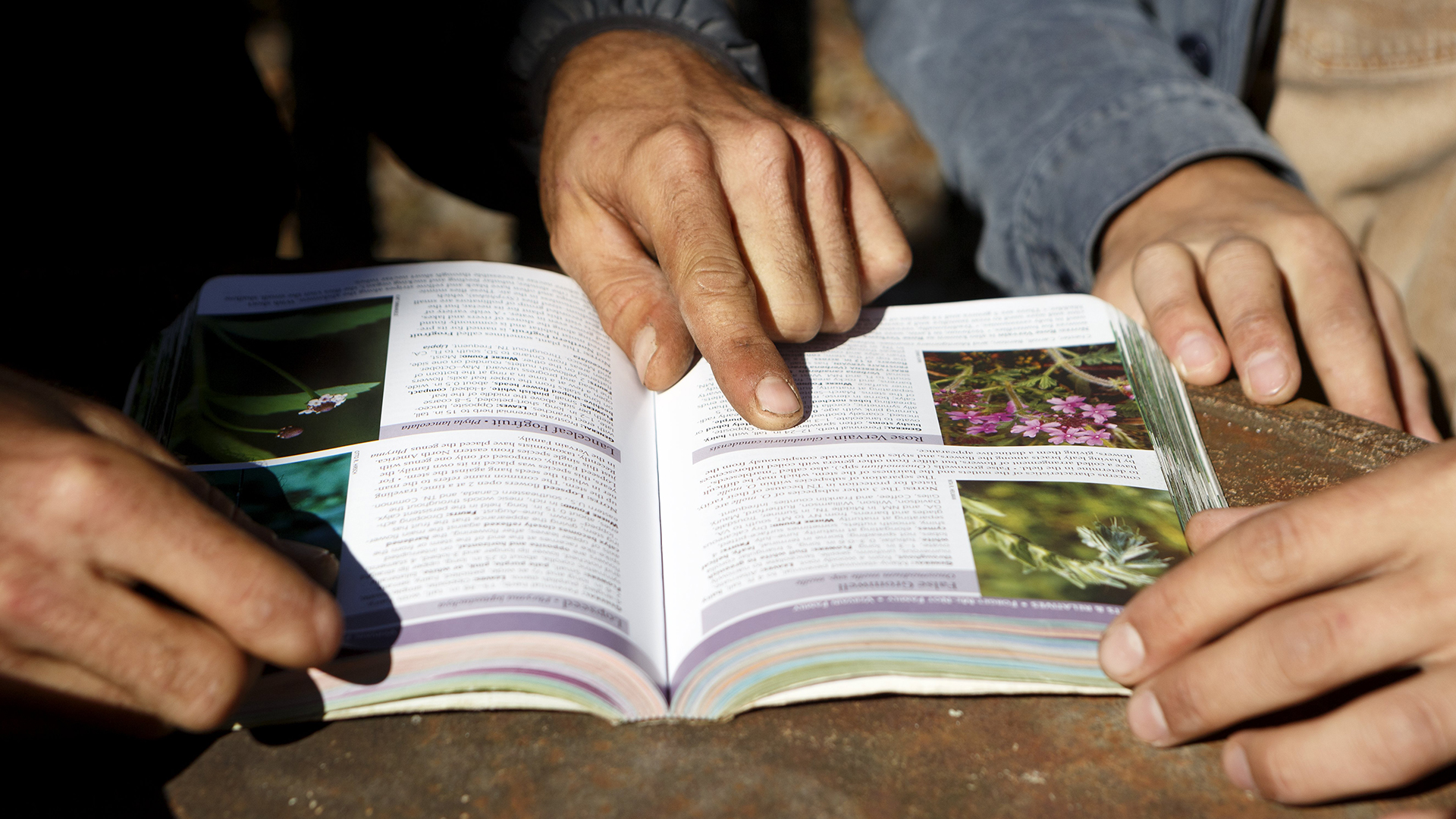

Being able to identify plants and flowers takes time, says Reflection Riding Arboretum & Nature Center nursery manager Scott Smith. For eight months he threw himself into the learning process, wandering the woods with a plant identification book. Yet there are still times when, examining the fuzz on a stem or analyzing the primary colors of a flower's petals, he must pull out his reference material.

It's not just a study of botany, but of history as well.

The scientific names of plants are known as botanical nomenclature, a classification method which can be traced back to 300-400 B.C., says Dylan Hackett, a horticulturist at Reflection Riding. These names speak to the herbal remedies for which the plants were utilized, he says. But from region to region, plants and flowers had different common names derived from these uses, so a science-based Latin name was added. The first part of a plant's scientific name is its genus and the second part is its species, often a derivation of the plant's historical common name.

The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature is based on this two-name system developed by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in the 1700s. However, most people aren't an encyclopedia filled with the Latin names of plants, Hackett says.

Roots of other plant names

Here are some of the more interesting origins of other native species, according to Dylan Hackett and Scott Smith.* White snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) was, not surprisingly, used to treat snakebites. However, the root also transmits its own toxin, tremetol, from cow’s milk to humans. Known as “milk sickness,” this was believed to have killed Abraham Lincoln’s mother.* The basal leaves of the compass plant (Silphium laciniatum) align in a north-south direction, facing the sun in the morning and afternoon.* Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) is so called because dew beads up on the leaves in the morning, lending a jeweled appearance. Hackett and Smith also say it’s a “jewel” of a plant because it can alleviate poison ivy.* Eupatorium perfoliatum is commonly called boneset because, according to the 19th century book “King’s American Dispensatory,” it relieved influenza’s “deep-seated pain in the limbs.”* Cross vine, the common name for Bignonia capreolata, is derived from the cross that can be seen in a stem cross-section.

Today's common names for plants can come from a variety of roots and still vary from region to region. The everyday names of wild plants in Tennessee, for example, come from the uses of indigenous people, he says.

The common name for Eutrochium - known in this area as Joe Pye Weed - comes from the tale of an indigenous medicine man whose Christian name was Joe Pye. He treated colonials with the mauve flowers found across North America, and the association stuck.

The Lobelia cardinalis, meanwhile, gets the latter part of its name from the vibrant scarlet robes worn by Catholic cardinals. Today, it's commonly known simply as the cardinal flower. The name of its cousin, the Lobelia siphilitica, literally means "of syphilis" because of its past use as a treatment for syphilis. In today's world of antibiotics, it's commonly called the great blue lobelia owing to its rich color.

Then there are plants with names directly related to their interactions with humans. The "dog hobble" (Leucothoe fontane) hearkens to the days of early settlers. When traveling through thick tufts of the shrubs, the difficulty would hinder the dogs to hobbling, Hackett explains.