For many Tennesseans, the COVID-19 vaccine is a one-size-fits-all solution to returning to pre-pandemic normalcy, but for Black and immigrant Tennesseans, the trials and pending vaccinations are exposing long-standing health inequities in minority communities.

The COVID-19 vaccine has arrived in Tennessee and is being distributed to health care workers first. It's expected to become available publicly in January, which means addressing mistrust in minority communities.

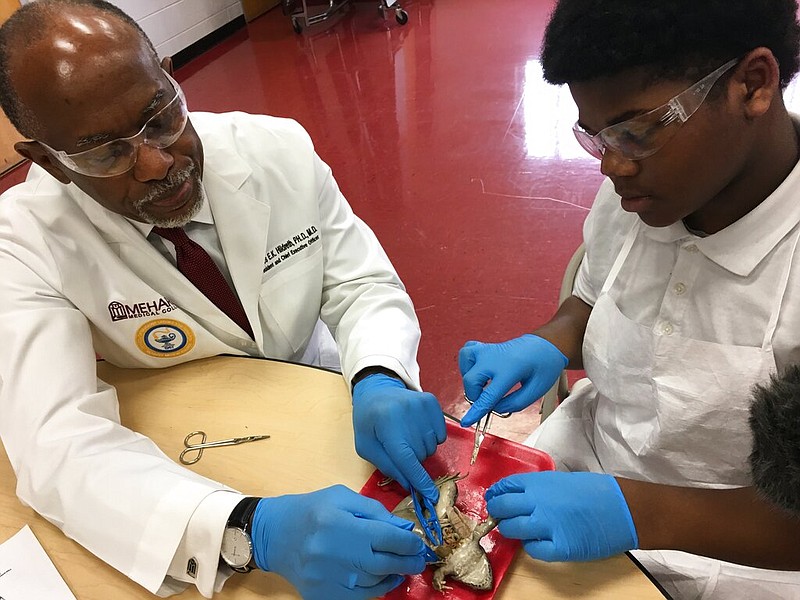

At Meharry Medical College in Nashville, officials have been working to be seen as a source of trusted information for minority communities since the beginning of the pandemic. Meharry officials have been collaborating with community leaders to help prepare communities for the vaccine, especially the Latino and Black communities.

"We see ourselves as being embedded in the community. This is not new to us..it's something we've always done since our inception. I say that to say that there's a level of trust, and a lot of times when there's a lot of uncertainty around health care, people are going to look to those they trust for guidance, and Meharry certainly sees itself in that role," said Dr. Charea Farmer-Dixon, dean at Meharry's school of dentistry.

In preparing the community, Meharry officials hope that when someone hears something, they come to their website to get trusted information. As the vaccine becomes available, Meharry plans to "make (information about it) as widespread as we can," said Dr. Paul Juarez, professor and vice chair of Research of Family and Community Medicine at Meharry.

As one of the nation's oldest and largest historically black academic health science centers, Meharry officials understand they have a better chance of reaching minority communities and addressing deep-rooted mistrust.

"There's a bigger issue when we talk about clinical trials, and that bigger issue is addressing mistrust. We have to find ways to address deeply rooted mistrust in the health care system, which is going to take a little more time and a little more effort based on past traumas," said Reginald French, president of the Sickle Cell Foundation of Tennessee.

Each community has its own concerns about the vaccine, especially the Latino and Black communities, which have been a primary target for Meharry officials.

Latinos and Black Americans have a different but similar hesitancy with health care systems. Throughout the pandemic, the Latino community has struggled with receiving much-needed government assistance while having private information in the hands of government officials.

A controversial decision to share COVID-19 patient names and addresses with law enforcement by the Tennessee Department of Health was halted in June after a public outcry over the privacy implications. Immigrant rights advocates feared undocumented families would not seek medical care for fear of immigration authorities and that death rates in the community would rise as a consequence.

Guidelines have not made clear whether participants will need identification to be vaccinated. The vaccine will be administered in two doses, which means health officials will need to track participants. For many Latinos, fear stems from documentation status and others have trepidation about officials having private information on those who receive the vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccine regulations may depend on federal, state and local governments.

"There's going to be a lot of hesitancy in the Latino community about giving up personal information," Juarez said.

The Black community has similar concerns about private information being shared with police and their own troubled history with medical trials has given the community well-founded fears of the health care system.

Two major historical events have contributed: the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the case of Henrietta Lacks.

Between 1932 and 1972, 600 Black men unknowingly participated in an experiment to document the effects of syphilis, and several hundred were purposely infected. And in 1951, Henrietta Lacks, 31, died of cervical cancer, but not before doctors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore took samples of her cells without consent.

To this day, Lacks's cells, called HeLa cells, have been used to make key discoveries in modern medicine, including breakthroughs in cancer, immunology and infectious disease. The Lacks family never received any compensation and for decades, medical officials failed to ask for the family's consent in revealing Lacks's name, medical records and genome publicly, according to Nature Research.

"Both of those [cases] affected the African-American community immensely," French said. "We can have a vaccine but obviously we have to deal with some reality, and the reality is the overall mistrust, and the facts are there that people of color have well-founded mistrust in the health care system," he added.

Meharry officials recognize that there are underlying issues related to the pandemic that has especially affected minority communities.

Members of minority communities have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and have been more likely to die from COVID due to underlying conditions, such as access to health care and underlying health issues. This has prompted Meharry officials to put together a community resource guide for people affected by COVID on a regional basis throughout the state.

The directory has detailed information on bill and food assistance. About 200 different organizations, primary care providers, behavioral specialists and dentists have collaborated to reach vulnerable communities.

"It's not just their health that's affected, it's all aspects of their lives," Juarez said.

Misinformation has also been an overall problem in minority communities.

"What we've seen leading up to this age, in terms of the vaccine, is that the amount of misinformation just leads a lot of people somewhat paralyzed. They don't know what to do or who to believe and we are trying to provide them with access to look up the correct information," Juarez said.

Meharry officials and community leaders encourage everyone to get the vaccine. The Moderna vaccine has had a 95% success rate and is in its Phase 3 trial, meaning that thousands of people have participated in several vaccine trials across the world.

According to Pfizer, data demonstrated that the vaccine was tolerated across all populations with over 43,000 participants enrolled. No serious safety concerns were observed; the only Grade 3 adverse event greater than 2% in frequency was fatigue at 3.8% and headache at 2.0%.

Approximately 42% of global participants and 30% of U.S. participants have racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds, and 41% of global and 45% of U.S were between the ages of 56 to 85, according to Pfizer.

Tennesseans will be receiving the Moderna vaccine soon, which was "100% effective in Black, Latino and Asian Americans, as well as in people with mixed racial backgrounds," according to the Los Angeles Times.

"There's a lot that we don't know, but there's a lot that we do know, and we know it's effective in protecting people from getting COVID, from the most serious effects of COVID," Juarez said, adding that people with underlying health conditions should definitely receive the vaccine.

As the public begins to be inoculated against COVID-19, Meharry officials will still continue to study the long-term effects of the vaccine and earn the trust of minority communities in the hopes that they participate.

"It's going to take a lot of community engagement and a lot of partnering with community leaders to make communities of color feel more comfortable with it," French said.

Read more from Tennessee Lookout.