTube channels for cavers suggests that the helmet cam might not fully capture the deeper attraction in the sport.

"I find a lot of peace and spirituality in caves," Smallwood said. Sometimes, as the camera follows Smallwood's emergence from a tunnel crawl into a room, she whispers, as if witnessing something sublime.

Contributed photo / Local caver Kelly Smallwood

Contributed photo / Local caver Kelly Smallwood

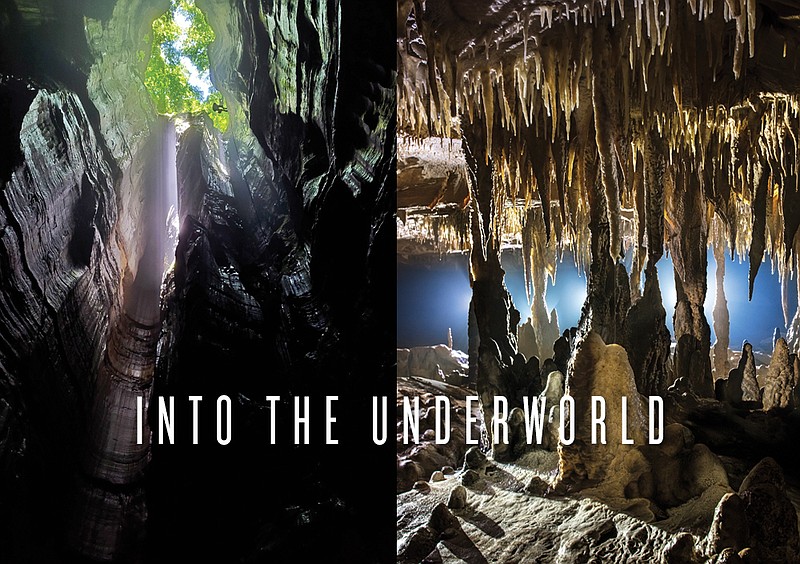

In caves, strange magical cave features, or speleothems, with names like bottle brushes, gypsum needles, soda straws and halite flowers pop like sculptures out of the limestone. Carved over eons by the patient chemistry of caves, their very presence dwarfs the human lifespan. This is the magic of caves.

The Southern Middle Tennessee region is undergirded by limestone, a water-soluble rock that allows caves to form. This topography is often referred to as karst. It took at least 300 million years for water, wending its slightly acidic way through the limestone, ever downward, to sculpt the tunnels, pits and passageways of caves. As cavers descend, they step further back in time into a veritable museum of bygone life — antique coins, petroglyphs, fossils, sharks' teeth.

Smallwood considers herself a "hardcore caver." She's rappelled multi-drop caves 450 feet down and surveyed miles-long caves requiring overnight camping underground. The armchair caver might equate these challenges with an initiation ritual into the club of cave diehards. But perhaps the sport is more analogous to the hero's journey, an odyssey in which the hero leaves familiar surroundings, faces a series of challenges or dangers and grows as a result. The reward is a metaphorical enlightenment or rebirth.

"I believe I am obsessed with caving," Smallwood says. "I want to see as many caves as I can." In Tennessee, state of 10,000 caves, that could take a long time. "They are all so different, but similar — it's really hard to explain."

If anyone can refer to caving as a "hero's journey," it's Smallwood. In 2017, a breast cancer diagnosis upended her life with surgeries and chemo treatments. She continued caving through the whole process.

"One of the things my doctor told me was 'don't just sit on the couch,'" Smallwood told podcaster Matt Pelsor on "The Caving Podcast." "I caved with my [chemo] ports. I actually made a little pillow to go under my ropewalker system [for climbing from a vertical pit]." Smallwood was on chemo for over a year.

The quest to go deeper and see more is probably why cavers acquire new skills (rappelling, rope-rigging and rock climbing) and why cavers with these skills take on "projects" — for example, cave-mapping or cave-surveying.

Smallwood and her husband, fellow-caver Jason Hardy, became well-known cave surveyors when they surveyed the historic Wonder Cave in 2016. They get frequent invitations to explore caves on private property. In fact, most of Tennessee's caves are on private land, and many cave owners allow sport cavers in their caves by permission. This unique arrangement with landowners can be accessed by a simple online permitting process, which includes limits for each cave according to its bio-sensitivity. The process is organized and maintained by the Southeastern Cave Conservancy, a group that also maintains 170+ caves of its own.

Smallwood and Hardy have also been sought out by businesses needing cave surveys. They've surveyed the cave below the Jack Daniels distillery for an expansion project and the caves beneath a proposed power line for the Appalachian Power Company. Jason draws the maps, stopping all along the underground trek to take notes or sketch. While this slows the couple down, Smallwood brings along and mentors less-experienced cavers while Jason is mapping.

"He does such beautiful work," Smallwood said in one of her YouTube videos. "It's almost like artwork."

In 2019, Hardy's cartography was recognized by the National Speleological Society (NSS) for "excellence in cave-related art." In the same year, NSS also recognized the mapping skills of one of the couple's colleagues, caver Ben Miller. The three have surveyed a lot of caves together, according to Smallwood. And one skill Miller has shared is his experience in dye tracing.

Caver Community Service: Tracing the Flow

Contributed photo by Kelly Smallwood / Water-sleuthing — conducting a dye trace to discover where cave water is going — is often a team effort. Here, team Smallwood and Hardy are conducting a trace.

Contributed photo by Kelly Smallwood / Water-sleuthing — conducting a dye trace to discover where cave water is going — is often a team effort. Here, team Smallwood and Hardy are conducting a trace.

A hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, Miller tracks the flow of water from surface streams to where the water sinks and travels through caves. His job is to discover where water eventually flows out. Water can flow very unpredictably through caves and wind up in unexpected streams, basins or springs. Those surprises keep Miller hooked on cave hydrology.

To track the water's path, he will pour a non-toxic dye into the waterways on the surface and then track the water on its path through the cave, a process called dye tracing. As it travels, the color disperses until it is undetectable by sight, so Miller and his teams must navigate the cave, locate the waterways throughout and place detectors (charcoal packets) in the ones that flow. Then periodically, the team revisits each location to collect and change out the packets. One of Miller's more challenging dye traces involved water streaming through a long "horizontal" cave in the Ozarks with 20 miles of passages.

"Some of these packets were so deep into the cave that they could not be reached in a day," Miller said. "[Retrieving them] required camping underground."

Long caves like that are rare in Tennessee, Smallwood said. "We get a lot of short caves and pits, but not as many mile-plus-long caves." So she was excited when she and Jason began surveying a cave with a listed 4,500-foot length.

"We felt like we could squeeze at least a mile out of it," Smallwood recalled. After many trips into the cave, they found the caver's pot of gold: a blowing hole.

"I heard a strange noise. It was a weird noise, not quite like water rushing or air," Smallwood remembers. "As I was talking, I literally saw my breath blow sideways." She followed the sound to "a fist-sized hole." "It was blowing a massive amount of air through a very small space," she said.

The rushing air suggested that there was a lot more space on the other side. Smallwood and team dug their way through about 11 feet of mud and emerged into a "walking borehole passage," as the rushing air had predicted. In that memorable survey, Smallwood and her team went on to discover a large room, a 93-foot waterfall and 8,000 more feet of passage.

"Over the course of the project," Smallwood added, "we taught 10 cavers how to survey."

Many of us stay above ground, oblivious to the world of rooms, pits and passages running beneath us. And yet cavers' voluntary projects serve us in many ways. The water that floods our homes when pressure drives it up through the caves, the water that feeds our wells or springs, is not easy to follow through a cave, even when the cave is easily navigable. Often only a skilled caver can do it.

Miller and his teams have conducted surveys and dye traces all over the Cumberland Plateau, providing puzzle pieces for community planning, ecological research and land management. A typical project for Miller is "related to either springs used by unique biota or at springs used as drinking-water sources by communities," Miller said. He recently traced water flows for the towns of Jasper and Cowan, Tennessee, two communities highly dependent on spring water.

About the same time, a family that had a quarry move into their neighborhood called on Smallwood for help. As if periodic, earth-shuddering blasts from quarry activities weren't enough, the family and their neighbors began to worry about runoff from the quarry.

"There are over 6 miles of cave passage where the water could be affected by the quarry runoff," Smallwood reported from her survey. "Many of the landowners in this area are also on well water, so they were concerned with the possibility of contaminants."

It was Smallwood's first time supervising a dye trace, but she and her team found one tracer showing up in a neighbor's toilet. Smallwood is hoping to make a film about the whole process.

"The data now exists to hopefully prevent this from happening again in this area," Smallwood said. "Many counties in Tennessee are poor and are often taken advantage of by corporations, especially the ones that destroy the environment."

It often falls to volunteer sport cavers like Smallwood to get a better understanding of what lies beneath a community's feet. It still happens that neither science nor common sense fully understand what water is up to.

"We've found in multiple studies that karst groundwater can travel below rivers to reach a spring," Miller said. "Karst groundwater often doesn't follow the topography."

Someone has to track it. Fortunately, some "obsessed" underground explorers who just love these gritty but surprising places are on the case.

(Sources in addition to interviews: caves.org; saveyourcaves.org; sewaneemessenger.com; nashvillescene.com; tagcaver.wixsite.com)

SIDEBAR:

To get into caving...

If you've never gone caving and want to try it, the Chattanooga area is a mecca for commercial "adventure" or "wild" cave tours. These rugged but guided tours at The Caverns, Raccoon Mountain Caverns and Cumberland Caverns run 2 – 4 hours and provide a good sampler of the environments and challenges typical in caves.

If the adventure appeals, its tour guide can usually help connect explorers with a local caving group. According to experienced cavers, hooking up with a local grotto (caving club) is the best way to begin caving.

Though cavers can be secretive about caves, they're also friendly and willing to share knowledge and experience with new cavers. Initiation into the club is less about gear or athletic prowess and more about understanding the vulnerability of caves, which are eco-sensitive places. Not only are they like museums, full of ancient, fragile structures, but they're home to unique, vulnerable animal species. The caving code of ethics is something akin to "leave no trace."

Besides the fact that caves can be dangerous and group exploration offers safety, starting out among experienced cavers offers advantages like acquiring cave skills, getting to know local caves and meeting like-minded people. Additionally, the experienced caver on an expedition has probably reserved the cave permit, knows the cave and has a relationship with the cave owner.

Local grottos are listed on the National Speleological Society's website by state — Tennessee has 10. The Sewanee Mountain grotto, the Chattanooga grotto (which meets monthly) and even the Nashville grotto hold events in the Chattanooga area. They're all likely to have a presence at the three-day Cave Fest event, October 6 – 8 at The Caverns.