Read more

Chattanooga area vaccination rates rise, but questions remain

REQUIRED VACCINES

The following are the immunizations required before entering kindergarten in Tennessee:Measles Mumps Rubella Poliomyelitis Hepatitis B Hepatitis A Varicella Tdap Booster DTP, DTaP, DT, Td Source: Tennessee Department of Health REQUIRED VACCINES The following are the immunizations required before entering kindergarten in Tennessee:Measles Mumps Rubella Poliomyelitis Hepatitis B Hepatitis A Varicella Tdap Booster DTP, DTaP, DT, Td Source: Tennessee Department of Health

Dr. Bill Schaffner still remembers the hot summers of his childhood, when he was not allowed to cool off in the public swimming pools.

His parents were too worried about him catching polio.

He remembers the lines that snaked around the block when the polio vaccine came out in the 1950s. And he remembers when the federal government declared in 2000 that measles had been eliminated in the United States.

"We thought we had licked these diseases," said Schaffner, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. "We were thinking, 'What can we get rid of next?'"

But now Schaffner and other leading infectious disease doctors in the U.S. find themselves gearing up again for a public health battle they had long assumed was over: Childhood vaccinations.

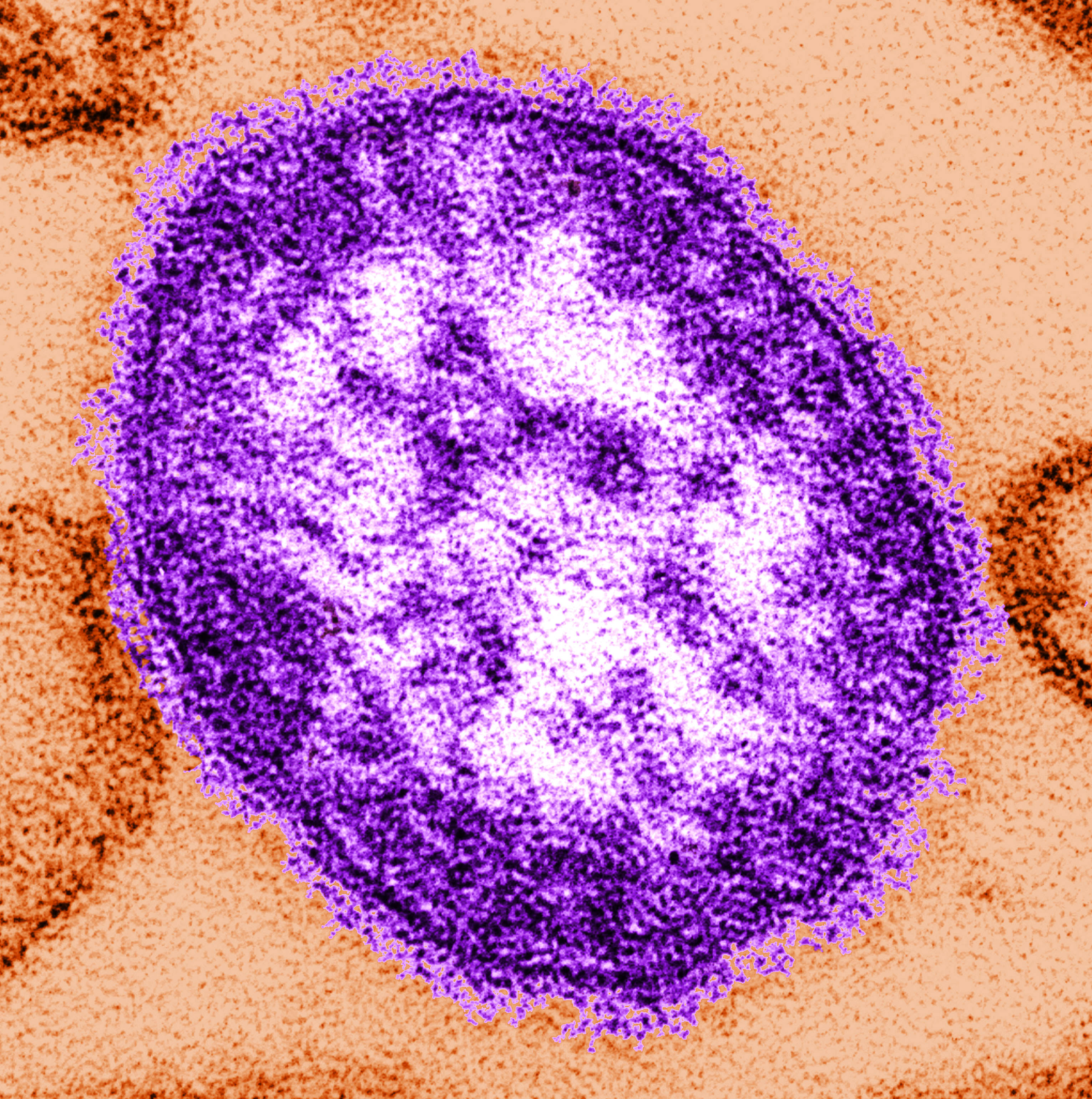

Conversations that typically take place between parents and doctors inside examination rooms have erupted again on the national stage because of the largest spike in measles cases in the last two decades. The 150-person, 17-state outbreak traced to Disneyland is "far and away the most dramatic" byproduct of the anti-vaccine movement, Schaffner says.

Doctors once dismissed the anti-vaccine movement, spurred by widely debunked claims that linked vaccines to autism, as a fad.

But the growing movement has prompted lawmakers across the U.S. to rethink laws that have allowed parents to opt out of vaccine requirements for philosophical or religious beliefs. This year, at least 10 states are considering legislation to limit such exemptions, Reuters has reported.

The laws have won bipartisan support, and include everything from eliminating exemptions to requiring schools to post more detailed vaccination information.

And such policy is crucial, some doctors say, in the face of a debate that is only picking up steam.

"Based on what's happened over the last decade, vaccine skepticism is not going away," Schaffner said. "The need for policy and education is absolutely there. If anything, it will grow."

No bills concerning childhood vaccinations are pending this year in either Tennessee or Georgia, though both are considering laws relating to meningitis vaccine recommendations for college students.

Both states have somewhat narrow childhood vaccination laws: They allow parents to opt out for religious and medical reasons -- known as a philosophical exemption -- but not for personal beliefs.

The result is comparatively high vaccination rates. About 95 percent of Tennessee kindergarten students in public and private schools received the required immunizations last year. Just over 1 percent claimed religious or medical exemptions. Less clear is the status of children who did not fulfill the requirement because they are missing proof of vaccination at the time of the surveys.

Despite this high level of protection, Tennessee still saw four cases of measles in 2014 -- its first cases in three years. Between 1995 and 2013, only nine cases total were reported in the state.

"While we can be proud of our relatively high rates of vaccination in Tennessee, even higher rates would offer greater protection from outbreaks and for vulnerable populations who cannot be effectively vaccinated," Tennessee Health Commissioner Dr. John Dreyzehner said in a statement.

Some doctors, like Schaffner, believe those numbers could be upped by being more stringent on religious exemptions or doing away with the exemption altogether.

"We don't have religious exemptions for parents who want to leave the hospital with their baby without a car seat," he said. "Why should we have one for vaccinations that protect children from life-threatening diseases?"

The choice to vaccinate goes beyond an individual child, doctors say. It's about creating a "cocoon of protection" for children who are especially vulnerable to disease and who cannot be vaccinated because of cancer treatment or other health problems.

"This is a bigger issue than 'what I want or don't want for my child,'" said Connie Bueckner, communicable disease program manager for the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Health Department.

Doing away with religious exemptions is not unprecedented. In Mississippi, for example, the state's Supreme Court upheld a vaccine requirement for school enrollment with no religious exemption, stating that such opt-outs put children at risk.

But such laws have also spurred fierce opposition from advocates who insist that parents, not the government, should decide what's right for their children.

"We consider this an assault on human rights," said Barbara Loe Fisher, director of the National Vaccine Information Center, a Virginia-based nonprofit that monitors vaccine legislation. "You should have the right to make a fully informed, voluntary medical decision without being punished for it."

Fisher has called the last eight weeks "unprecedented" in terms of vaccine-related legislation, and said that rhetoric about "the greater good" is actually adversarial and discriminatory when it comes to singling out unvaccinated children, whose parents may have legitimate reasons for refusing to vaccinate them.

"You cannot say that one child's life is more important than another's," she said.

Health officials say the policy is not the only method through which they can push parents to vaccinate.

"A growing number of pediatric groups simply will not see patients unless they are vaccinated," said Bev Fulbright, epidemiology manager at the county health department. "That can be a huge influence."

And Schaffner wants vaccine education to become more standardized in schools, so parenthood is not the first time people are exposed to the questions surrounding it.

"Kids don't learn about vaccines and the illnesses they prevent because, well, we've eliminated those diseases," he said. "We need to keep it that way."

Contact staff writer Kate Belz at kbelz@times free press.com or 423-757-6673.