Before the digital age brought us the ability to play any music we could imagine on demand, music-lovers relied on live people playing instruments to provide the soundtracks to their lives. Starting in the 18th century, pianos became the instrument of choice - at least for royalty and the aristocracy, and then later the middle class. During the Victorian era, this new social stratum purchased millions of pianos and less-expensive pump organs. Symbols of status and a source of entertainment, they were a staple in many homes up through the Great Depression and beyond, though to a lesser extent.

As recorded music came on the scene with the introduction of the automated player piano in 1900, followed by the phonograph and then the radio in the 1930s, amateur piano players slowly dwindled in number. In the late 2000s, the piano industry took a huge hit during the Great Recession, when 168 piano dealers nationwide went out of business, says Buddy Shirk, store manager and director of institutional sales and concert artists for Summitt Pianos, a century-old local piano and organ dealer. Even after the economy improved, "nothing returned to normal," he says.

Since the advent of rock 'n' roll, the guitar has become the entry-level instrument of choice; and less expensive, portable electronic keyboards are now more popular for those who do choose to play piano, says William Barger of Barger & Nix Organs. He's been building, servicing and tuning organs since 1960. In his first decade of business, he rebuilt heirloom pianos for some of the city's wealthier residents, but not many people are putting money into older pianos these days, he says, because there's little chance of getting it back out. "Eighty-five to 90 percent of pianos for sale are not worthy of the expenditure of being long-term instruments," says Barger, for whom universities, churches and schools are now the majority of his clients.

The piano's cultural role has changed, becoming a perch for picture frames relegated to a seldom-visited corner of the home. But there are still people carving out a place in their homes and their lives for the instruments treasured and passed down by the generations that came before, though largely for sentimental reasons.

Such is the case with Charley Spencer's heirloom Victorian pump organ, built in Boston by Smith American, probably around 1880, he estimates. His great-grandfather, who ran a boarding house in Buckingham, Virginia, just outside Appomattox, likely purchased the organ in the early 1900s from a traveling salesman to entertain guests in the parlor, Spencer says. During that time period, pump organs were more common to have in the home than pianos due to the cost, around $200 for a pump organ as opposed to around $1,500 for pianos, according to Spencer's research.

The boarding house then became Spencer's grandmother's home, where the organ sat in the same spot for 60-70 years. After her death, it was passed down to Spencer's father and, when Spencer's mother passed, it came into his possession "because, who wants an organ?" he says.Spencer says he and his wife are generally more willing than their siblings to take on things that belonged to their families. Their 1920s-era home in Signal Mountain's Old Town is spacious enough to accommodate large antiques, he adds, pointing to a wooden cabinet that's been in the family for several generations and which spans the length of an entire wall. Spencer says he is the keeper of family heirlooms aside from just those that require a great deal of space - photos, letters, art projects, toys; anything with history and a story behind it, which he is always happy to tell.

While beautiful objects, Victorian pump organs like Spencer's have little market value. His organ is functional, though he doesn't play. He considered having it restored, but decided against it since he assumed it would be labor intensive and expensive.

"In our house, growing up, the piano was kind of a centerpiece," says Spencer who, along with his three brothers, learned to play as a child.

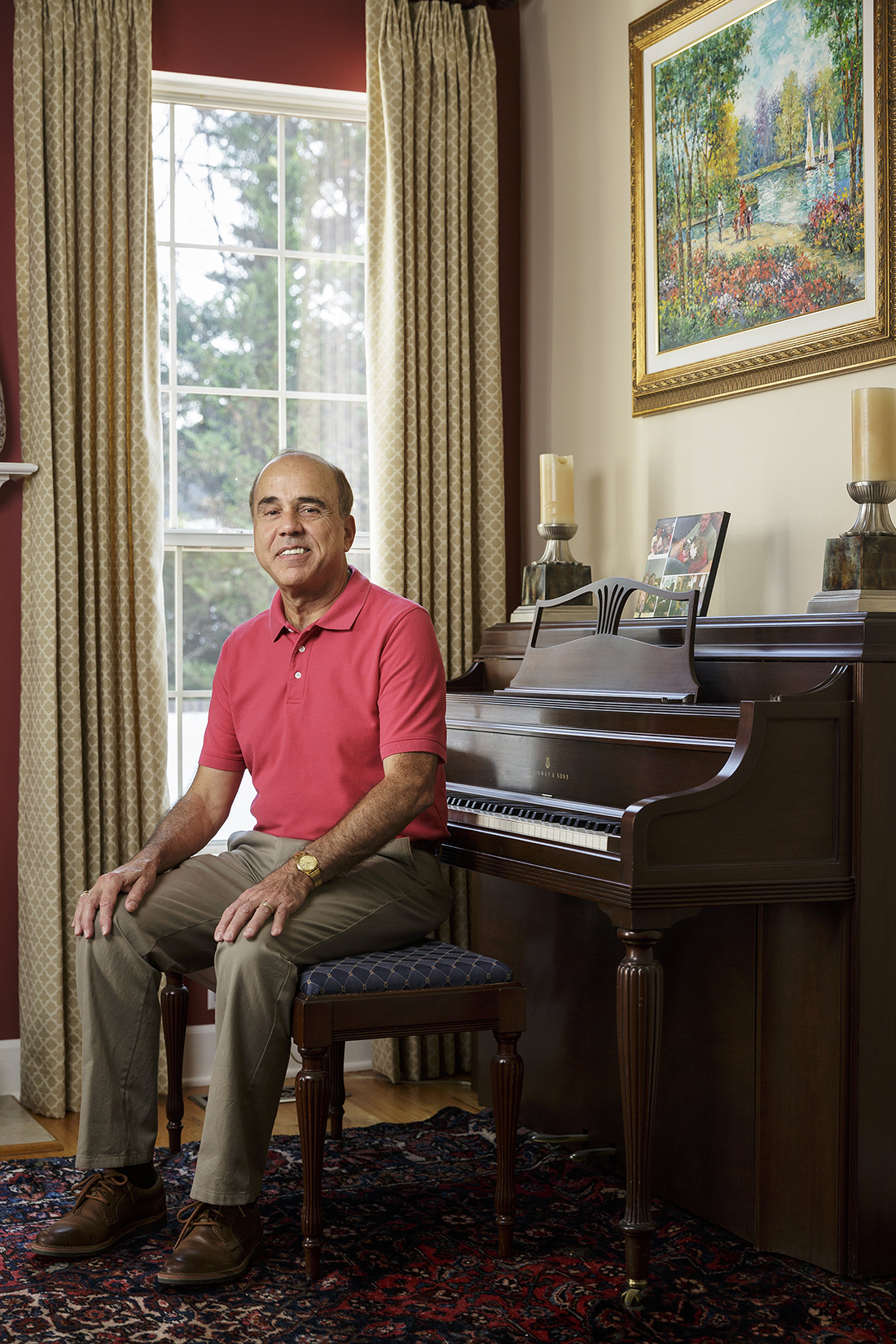

The piano also played a central role in Dick Gordon's home while he was growing up. Three families lived in his Boston home, with Gordon living on the third floor, his godparents on the second and his aunt and grandfather on the first.

His aunt played the piano, which sat on the first floor - that is, until 1960, when 10-year-old Dick, who was taking lessons at the time, took the piano apart. One of the keys wasn't working, he says, so he went down to the cellar to get some tools belonging to his grandfather, a carpenter. "I was trying to fix it," he explains, though by the time he'd finished, 10 of the strings were broken and the piano was beyond repair. Needless to say, he was never permitted to touch its replacement, a Steinway console crafted from mahogany, purchased in 1965. "She held a grudge," Gordon says of his aunt. Nevertheless, he continued to take lessons for years, even though he was unable to practice at home.

When his aunt passed away in 2011, at age 104, Gordon hired Summitt Pianos to arrange for the Steinway to be transported from Boston to Chattanooga, where Gordon, a former federal judge, had moved in 1986. The piano is now in his East Brainerd home, where he allows his grandchildren, ages 2 and 4, to pound on the keys. He believes one of them may actually have some talent. Gordon doesn't say the same of himself. "The best thing about the way I play is the way I dress," he says. When he hosts parties, he says it's not uncommon for guests to tickle the ivories of his family heirloom.

Among Gordon's piano-playing guests is Shirk who, in addition to his 43 years selling pianos, also has 36 years of professional music experience as a former church organist, longtime entertainer and studio musician. Unlike many older pianos, Shirk says Gordon's piano is more valuable today than when it was purchased: $3,000-$4,000 now, Shirk estimates, up from the original price of $700-$800. Steinway pianos are relatively rare, with around 700,000 produced since 1856, compared to the around 6 million produced by Yamaha since the 1950s, Shirk explains.

Gordon is lucky - many people who inherit pianos are surprised to find they aren't worth the cost to move them, Shirk says. In those situations, people sometimes repurpose them as furniture such as bars, bookcases and headboards. Local artist Rondell Crier created works of art for Jazzanooga using old piano parts, says Shirk. He also knows of a woman who crafts birdhouses from piano keys. But Shirk still believes the instrument holds cultural significance. "Every home needs a piano," he says. "Every life needs music."