Two years ago, the sudden death of Rachel Held Evans at age 37 left a community of spiritual seekers in shock and heartbreak. A best-selling author and provocative thinker, Evans and her work had offered a home for a diaspora of believers wrestling with evangelical Christianity, a community yearning to seek God, find safety amid doubt and include those whom the churches of their youth had rejected.

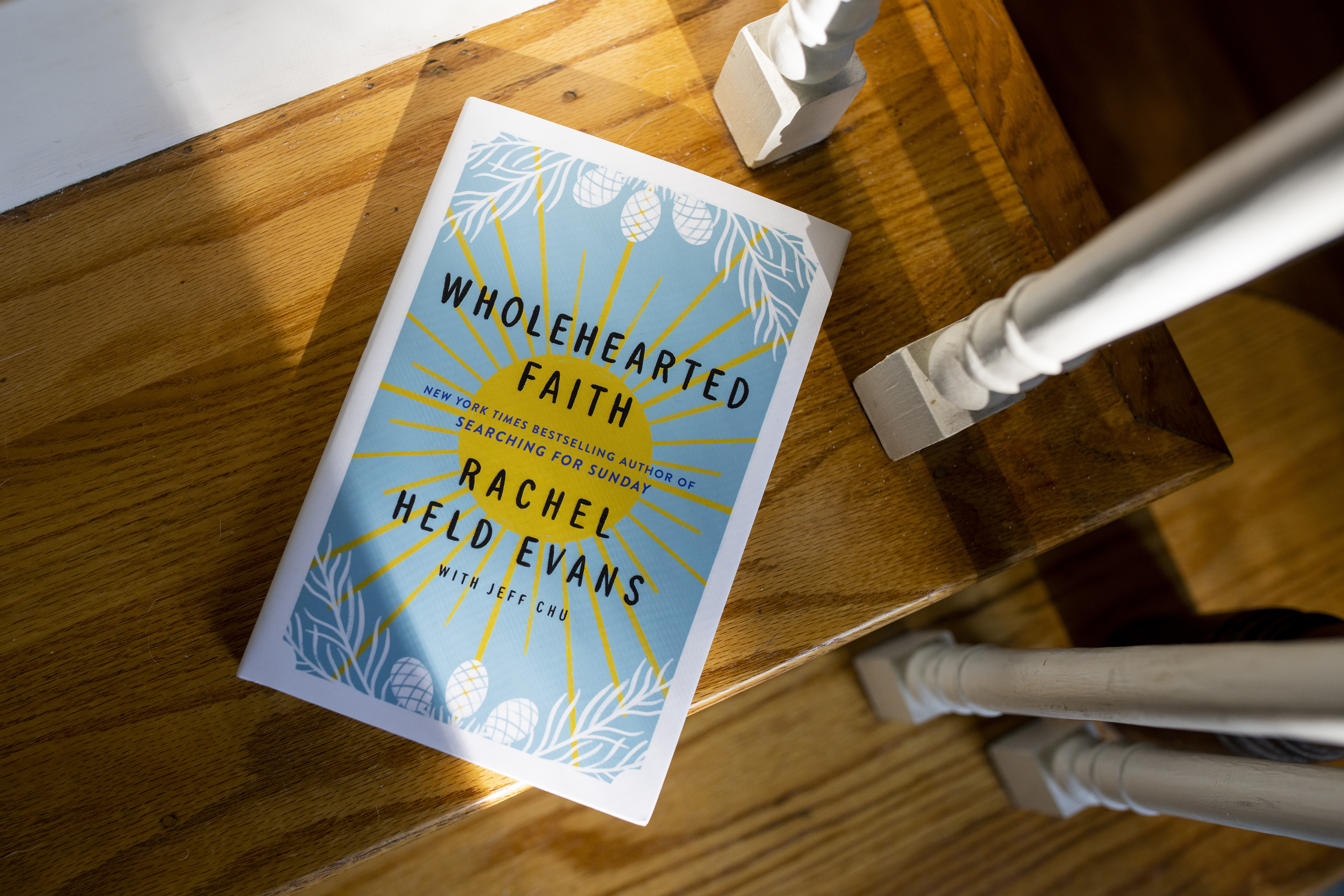

She also left the beginnings of an unfinished manuscript, what she had hoped would be her sixth book: an exploration of spiritual wholeness, to be called "Wholehearted Faith."

In the months that followed, Daniel Jonce Evans, Evans' widower, gathered the 11,000 words she had already written, along with some of her other unpublished writings, and asked her friend and fellow author Jeff Chu to knit them together to finish what she had begun.

Those words have now been published for the first time.

In a conversation with The New York Times that has been edited for length, Evans and Chu reflected on Rachel Held Evans' legacy, her new essays and how to face life's unanswerable questions about death, love and hope.

Q: What happened after Rachel's funeral? How did you begin to keep going?

Evans: The first thing you do is the next thing. So much of life immediately after the funeral was just doing the next thing. Trying to figure out what it means to be a single dad and widowed and balancing a certain responsibility that I felt towards Rachel and her audience at the same time that I'm trying to figure out who I am. It is identity shifting. My daughter, Harper, wasn't even a year old, and her first birthday happened between the time Rachel died and the funeral. So I had a newly 1-year-old and a 3-year-old, and so much of life was just the everyday things that that requires.

As I thought I was emerging from this - saw some light at the end of the tunnel - is right when COVID hit. So then it was isolation. You all go to your own family units, and my family unit was one I hadn't even figured out. That was probably one of the lowest points for me. There was one point when my daughter threw up on the carpet, and I didn't have a good way to clean it up, and I just covered it with a towel, and I left it that way.

Q: What does life look like now?

Evans: I feel like we're getting in a regular pattern. There was a house that Rachel and I had just started building when she got sick. I finished building that, and we moved into that last December. I'm in a relationship now with an amazing woman, and she's a big part of our life. The kids are starting to go to school, and we're starting to learn how to navigate a new, unexpected life.

Q: How did this book come about?

Evans: One of Rachel's worst nightmares was to die with a book unfinished. She had expressed it a couple of other times with previous books. Jeff was one of the people who was there in the hospital the night that Rachel died. I knew that this book she had been working on was something that was important to her and I think could be important to her readers. It was such an easy choice to be like, "Hey, is this something you would be willing to take on?" He was like, "I'll do anything that'll help you and the kids." I had just made a lot of difficult choices. This one was so easy.

Q: Jeff, what was that like for you, taking this on?

Chu: The decision to say yes to Dan and the kids was not difficult. Actually following through and finishing the book was really difficult. But this is the thing about friendship - I don't think that friendship is always just easy. Sometimes friendship is going to ask us to make sacrifices and take hard roads and do things that aren't necessarily delightful or fun, because that's what our friends need.

Q: For Rachel, what would it mean to strive for wholehearted faith, in this moment?

Evans: If you want to see somebody who's wholehearted, it was Rachel. Part of wholeheartedness is that ability to be vulnerable. She was able to approach her doubts and the things that used to be considered scary or bad in her faith tradition and say, actually, it's a strength to be able to acknowledge these.

Q: There's a line when she says, "Christianity is the story I will wrestle with forever." Tell me about that.

Chu: Rachel often would say, "On the days when I believe ... " That's a line that shows up over and over in her talks and in her writing, and I think it was a candid acknowledgment of the reality of faith for so many of us. Christianity is, let's be honest, a super-weird story. And it's also an invitation to ask big questions. How do you not ask big questions about the suffering in this world? And how do you not ask big questions about this super-weird story? One of the gifts that Rachel gave me, and I think one that she left for the world, was her gentle encouragement to keep wrestling, to keep asking questions, to keep seeking because all of this is complicated. But ultimately, I think she believes the love that was underneath all of it was worth chasing.

Q: There's a theme in the book of how interconnected we all are, even beyond time. What does it mean to carry on the life and love of someone after they have died?

Evans: I used to think that "'til death do us part" meant that everything ended when one person died. And what I'm learning is that there are some things that exist until both people are in the grave. Sounds super morbid and depressing, I'm sure. But there are some things that currently are still painful, but I hope in the future I can look back on with a smile, like all the shared jokes that only two of us knew, and now just one of us does. The life that we imagined together, and now I'm the only one that can imagine it, as we did.

Chu: The way that Rachel approached the big things sometimes was the beautiful agglomeration of little gestures. Sometimes I think people perceive fighting for justice, for instance, as this thing you do at the Capitol or this thing you do at a march. And the reality is, yes, it can be that. But how I experienced justice through Rachel's friendship was coming alongside [my husband and me], a gay, interracial couple, and just being their friends. It's making room in your life in an intimate and caring way. It's treating people not as just a couple aspects of who they are, but encountering them for their full humanity. And she teased me relentlessly for my biases and weaknesses. So she made room for those, too.

Q: Can we talk about the end? She writes, "With God, death is never the end of the story." How do you understand that?

Chu: I don't understand it. Do any of us really understand it? I think anyone who claims certainty on what happens after we die is to some degree pretending, because we can't know, but we can have hope. We can hope in resurrection, we can hope in some form of reunion with those we love. We can hope that memories live on. We can hope in some semblance of an afterlife. But I'm not going to pretend to tell you that my imagined vision of what that might be is any more real or accurate than yours or that of someone halfway around the world from a completely different belief system. That would just be absurd.

A portrait of the late author Rachel Held Evans at the home of her husband, Daniel Evans, in Sale Creek. She gave voice to a generation of wandering evangelicals wrestling with their faith. Two years after her sudden death at age 37, Evans has one more message. / Photo by Peyton Fulford/The New York Times

A portrait of the late author Rachel Held Evans at the home of her husband, Daniel Evans, in Sale Creek. She gave voice to a generation of wandering evangelicals wrestling with their faith. Two years after her sudden death at age 37, Evans has one more message. / Photo by Peyton Fulford/The New York TimesQ: Dan?

Evans: I just don't know.

Q: What do you do when you just don't know? There are a lot of people who just don't know.

Evans: I think sometimes in religion, we're presented with things that we don't know, and we don't have to make a choice. We can keep searching and learning more without being forced into a false sense of urgency. And so sometimes when I don't know, I learn how to sit with that discomfort. I realize I don't know, but also, I don't have to know.

Q: Is this really it? Is this the last time people will hear from Rachel? Are these really her last words?

Evans: This is the last book for adults. She was working on four children's books total; it's hard to know for sure what will happen. It's taken me a while to really just believe the truth that Rachel is not going to write any more books. I mean, I know it's true. But to feel it to my innermost self, to actually just feel it, it's taken me a while to come to grips with that. This is not the last time that her influence will be apparent. And I don't know exactly what that means, but I'm confident that it's not the last time we've heard from her.

Chu: I'm also mindful of how annoyed she would be with us for elevating her to some heroine status, for making her out to be some saint. In my mind, I hear her yelling, "Jeff Chu, stop it!"

Evans: And all of us have the Rachel voice with us forever, don't we?