For those of you spending a good amount of time outdoors, you've likely shared space with some interesting creatures. You may have gotten up close and personal — whether by design or misfortune — with critters ranging from raccoons to rattlesnakes, bees to bears. For better or worse, love or hate, these animals are floating through the waters we swim in, slithering through our forests, fluttering on the breeze and circling our heads in the caves we spelunk.

But if we're going to peacefully coexist with them, we may want to understand what makes them tick. Or sting. Or hang upside down. Or echolocate.

Here's a look at two of the most unique, fascinating and misunderstood animals out there: jellyfish and bats.

ARMED AND DANGEROUS

A look at the soft, venomous, tentacled wonders that are jellyfish

Jellyfish are like campfires, lightning, poison ivy and certain people — great to look at, but much better kept at a distance. These squishy creatures are graceful and rhythmic and flowy; their elegant, pulsing movements are mesmerizing to watch. But if you get too close, their charm very quickly wears off. They inject venom into your skin, and it smarts — a lot. Then the fun abruptly ends. Jellyfish are far less beautiful when their tentacles are wrapped around your leg.

One person who risks stings and tentacle abuse every single day is Rachel Thayer, jellyfish whisperer, master of Medusozoa, cnidarian wrangler. Her official title is Assistant Curator of Fishes at the Tennessee Aquarium, and she has thousands of gelatinous buddies under her care.

Thayer has worked with a variety of aquatic and land-based beasties. She started at the aquarium as an aquarist, or a person who is in charge of aquarium exhibits. When a position opened up as a governess of jellyfish, she decided to give it a try. "I was like, jellies are interesting and weird. They're so intriguing," she says.

Staff photo by Olivia Ross / Rachel Thayer, Assistant Curator of Fishes, poses for a photo in front of the Pacific sea nettles at the Tennessee Aquarium.

Staff photo by Olivia Ross / Rachel Thayer, Assistant Curator of Fishes, poses for a photo in front of the Pacific sea nettles at the Tennessee Aquarium.

A Sting Operation

That was seven years ago, and Thayer now intends to work with jellyfish indefinitely. She took to them like a jellyfish to water. "They've definitely been something that I have cultured up a passion for in a lot of different ways," she says. "Jellies have definitely hooked me."

"Hooked" is an interesting choice of words. Perhaps "stabbed" or "harpooned" would be more appropriate, considering how the process of being stung by a jellyfish actually works. "Their stinging cells look a lot like a harpoon that's wound up. It has a little hair trigger on the outside, so that if you brush against that hair trigger, this harpoon shoots out" (and straight through your skin!), Thayer explains. "That's the fastest accelerating structure in the animal kingdom that we know of so far. And that's how they sting you."

Plenty of Jellyfish in the Sea

Thayer notes that not everyone reacts the same to jellyfish stings. As with snakebites, some people are more susceptible to jellyfish venom than others and will therefore have more or less of a reaction. And naturally, how painful a jellyfish sting is also depends on the jellyfish. There are at least 4,000 different known species of jellyfish — only 70 of which cause harm to humans. That said, some 150 million unfortunate swimmers come in contact with jellyfish every year, and approximately 100 of them won't live to talk about it.

The species of boxy, cubic jellyfish aptly named box jellies are usually the deadliest. Among them, the Irukandji — found primarily near Australia — is perhaps the most dreaded. At just over a half of a cubic inch, this tiny tater tot of doom has a small size but a mighty big sting — enough to strike fear into the hearts of beachgoers and swimmers everywhere. And enough to kill. "Their venom is highly toxic with a very, very painful sting," Thayer says. But, she adds, jellyfish stings aren't necessarily death sentences, and people do survive even the toxic tentacles of the box jellies.

What to do When Urine Pain

Thayer would very much like to debunk a rather mainstream myth — no, you should never pee on a jellyfish sting. She assures us that this is nothing more than an urban legend, based on the incorrect assumption that ammonia in urine will fight the venom, and popularized by an episode of "Friends" (the one where Chandler pees on Monica after she gets stung). "Mammals don't excrete ammonia; we excrete a different product called urea," she clarifies, leaving absolutely no advantage to going number one on what a jellyfish has done.

So having someone pee on you post-stinging will merely cause a rather awkward, unpleasant and potentially unsanitary situation that might only prolong your pain. And you need that about as much as a jellyfish needs a bicycle.

On the other hand, Thayer insists that what will help is treating the area with vinegar and hot water — "as hot as you can comfortably stand it," for 30 seconds to a minute.

The Jelly of the Beast

Photos by Olivia Ross / Pacific sea nettles are on display at the Tennessee Aquarium.

Photos by Olivia Ross / Pacific sea nettles are on display at the Tennessee Aquarium.

Jellyfish are aquatic beings without bones nor brains. The viscous, jelly-like substance they're made of is known as mesoglea, which is "mostly water and a little bit of protein," Thayer explains. She likens it to slime or runny Jell-O. "Basically, it's just like if you made Jell-O that didn't really set right," she says — which would make jellyfish a swimming Jell-O failure.

Their highly unique, unusual and complicated life cycle is one of Thayer's favorite things about them. "They're the only ones doing it that way," she says. Jellies go through several stages, including an egg, planula (larva), polyp and adult (medusa) stage. Some adult jellyfish can live for 5-10 years, and scientists believe that jellyfish polyps are virtually immortal.

Although it's not been proven, Thayer and many others assume that most jellyfish don't seek people out to sting them. They're just out there minding their own business — swimming, looking for prey, reproducing and trying to fend off predators when needed. "That's their whole game: find food, make more jellies," Thayer says.

Jellyfish go with the flow. "They're not strong swimmers; they're kind of at the mercy of the current," she adds, which only leads to more unintentional collisions. And when they cross paths with humans sharing their waters, it can be a rather excruciating reunion.

Many Moons

Thayer prefers to raise her own jellyfish rather than cultivating them from the oceans or rivers. (Yes, rivers. Freshwater jellyfish such as the peach blossom jelly live in our very own Tennessee River, she says. Luckily, those guys won't hurt us.)

At the aquarium, she's currently raising several different varieties of jellyfish, including both Pacific and Atlantic sea nettles, moon jellies by the bundle, upside-down jellyfish and lion's mane:

- Bats don't have a corner on the upside-down market. Upside-down jellyfish spend most of their lives inverted because it's easier for them to feed that way.

- The lion's mane jellyfish, which is one of the largest to glide through the oceans, ranges in size from a foot and a half to 6.5 feet — though the largest on record was 120 feet long. That's half the width of a 747 wingspan and two and a half times the length of a semi-truck! Lion's mane jellies also have up to 1,200 long, flowing tentacles.

- Moon jellies — of which Thayer has heaps — are the Golden Retrievers of the jellyfish world. They're cute, lovable and virtually harmless. This is one jellyfish species that won't sting you — their stingers are simply too weak. It's a little bit like trying to ward off a bear with a toothpick. "They're probably trying to sting you, but it doesn't get through human skin, so we don't feel it," Thayer says.

Krill Waters Run Deep

Thayer confesses that jellyfish are very high-maintenance animals. Their upkeep involves a constant rotation of cleaning and feeding, including removing slime from the aquarium tanks and making two different flavors of fish smoothies to feed to her doughy dependents. "I've done what we call krill shakes – krill is that little shrimp-like animal that big whales eat. It comes in frozen, and we'll blend it up and feed that to the jellyfish, and they love it. I've done that with clams as well," she says. "I wouldn't necessarily recommend it for anyone else, but it seems to be very nutritious." (No, it's probably never going to make the menu at Sonic.)

"I think being a jellyfish aquarist can be really, really weird," Thayer admits. "I'm always the one downstairs putting weird food into a blender, where every other aquarist is just politely cutting their seafood and scattering it into their exhibits."

Feeding the sea nettles is even more labor-intensive, since these cushiony cannibals have to eat other jellyfish. Thayer is able to break off a part of one type of the moon jelly's tentacles, known as oral arms, to give to the sea nettles. This way, everyone gets to eat, and the moon jelly remains unharmed and can in fact regenerate what is removed for the nettles' lunch. You could say that the moon jellies would give their right arm to feed their hungry comrades.

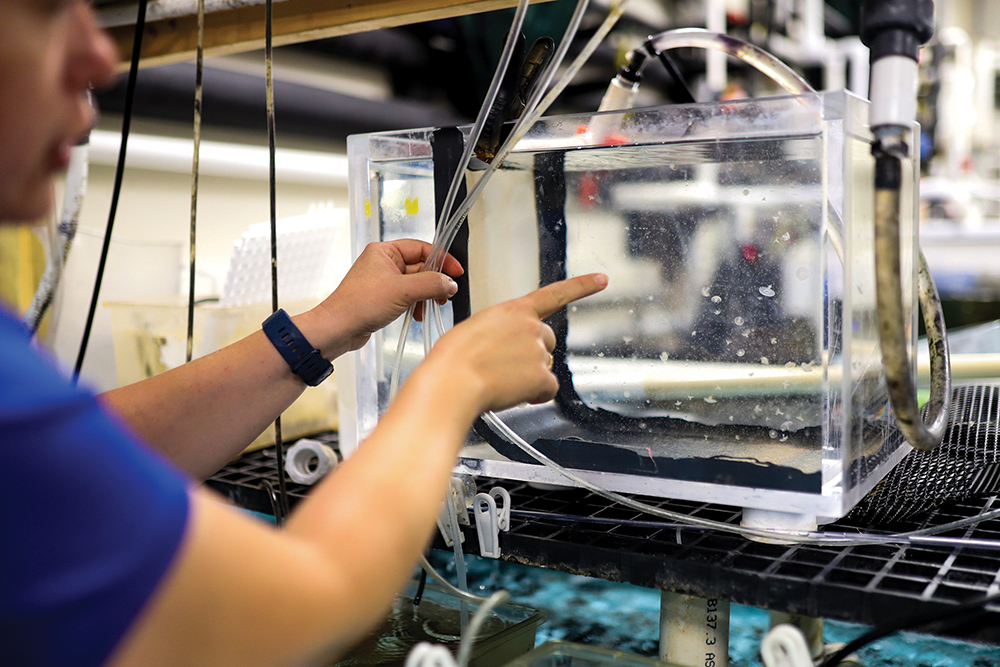

Staff photo by Olivia Ross / Thayer points to young moon jellies in the Quarantine Room at the Tennessee Aquarium.

Staff photo by Olivia Ross / Thayer points to young moon jellies in the Quarantine Room at the Tennessee Aquarium.

Jellyfishing for Compliments

Thayer has virtually nothing but good things to say about jellyfish. She considers them tranquil and alluring, with an impressive variety of "colors and patterns and different lengths of tentacles." "Yes, they sting. But they're also really beautiful. They're also food for animals you might really like, like sea turtles. That's a big part of a sea turtle's diet," she says. Not to mention, research is being done on using these mushy do-gooders for pain medicine, since many species have neurotoxins in their venom.

"So you know there's a place for them here, and they're probably not going anywhere anytime soon. It's good to learn to respect them and embrace them from a safe distance."

Love them, but keep them at tentacle's length.

Jellyfish are so cool that it makes us a little jelly! Here are some fun facts about these interesting creatures.

- Jellyfish have been around since the beginning of time — some 500 million years.

- They have a nervous system but no brain.

- Their tentacles are arms, anatomically speaking. They're mainly intended to keep prey within arm's reach and to strong-arm predators.

- Jellyfish are made out of a slimy, Jell-O-like substance known as mesoglea.

- There are at least 4,000 species of jellyfish.

- As much as 400,000 tons (900 million pounds) of jellyfish are fished in Asian waters for human consumption (peanut butter and jellyfish, anyone?). That's more than the weight of the Empire State Building in jellies!

- Jellyfish polyps may possibly live forever.

(Sources in addition to Rachel Thayer: ocean.si.edu; themeasureofthings.com; oceana. org; americanoceans.org; worldatlas.com)

AT THE DROP OF A BAT

There are bats in the cave. Hanging around; plunging through the darkness. Many people dread them, but bats are actually helpful and intriguing animals.

Staff file photo / Bats fill the sky outside of Nickajack Cave.

Staff file photo / Bats fill the sky outside of Nickajack Cave.

Any summer evening around dusk, you can look across the cove from Highway 156 and see a huddle of kayaks and canoes treading water before Nickajack Cave. They're waiting, like acolytes at the gateway of an ancient temple, for the nightly twilight emergence of gray bats.

As thousands upon thousands of bats stream out along the tree line in an urgent window of time between their predators' change of shifts — hawk by day and owl by night — it's an eerily quiet event. But a frenzy of bat dives and swoops, of tracking, snagging and consuming up to 3,000 flying insects each, will soon follow. The mostly mother bats have hungry mouths to feed back in the cave.

These large groups of nursing gray bat females favor only a handful of Tennessee caves, to which they are quite loyal. They return year after year to hang upside down from the cave's nicely vaulted dome in its ideal warmth and humidity.

Gray bats have long been on the endangered species list due to habitat loss, cave disruption and other human activities. In fact, these activities have led to a decline across all bat populations.

But being listed as endangered, the gray bat receives a lot of protection (such as the metal gate barring entrance to Nickajack Cave) and continual population surveys. Tennessee wrapped up its 2023 count of the bats at Nickajack Cave, a "priority cave," over the summer, according to Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) biologist Chris Simpson. Simpson pioneered TWRA's use of thermal cameras for counting the bats as they emerge, and those 2009 studies now serve as a baseline.

"The [2023] numbers are not in yet," Simpson said, "but we had greater than 100,000 gray bats that emerged."

In addition to gray bats, Tennessee has 15 other bat species, each with its own lifestyle. One species might be living in small groups in a tree hollow, while many lone individuals of another species might be tucked into small crevices in a boulder. In fact, bats may be quietly roosting, unseen, all around us. At the Raccoon Mountain Caverns, any cave tour guide can point out a resident colony of cave-loving tricolored bats. The largest Tennessee bat, the hoary bat, could be hanging from a tree branch 15 feet above our heads. And colonies of little brown bats may live quietly in a neighbor's attic — until the homeowner decides to repair the roof.

Staff file photo / TWRA and TVA officials exit Nickajack Cave after setting up an infrared camera to track the gray bat population.

Staff file photo / TWRA and TVA officials exit Nickajack Cave after setting up an infrared camera to track the gray bat population.

According to Alyssa Bennett, who coordinates Vermont's citizen bat volunteers, the little brown bat seems to prefer human structures. This could be its curse or its cure, depending on how the humans respond. Bennett works to bring homeowners into the cure camp. She encourages them to "evict" bat squatters from their homes using one-way doors and to install state-provided bat houses elsewhere on their property. With bats safely away from houses, fascinated homeowners often become part of the monitoring program — a win-win for humans and bats.

Lucky for the gray bat, it is not particularly vulnerable to White-Nose Syndrome, a fungal disease from Europe that hit U.S. shores around 2006 and began a rampage across the country. The little brown bat was all but wiped out by the disease, along with the tricolored bat. And as many as 99% of northern long-eared bats (listed as endangered this past March) reportedly succumbed to White-Nose Syndrome. Tennessee is home to all three of these bat species.

The good news is that aggressive research is paying off with several promising approaches on the horizon. For example, a vaccine approach targeting the disease may begin ramping up this year, which makes continued monitoring of bat populations very important.

The 2023 bat surveys are expected to contribute to a new era of research. New data tools have allowed the latest reports to pool the jumble of snapshots — surveys involving 30 bat species, 700+ projects, 49 states — into one national picture for the first time.

Conservationists already seem hopeful that the 2023 picture will be good news for bats.

"We're starting to see a rebound in the little brown bat," said Owen Boyle of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, though he cautioned, "but it's still only 40-45% [up from a mere 10%] of the pre-White-Nose population."

Photo by David Stephenson/Lexington Herald-Leader/MCT / Biologist Jeff Hawkins holds a gray bat that had been caught in a harp trap at a survey site near Nicholasville, Kentucky.

Photo by David Stephenson/Lexington Herald-Leader/MCT / Biologist Jeff Hawkins holds a gray bat that had been caught in a harp trap at a survey site near Nicholasville, Kentucky.

Many people, unnerved by bats, might wonder why so much effort goes into conserving them. Bats do have a grim reputation. But it's often based on exaggerated stories that focus on a few species (of the over 1,460) or rare occurrences of rabies.

On the other hand, farmers and natural gardeners know that bats are the only appreciable predators of night-flying garden pests. A bat can consume as many as a thousand insects per hour, devouring a third to two thirds of its body weight in insects each night. Bats graciously eat mosquitoes — reason enough to want them around.

The city of Austin, Texas, once annoyed by the million-plus bats under its Congress Avenue Bridge, soon learned that the bats were saving local farmers huge crop-dusting expenses. On a nightly forage, these Mexican free-tailed bats reportedly traveled as far as 100 miles, well into farmland, resulting in the consumption of up to 30,000 pounds (15 tons) of insects each night.

Come fall, the gray bats of Nickajack Cave will mate, and just like Austin's Mexican free-tailed bats, they'll leave in October for their winter homes. As with most bats, the gray bat females will hold sperm and delay fertilizing their eggs until late winter. In this way, they ensure that the birth of their young coincides with their return to the humid, vaulted dome of Nickajack Cave next summer.

(Sources in addition to interviews: fs.usda.gov; digital.batcon.org; tpwd.texas.gov; defenders.org; nabatmonitoring.org; fws.gov; usgs.gov)

Photo by David Stephenson/Lexington Herald-Leader/MCT / A colony of gray bats wake up from their day's sleep and prepare to emerge from a crevice under a bridge near Nicholasville, Kentucky.

Photo by David Stephenson/Lexington Herald-Leader/MCT / A colony of gray bats wake up from their day's sleep and prepare to emerge from a crevice under a bridge near Nicholasville, Kentucky.

Bat facts

1. The Mexican free-tailed bat reigns as the fastest mammal. It can fly in bursts of up to 100 mph, topping the land speed of the cheetah.

2. Bats are attracted to wind turbines, now a leading cause of bat mortality. What's the attraction? Researchers are still trying to find out.

3. The wingspan of the largest bat, the Philippines' giant golden-crowned flying fox, averages over 5 feet — larger than a hawk's. Fortunately, it eats fruit.

4. Every bat has a unique "contact" call. Mother and baby bat find each other, even among 20 million bats, by recognizing each other's calls.

5. Bats are not blind; they see differently. For example, they may see less color than humans. But on an evening hunt, when adaptations for low light make more sense than color vision, bats might see better than humans. When on the hunt, bats (or at least 70% of bats) send out an inaudible, high-frequency spray of pings to locate prey — a kind of aerial sonar or echolocation. Between sight and sonar, these nimble flyers can nail an insect the width of a human hair in mid-air.

6. Some bat species eat lizards, frogs, birds and other bats; some eat scorpions; some eat flower nectar. (Pallid bats eat both scorpions and nectar.)

7. Fruit- and flower-eaters can be important to agriculture as seed-spreaders and pollinators.

8. Of vampire bats, there are only three species — all south of the U.S. border. However, biologist Nancy Simmons says that climate change will edge the Mexican vampire bat into Texas. They don't suck blood; they lap it (after making a cut with their teeth). Their primary targets are sleeping cows, pigs and chickens — not humans.

9. Bats sleep hanging from their feet because, Simmons says, in their evolutionary tree-dwelling days, they clung to tree trunks facing downward, letting gravity boost their leap towards prey. Since acquiring wings, bats' feet clench at rest, and their ankle bones lock. Valves in their arteries keep blood from rushing to their heads. All this helps them drop head-first into gravity's arms for lift and easy takeoff.

10. Seven bat species sleep curled up in leaves.

(Sources: batcon.org; wtamu.edu; mos.org; latrobe.edu.au; ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Chaz Johnston contributed to this story.