Researchers from Southern Adventist University are working with the Chattanooga Police Department to help provide cadets with a better understanding of the economic and societal barriers experienced by those living at or below the poverty line.

Since 2015, a team from the university's School of Social Work has been working with the CPD to address implicit biases officers may hold toward various minority groups, including those in low-income brackets.

Thanks to a $16,000 grant provided by California faith based foundation Versacare, the team has now moved into its implementation phase, which will give up-and-coming officers soft-skills training through the Community Action Poverty Simulation.

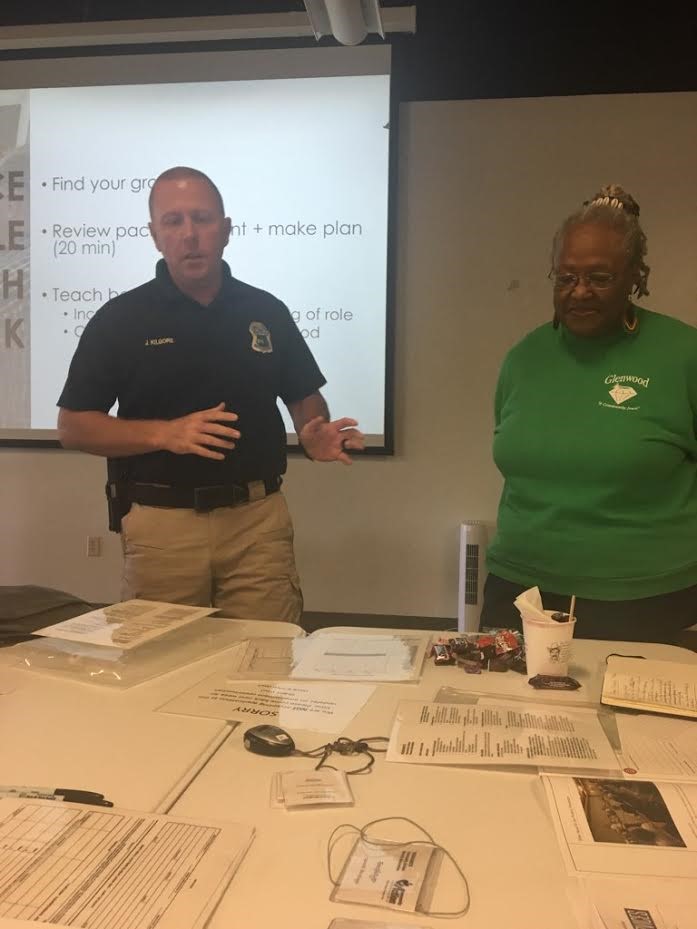

Everlena Holmes and Sgt. Justin Kilgore partner together during the train-the-trainer portion of the poverty simulation, which helped interested parties become certified facilitators for future simulations. The facilitators will partner with each other and SAU to conduct simulations for any agency, business, place of worship or school that would like to host a simulation at its site. (Contributed photo)

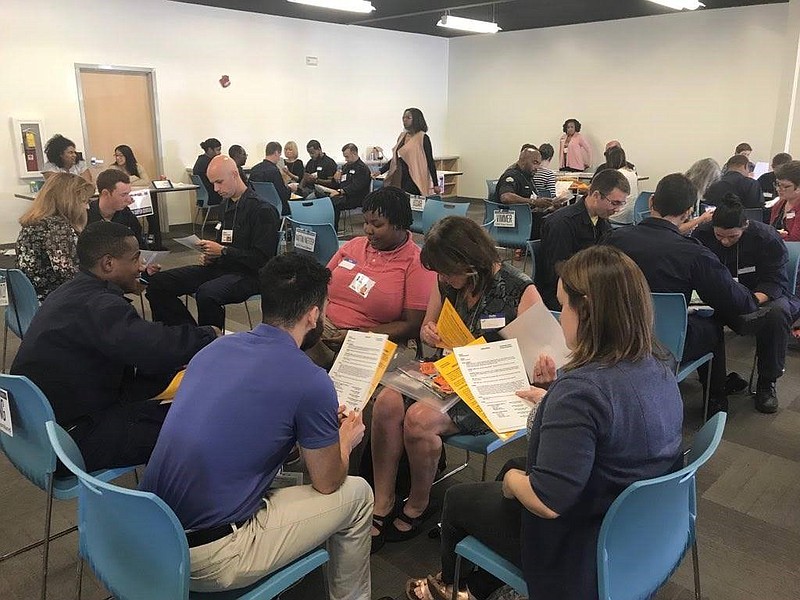

Everlena Holmes and Sgt. Justin Kilgore partner together during the train-the-trainer portion of the poverty simulation, which helped interested parties become certified facilitators for future simulations. The facilitators will partner with each other and SAU to conduct simulations for any agency, business, place of worship or school that would like to host a simulation at its site. (Contributed photo)Created by the Community Action Network, based in Missouri, the simulation takes place in a large room, with stations set up to represent a bank, child care facility, grocery store and other establishments that are daily necessities. Each person is then assigned a role, whether it be working at one of the stations or living as a poverty-stricken family.

Armed with a finite budget, bills to pay, mouths to feed, and other daily stresses gleaned from actual clients of the Missouri Community Action Network, the participants are challenged to do their best to make ends meet over the course of three hours, with each hour representing a month.

CPD conducted the first poverty simulation in October with 30 cadets as well as interested people from the community, said Kristie Wilder, dean of SAU's School of Social Work. For those who had never encountered poverty, the simulation was a rude awakening, Wilder said - especially if they returned from one of the stations to find the chair signifying their home turned upside down with a sign that read "Evicted."

"You see people literally choosing to steal to survive because they have no other option; then they might get arrested and not be able to bond out," said Wilder. "It demystifies those people. It's removing the 'othering' issue and opens a door to get to know those people."

CPD Assistant Chief Glenn Scruggs, who grew up in conditions similar to those simulated, sat in on the training and said he could see "a lot of light bulbs coming on" for some of the cadets as they went through the exercise in empathy. He recalled the frustration expressed by one cadet playing a single mother who couldn't figure out how to get her lights turned back on or file an insurance claim because she couldn't pay the fee for transportation to take her and her two "children" to the necessary stations.

"She was stumped that people had to go through all these hoops to get to that," Scruggs said.

Though Scruggs admitted that three hours might not be enough to provide an overall understanding of the complexities those in poverty face, he said he believes the simulation is valuable because it serves as a way to start a larger conversation and reminds trainees that they still have more to learn.

Caroline Huffaker, CPD victim services coordinator, said the October training session also shed light on ways she could improve operations for the victims with whom she works. Through the exercise, she saw how financially taxing it could be for someone living in the simulated conditions to make multiple trips to the police department for follow-up interviews, to file a victim compensation application or to pick up their property - especially if they don't have paid leave time from work.

"It helps me think through how I can help them engage with our department in a way that also is efficient and economically sound for their living situation," she said.

The simulation will continue to be a regular staple of the 22-week training process for future CPD cadets. Taking place around week six of the academy, it will enable the cadets to refer back to the lessons gleaned from the exercise throughout the duration of their academy experience, said Huffaker.

In conjunction with the simulations, researchers from SAU will collect before-and-after data on the police cadets' attitudes on poverty and race.

Wilder said the research would not have been possible without former CPD police chief Fred Fletcher, who supported the initial research grant that gave birth to the partnership in 2015. She also applauded current Chief David Roddy, whom she said has been just as supportive of the work and receptive to the research presented.

"This speaks volumes to the leadership at Chattanooga Police Department," Wilder said. "We could do all the research in the world; they don't have to implement it."

The International Association of Chiefs of Police, which provided SAU with the initial research grant, has also indicated its interest in using the university and police department's partnership as a best practice model, said Wilder. Working with IACP, the local researchers would produce a webinar showcasing their collaboration in the hopes of inspiring more police departments to engage in similar undertakings.

Email Myron Madden at mmadden@timesfreepress.com.