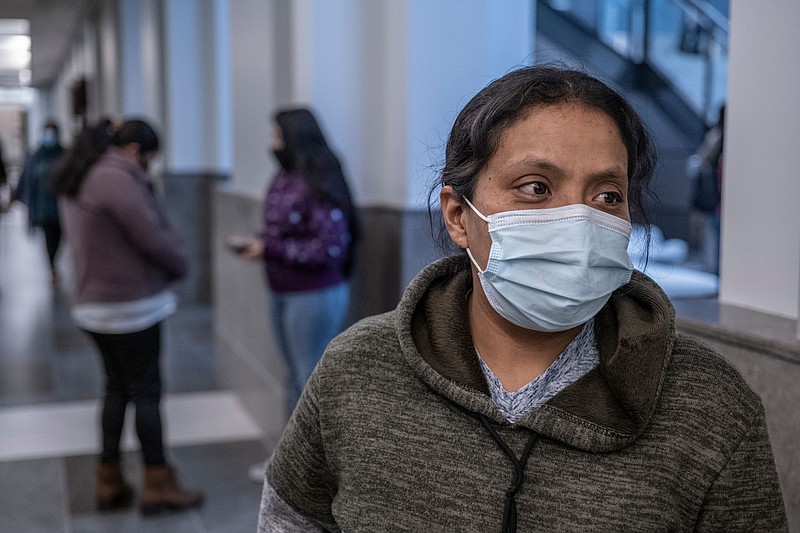

For Maria Hernandez, 36, this has been a stressful year. Her husband was deported in February due to domestic abuse. And although it was for the best, she hasn't recovered financially. After months of trying to find work in a pandemic, Hernandez and her six children were about to be evicted, despite a national moratorium on evictions.

"Everything happened at the same time," Hernandez said.

Hernandez cleans houses for a living, but that work has dried up since early April. What little money she received through miscellaneous jobs went to her children, ages 5 to 15. Recently she started working full-time again, since clients were no longer as fearful of having their homes cleaned, but by November she owed $5,000 in back rent. It was impossible to catch up. Her landlord's lawyer asked for $7,000 to drop the suit.

"The situation has gotten complicated for me," she said.

Hernandez also said she didn't blame her landlord for taking her to court.

Although the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a moratorium on evictions, cases have started filling courts, either because of issues unrelated to the pandemic or because people were unaware of the moratorium and that they needed to fill out a form to avoid eviction.

As many Americans face eviction, the immigrant community faces unique challenges. Immigrants are often reluctant to report problems with landlords due to language barriers, legal status or because they're in the process of becoming legal residents and fear delays. In Chattanooga, the Latino population currently accounts for 14% of all COVID-19 cases, while they are about 6% of the general population.

Unemployment rates have risen sharply, especially among Hispanic women, as many low-wage jobs were unavailable. About 6 in 10 Latinos reported living in households that have experienced job loss or pay cuts due to the outbreak, according to the Pew Research Center. Many face eviction due to limited resources.

Federal and state coronavirus relief funds were allocated to nonprofit groups to distribute for rent assistance, but resources are limited for undocumented families since most nonprofits require documentation, according to Luis Sura, whose organization, Better Options TN, is providing relief to undocumented families.

Since funds became available in September, Conexión Américas in Nashville raced to distribute rent relief to struggling immigrants. By November, staff had distributed $400,000, or an average of $4,000 per household. But there are still too few resources for immigrants, and immigrants are often unaware of the aid available to them, according to Martha Silva, spokesperson for Conexión Américas. The organization is confined by federal guidelines, which are often "black and white," said Silva, such as aiding single mothers unable to afford child care.

"There are so many cases that to me make sense and I would love to approve, but, of course, we have to follow the guidelines of the CARES Act," Silva said.

Conexión Américas has battled to inform immigrants of their rights in avoiding eviction during a pandemic, since many fear legal retaliation if they speak up. Unauthorized immigrants are an especially vulnerable population, and landlords may choose to take advantage of their situation. Silva has received numerous reports of landlords charging exorbitant late fees, raising rent without notification and blackmailing immigrants.

"They use [legal status] against them. They say 'You don't have any rights. If you don't pay rent, we can just kick you out and if you don't agree, we will call the police and you'll get in trouble,'" she said.

Renters, regardless of immigration status, have a certain amount of rights. A landlord cannot evict tenants without notification and without serving a 30-day notice. Landlords cannot change the locks or increase rent until the lease is over.

Few legal resources are available to immigrant families, and in these situations, Conexión Américas cannot provide legal representation to undocumented families. For documented families, they are referred to the Legal Aid Society of Middle Tennessee and the Cumberlands, a non-profit law firm that provides free legal services for low-income families.

Kerry Dietz, an attorney at Legal Aid, tries to help undocumented families in any way she can, such as compiling a referral list.

"I can't tell you how many hours I've spent this year of my work just trying to figure out what's going on, what help is out there. What does this moratorium mean? What does that moratorium mean? Who is protected? Who isn't? Just trying to keep track of that has been a huge part of my job this year," Dietz said.

A lack of documentation means there's little data on how widespread the problem is. Immigrants are a lot more likely to move out without conflict, according to Dietz, and may be moving into crowded housing situations, which is dangerous during a pandemic.

Hernandez was one of the lucky ones. She attended court with no legal representation and was about to get evicted, but the Nashville Conflict Resolution Center was able to intervene and pay Hernandez's $7,000 debt, giving her and her children a fresh start.

More from Tennessee Lookout.