The remains of a Chattanooga man killed in 1943 on a tiny island in the Pacific during World War II and buried as "unidentifiable" in Hawaii years later have been found through DNA analysis.

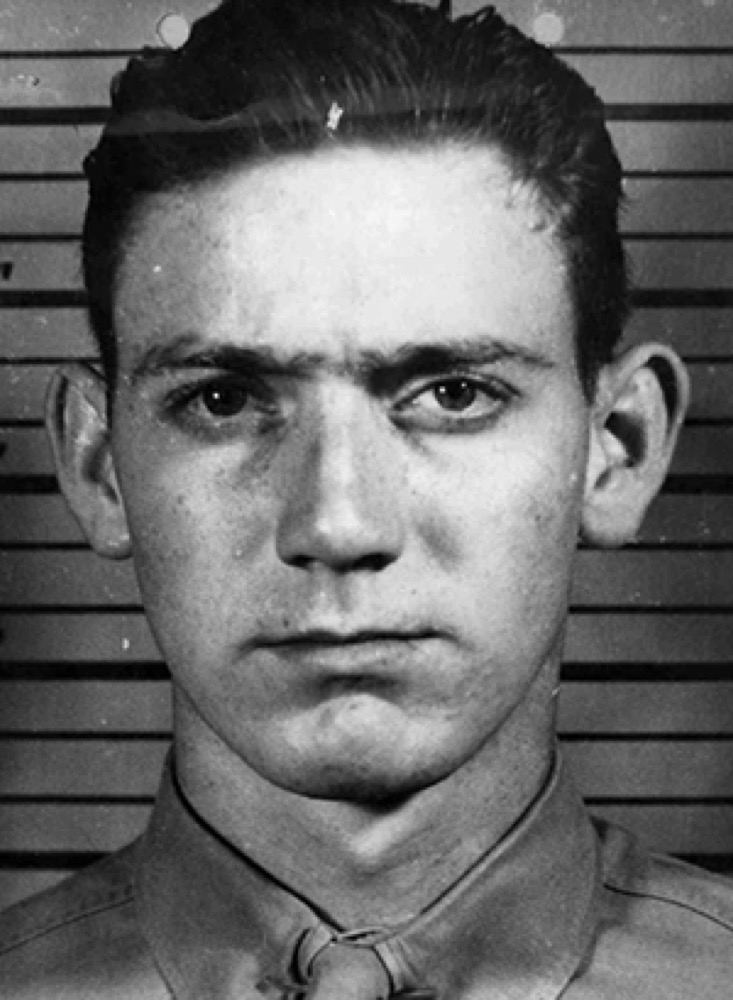

U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Thomas H. Cooper, 22, was killed on Nov. 20, 1943, the first day of action as military forces landed on the island of Betio, where strong Japanese resistance inflicted heavy casualties.

Born Nov. 2, 1921, in Omaha, Nebraska, Cooper's remains were accounted for on Aug. 9, 2019, by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency after being identified from among remains of 94 Tarawa Unknowns disinterred from the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu, according to a statement the agency released Thursday.

Rachel Lukens, a 43-year-old San Diego, California, resident who was born in Chattanooga, is Cooper's granddaughter. But she knew little of her grandfather until recently, she said Friday.

"The story has always been, 'Oh, my dad died in the war before I was born,'" Lukens said of conversations with her mother, the corporal's daughter. "I have a few pictures of my grandmother but nothing of him."

Family members say he went by his middle name, Harley.

Lukens said she and her brother, Jason Frogel, were always curious about their predecessors, did DNA testing and found Coopers in their family tree. Her mother was just as in the dark, she said.

Photo Gallery

Stem Soiree-An Event Benefiting eSTEM Public Charter Schools

eStem Public Charter Schools' hosted their first annual "Stem Soiree" event. Guests enjoyed cuisine from locally owned and operated restaurants, such as 1620, Fatsam's, and Cafe 42. Guests danced to the tunes of the locally renowned band, The Salty Dogs, and took a stroll through the silent auction. KTHV television personality, Craig O'Neill, was the Master of Ceremonies for the evening.

Cooper, who was born in 1921 in Omaha, Nebraska, enlisted in Nashville on Sept. 18, 1940, according to the East Tennessee Veterans Memorial Association. He died in "an undisclosed theater of operations," according to his death notice in the Dec. 25, 1943, edition of the Chattanooga News-Free Press.

The confirmation of his death, published on Page A1 in the Jan. 11, 1944, edition, listed the family's home in the 2600 block of East 46th Street in Chattanooga.

He was the son of Thomas G. and Alline Patterson Cooper and the brother of Katherine Brogden, Betty Sue Huckabee, Mickey and Jerry Cooper, all of Chattanooga, and Bobby Cooper, who at the time was serving in the U.S. Navy, the notice states. He also was survived by half-brother, Larry Cooper.

Harley Cooper and his wife, Rachel Campbell Cooper, who was from Wellington, New Zealand, met at a dance at the Jewish Community Center there while he was on a stopover, according to his daughter, Virginia Frogel.

Frogel didn't really know anything about her father until she was school age.

"I don't know how old I was - probably 5 or 6 - and I found a Purple Heart in my mother's jewelry box and I was wearing it. And I wore it to school - I thought it was really neat but I didn't really know the impact behind it and that's when she told me," Frogel recalled Friday.

"I knew I didn't have a father but I never knew what happened till then," she said.

It would be decades before she would learn more.

"I never really thought about it," Frogel said. "I lived my life without my father and I didn't really associate what was happening.

Frogel said the family didn't know about the remains being identified until December 2019.

"We had no idea this recovery was going on," she said. "They spoke to several of his family members in Chattanooga and it wasn't until then that they found out that he had a direct descendent, me. The POW/MIA liaison officer contacted me in December."

The effort that "got the ball rolling" sprang from the work of Harley Cooper's brother, Jerry, and their cousin, Larry Ward, according to Marjorie Cooper, Harley Cooper's sister-in-law and the widow of Jerry Cooper, who provided the DNA.

Ward was the one who notified the right people, she said.

"They started talking to us and telling us that we were the ones to handle [arrangements] and we said, 'Well, he has a daughter,'" Cooper said. That led accounting agency officials to Harley Cooper's daughter and granddaughter, she said.

An online site created by New Yorker Geoffrey Roecker that is dedicated to U.S. Marines missing in action and their stories, missingmarines.com, details portions of Cooper's life.

According to Roecker's research, Cooper, his older sister Katherine, and his parents moved frequently in Cooper's youth, first living in Georgia and then in Tennessee. The family lived in Detroit long enough to be listed there on the 1930 census, according to Roecker, who used military records, National Archives and talked to family members.

Cooper dropped out of school, almost certainly to help support his family, and went to work at the Richmond Hosiery Mill in Chattanooga, according to Roecker. Cooper was sent to Parris Island for training, then to the Naval Air Station in Jacksonville, Florida. But instead of flight school, "he worked as a specialist carpenter and painter, feet planted squarely on the ground," Roecker wrote in his profile of Cooper.

"In late 1941, around the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Cooper was transferred to Dunedin, Florida, for training as an amphibian tractor crewman, Roecker wrote. He first learned the craft of a gunner, but showed some mechanical aptitude and in January 1942 was promoted to corporal and, possibly, reassigned as a driver. Corporal Cooper's Company A would ship overseas in July of 1942 and be among the first "Alligator" Marines to see combat during the Guadalcanal landings the following month."

Roecker also uncovered some details about Cooper's romance that followed the end of that fighting.

"When the campaign ended, they traveled to New Zealand for training, rest, and recreation. Many Marines fell for the local 'Kiwi' girls, and Cooper was no exception," Roecker wrote. "He married his girlfriend in 1943."

***

Cooper's fate would soon change.

In November 1943, Cooper was a member of Company A, 2nd Amphibious Tractor Battalion, 2nd Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force, which landed against stiff Japanese resistance on the small island of Betio in the Tarawa Atoll of the Gilbert Islands in an attempt to secure the island, accounting agency officials said in Thursday's statement. Over several days of intense fighting at Tarawa, about 1,000 marines and sailors were killed and more than 2,000 were wounded, while the Japanese were virtually annihilated.

Despite the heavy casualties suffered, military success in the battle of Tarawa was a huge victory for the U.S. military, because the Gilbert Islands provided the Pacific Fleet a platform from which to launch assaults on the Marshall and Caroline islands, advancing their Central Pacific Campaign against Japan, agency officials said in the statement.

In the immediate aftermath of the fighting on Tarawa, officials said, U.S. service members who died in the battle were buried in a number of battlefield cemeteries on the island.

The 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company conducted remains recovery operations on Betio between 1946 and 1947, but Cooper's remains were not identified then, officials said. All of the remains found then on Tarawa were sent to the Schofield Barracks Central Identification Laboratory for identification in 1947.

In March 1980, the Central Identification Laboratory, a predecessor to the accounting agency, sent officials to Betio Island to receive skeletal remains that had been recovered during a construction project, officials said. Of the three sets recovered, two were identified.

The third was declared unidentifiable and buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

In 2016, the accounting agency disinterred the remains of 94 Tarawa Unknowns from the Honolulu cemetery for identification. The remains were sent to a laboratory for analysis, officials said.

To identify Cooper's remains, accounting agency scientists used dental and anthropological analysis. Also, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome DNA analysis, officials said.

Cooper's name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl along with the others missing from World War II. A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for, officials said.

He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, agency officials said. A date for that service has not been set.

Contact Ben Benton at bbenton@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6569. Follow him on Twitter @BenBenton or at www.facebook.com/benbenton1.