As part of their yearly training, East Ridge police officers used to stand before a now-retired instructor who would read use-of-force policies out loud and make the officers repeat after him.

One of those policies instructed the roughly 45-person department that "arterial and or neck restraints (chokeholds) are considered lethal force and will not be used" when dealing with people trying to run from serious charges. As a result, East Ridge officers were not trained to use them and are not to this day.

Though each academy and department varies on training and policy, East Ridge's position wasn't uncommon: Over the years, law enforcement agencies in Atlanta, New York, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., have banned chokeholds because they can cut off a person's windpipe and cause suffocation, brain and spinal damage, other serious bodily injury or death.

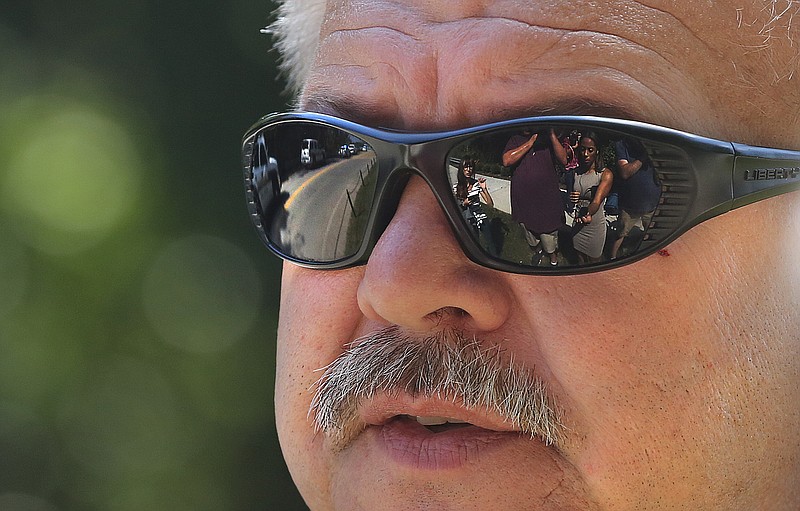

This screenshot of the footage taken by a police bodycam shows the moment when an East Ridge police officer wrapped his arm around Christopher Penn's neck in an attempt to subdue him during an Oct. 21, 2018, arrest. Critics have called the move excessive and a potentially deadly use of force. Police maintain the officer used a "lateral vascular neck restraint," which does not restrict a person's ability to breathe and is considered safer than a traditional chokehold.

This screenshot of the footage taken by a police bodycam shows the moment when an East Ridge police officer wrapped his arm around Christopher Penn's neck in an attempt to subdue him during an Oct. 21, 2018, arrest. Critics have called the move excessive and a potentially deadly use of force. Police maintain the officer used a "lateral vascular neck restraint," which does not restrict a person's ability to breathe and is considered safer than a traditional chokehold.For whatever reason, now-suspended East Ridge Police Chief J.R. Reed amended that policy in May 2015 with a new one that doesn't mention neck restraints or chokeholds. The Times Free Press obtained a copy of that 2015 policy through a public records request and had medical, legal and law enforcement experts review it. Both the new and old policy are relevant in light of a recent arrest that critics say involved a chokehold on a 27-year-old handcuffed man who was resisting while handcuffed.

"As a liability trainer, if you leave things out, then you're asking for trouble, especially with something as critical as a force option," said Mark Wynn, a former Nashville police officer who consults for departments worldwide.

Reed could not be reached for comment and is reportedly being investigated for three or four policy violations. But Assistant police Chief Stan Allen said Wednesday that officers used "reasonable force" and didn't violate any department policies when they shocked Christopher Penn in the testicles and put him in a neck restraint on Oct. 21 around 4 a.m. They were not disciplined and continue to work, Allen said.

Allen, who has been at the department for about three and a half years, said he wasn't aware of the old policy. He called the force a "lateral vascular neck restraint," though critics who reviewed body camera footage of the incident say it was a chokehold, which is different.

"There appears to be a disconnect," said Chattanooga defense attorney Robin Flores.

Officers who created a report the same day as Penn's arrest also referred to the hold as a "lateral vascular restraint." But details in that report don't fully match up with police body camera footage, which shows an officer saying he "choked" Penn out.

A lateral restraint involves pinching the arteries below a person's neck, which stops blood flow and causes a person to briefly pass out; a chokehold is when you bar someone's windpipe, which, unlike a lateral restraint, can affect their ability to breathe.

According to the body camera footage and report, Penn called 911 on himself around 4 a.m. on Oct. 21, said he'd taken pills and claimed his friend had let people into a home on Welworth Avenue who wanted to kill him. That wasn't the case.

Though Penn allowed officers to handcuff him for misuse of 911, a misdemeanor, he tried to run three or four times, bucking, thrashing and pulling five officers across the street. After one officer claimed he kicked her, another reached over and held his stun gun to Penn's testicles for five seconds. A few seconds later, an officer put him in the hold and lifted a gasping Penn off the ground, causing him to lose consciousness.

"It was necessary force," Allen said of the arrest. "Christopher Penn continued to fight no matter what the officer did until they used a lateral neck restraint. I would appreciate if you didn't use that language [about chokeholds]. A chokehold implies cutting off the air supply."

Bill Smock is a doctor for the roughly 1,200-person police department in Louisville, Ky., who advises his chief on use-of-force policies and teaches strangulation courses to departments. After reviewing body camera footage of the arrest, Smock said Penn's breathing was "compromised."

"Listening to the audio of his respirations, he clearly has respiratory compromise as well as bloodflow compromise," Smock said. "That means he was having trouble breathing. There was enough swelling to his airway that it indicates a compromise to his ability to breathe."

Smock said his officers are forbidden from using chokeholds unless it's a life-or-death situation. In May, a former school resource officer in Kentucky was tried on assault and misconduct charges for lifting a 13-year-old off the ground in a chokehold. The now-fired officer testified the teenager had knocked him down in a crowded hallway. A jury found him not guilty.

In recent years, Tennessee has amended its criminal code to include harsher provisions against strangulation. The Senate voted in April 2015 to define an incident as aggravated assault when a defendant "knowingly or intentionally committed assault involv[ing] strangulation or attempted strangulation," a Class C felony.

Melydia Clewell, spokeswoman for Hamilton County District Attorney General Neal Pinkston, said his office is aware of Penn's incident. She did not comment on whether Pinkston would ask the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation or the Hamilton County Sheriff's Office to further investigate.

Though it's not uncommon for prosecutors to do that with allegations of local officer misconduct, spokeswoman Susan Niland said the TBI had not yet received any request to investigate as of Tuesday.

Under East Ridge's current policy, officers have to evaluate a couple of factors to determine if their force was "objectively reasonable." How much of a threat or foreseeable threat was the person to officers? Was the person trying to escape? How severe was the crime involved? Was the situation rapidly escalating?

Policy says officers are allowed to use stun guns if a person is actively resisting. But Axon, a company that makes and sells stun guns, said it trains officers to "avoid sensitive areas" such as the testicles.

After the incident, officers drove Penn to Parkridge East Medical Center, left and later took out arrest warrants for misuse of 911 and assault against two officers. Records show Penn turned himself in on Oct. 20 and since has made bail.

His first hearing in East Ridge Municipal Court is Jan. 15. He had no listed attorney as of Wednesday.

Contact staff writer Zack Peterson at zpeterson@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6347. Follow him on Twitter @zackpeterson918.