In the shade of the September afternoon, Jerome Meadows sits beside the Walnut Street Bridge, thinking of punch lists. He is thinking of cranes. He is thinking of Ed Johnson.

The product of years of work - the dialogues with his muse, the distillation of research, historical violence and hope into art - was installed this week beside Chattanooga's historic bridge. His work is just days away from becoming a permanent fixture in the history and psychology of the city.

On Sunday, the visual artist from Savannah, Georgia, will reveal his rendering of Johnson, the innocent Black man who was lynched on the bridge 115 years ago, and Styles Hutchins and Noah Parden, the Black lawyers who fought on behalf of Johnson's innocence all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The depiction of the three men - representing grace, courage and compassion - tells both the history of the unjust murder of an innocent Black man and the legal fight that ensued. It also presents an artistic epilogue to the story. That chapter is depicted specifically in the posture of Johnson - his step taking him away from the bridge and out of a noose, his eyes shifted toward the heavens.

"In other words, after all these years, after all of the silence and the disregard and the horror of his actual murder, he's finally walking away from that," Meadows said. "He's finally being free from that."

Meadows's art is the latest rendering of Johnson's story, which has been and is being retold in a variety of mediums - visual art, a podcast, a play and a documentary. Each offers its audience, and the city, a new angle to the story and a different opportunity to reckon with the violence that occurred 115 years ago.

"That's why we have these different forms of communication because the story is so potent that all of these have a way of giving you a perception of it that fills you up that much more," Meadows said.

HUMANIZING HISTORY

Johnson was falsely accused of raping a white woman in 1906 and found guilty by an all-white, all-male jury, despite little evidence and a dozen witnesses who testified he was in another part of town at the time of the attack.

Johnson, who was in his early 20s, was scheduled to be executed, but his attorneys - Parden and Hutchins - appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court placed a stay on the execution and agreed to hear the case. But an angry mob broke into the Hamilton County jail and took Johnson to the Walnut Street Bridge, where they hanged him.

The defiance of the Supreme Court order made national news at the time, and several Chattanooga-area officials were prosecuted and incarcerated. Throughout Johnson's trial and after the lynching, Black residents espoused his innocence and protested against the extrajudicial violence carried out by white citizens of the area.

Johnson's story remained in the psyche of Black residents in Chattanooga. The telling of what happened passed between generations, even as the history faded from the memories of others, notably white Chattanoogans.

The story regained a bit of attention in 1999 with the publishing of "Contempt of Court" by Leroy Phillips and Mark Curriden. Phillips also showed LaFrederick Thirkill, a local school administrator, Johnson's gravesite at Pleasant Garden Cemetery in Ridgeside.

Phillips and Thirkill began traveling the country to discuss Johnson's story, and Thirkill later wrote "Dead Innocent: The Ed Johnson Story." A production was held at Chattanooga State Community College, and Thirkill used the proceeds to launch the Ed Johnson Memorial Scholarship Fund for local students pursuing a degree in criminal justice.

Thirkill created fictional characters in the play - identified as lady one and lady two in the script - to provide the Black perspective of the events, something he felt would supplement Phillips' book, which had focused on the legal battle and impact. He turned to newspaper clippings to get quotes from Johnson and understand how various communities responded.

In another scene, while Johnson is in jail, Thirkill had the protagonist talk to a woman jailed in a nearby cell. This was an opportunity for audiences to hear Johnson process his situation, the frustration as well as the fear.

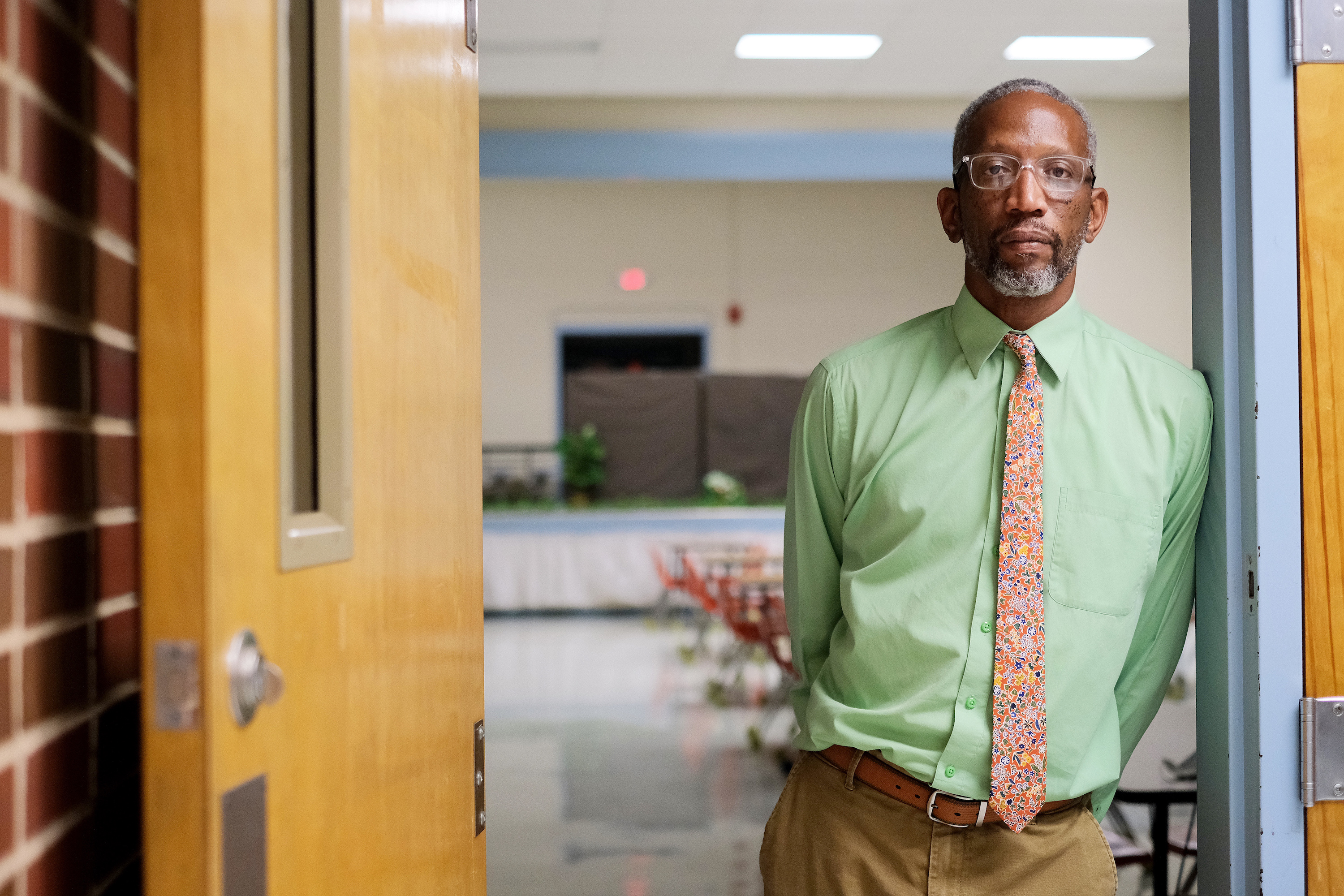

"I just wanted to make sure people saw him as a person as opposed to a criminal or some brute, as he was falsely described in the whole proceedings of the court," Thirkill said.

Staff photo by Wyatt Massey / LaFrederick Thirkill, principal of the Washington Alternative Learning Center, stands in the school on Sept 9, 2021. Thirkill wrote the play "Dead Innocent: The Ed Johnson Story" to raise awareness about the man who was lynched from the Walnut Street Bridge in 1906. Thirkill is a member of the Ed Johnson Project committee.

Staff photo by Wyatt Massey / LaFrederick Thirkill, principal of the Washington Alternative Learning Center, stands in the school on Sept 9, 2021. Thirkill wrote the play "Dead Innocent: The Ed Johnson Story" to raise awareness about the man who was lynched from the Walnut Street Bridge in 1906. Thirkill is a member of the Ed Johnson Project committee.

THE THREE TRAITS

Meadows, the visual artist who was chosen in 2018 to create the permanent memorial, had never heard Johnson's story before learning about the memorial project. He had visited Chattanooga many times before to see friends and had even crossed the Walnut Street Bridge before knowing the full history of the place.

He was particularly struck by Johnson's reaction to the violence and injustice. This is a story that makes you angry, Meadows said, but in Johnson's last moments he looked upon those who would kill him and offered forgiveness.

"The lesson for me was, and it's purely personal, was that these issues, no matter how horrifying and angry they may make you, there's a lesson and there's a journey to be experienced beyond them," Meadows said. "Anger doesn't take you there. Anger locks you into that. This was all sort of theoretical and intellectual until I considered Ed Johnson's words in light of what he had experienced. And so that became the real underlying influence for the design, the spiritual design of the memorial."

Meadows' work emphasized three traits - grace, courage and compassion - embodied by the central characters of the story.

Johnson is stepping away from the bridge and out of a noose. Parden faces the bridge, pointing out the injustice that is taking him to Washington, D.C. Parden is depicted holding a document for the Supreme Court.

Hutchins leans with an outstretched hand toward Johnson, their hands just inches apart but unable to touch. Meadows said the gap signifies the efforts the attorneys went through to find justice and save their client but the ultimate failure of the system to protect Johnson.

Meadows intentionally built the figures to be life-sized, at ground level with their audience. Onlookers can approach the historic figures, potentially seeing themselves in the art or wondering how they would have reacted, rather than other types of statues that are oversized and placed on pedestals, unreachable and almost looking down upon their audiences.

HEARING THE STORY

As Thirkill's and Meadow's renderings present an artistic angle to the story, work has also been done to provide various historical narratives. The first is Phillips' book, which recounts the impact on the American legal system of the appeal from Chattanooga.

Around 2007, local filmmaker Linda Duvoisin began creating a documentary on Johnson's story after reading about it in a newspaper.

The project is ongoing, and a roughly 20-minute cut of the film was used during community conversations about the memorial project. Showing parts of the film while still creating it was a unique experience, Duvoisin said.

"Most times when you're making a documentary, you're not sharing any of the cuts. That's not the normal process," she said. "But I think with this film, I just felt it was more than the actual kind of filmmaking of it or the film, was telling the story and getting people to understand the story."

Johnson's story, from the legal battle to the community reaction, is complex and the documentary format provides the kind of space the story deserves, Duvoisin said.

Last spring, 12 honors college students at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga undertook to tell the story as a narrative podcast. Their professor, Will Davis, had heard of Johnson's story while working on other projects, such as Tennessee Valley StoryCorps and "Stories from The Big 9" about the city's M.L. King Boulevard.

In the second half of the spring semester, the class produced the five-part podcast "We Care Now. A Podcast for Ed Johnson." Each member of the class worked as either a writer, producer or editor on the project. They retold the story of the false charges leveled against Johnson and interviewed key players in the 21st century movement to memorialize the story.

Marcella Rea, a sophomore studying English and political science, said she visited Chattanooga a lot before coming to college but never knew the story of what happened on the Walnut Street Bridge.

Rea has not crossed the bridge since working on the podcast. This has not necessarily been a conscious choice, Rea said, but it just has not happened.

"I feel like when you don't know, it just looks like a big, cool bridge. Then when you do, that's always the first thing that comes to mind when I see it now," Rea said. "It's changed the way I look at that."

Staff Photo by Matt Hamilton / Artist Jerome Meadows smiles as the statue of Ed Johnson is lowered into place Tuesday. Workers from Pointe General Contractors delivered the bronze statues for the Ed Johnson Memorial which weigh about 350 pounds each on the south end of the Walnut Street Bridge on Tuesday, Sept. 14, 2021.

Staff Photo by Matt Hamilton / Artist Jerome Meadows smiles as the statue of Ed Johnson is lowered into place Tuesday. Workers from Pointe General Contractors delivered the bronze statues for the Ed Johnson Memorial which weigh about 350 pounds each on the south end of the Walnut Street Bridge on Tuesday, Sept. 14, 2021.

OVERLOOKED HEROES

One recent day as Meadows sat beside the site of the Chattanooga memorial, a crane some 500 miles away hoisted a 12-ton statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee from its pedestal in the former Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

The artist is thankful the Johnson memorial was in progress before the national debate on which parts of history become memorialized and why those pieces are emphasized reached its fever pitch.

"I feel blessed because the Ed Johnson memorial was sort of ahead of the curve. We're not doing this as a result of those things coming down. This was the leader of that," he said. "I feel emboldened to the extent that I'm not really concerned about things coming down but with building up something."

Meadows supports putting history in context, which could mean removing memorials like Lee's or putting up memorials like Johnson's beside the Walnut Street Bridge.

"It seemed to me that the memorial needed to connect with the bridge because the bridge is where this horror occurred," Meadows said.

The upcoming memorial beside the bridge also brings to light what is perhaps the overlooked part of the overlooked story of Johnson - the two Black attorneys.

In 2018, while digging into Johnson's story, Meadows was frustrated by the national applause for the recently released "Black Panther" film and its depictions of fictional Black heroes. He was frustrated by lack of recognition for real-life Black heroes who courageously faced threats and overwhelming odds, such as Hutchins and Parden.

"What we need as a society, and as African Americans in particular, there's less need for fantastical, fanciful, imaginary heroes and more a need to focus on those individuals, those human beings who are actually doing heroic things," Meadows said.

Thirkill feels a similar frustration. As more people come to learn Johnson's story through various forms of storytelling, he wondered why audiences seem more eager to latch onto the injustice and the victims of a story rather than the heroism of those like Parden and Hutchins.

"Why can't we focus on their successes rather than Ed Johnson's tragedy?" he said.

Contact Wyatt Massey at wmassey@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6249. Follow him on Twitter @news4mass.

Ed Johnson weekend events

To see the description of each event visit edjohnsonproject.com/dedication.Thursday, Sept. 16— Artist Talk: Jerome Meadows: 6 to 7 p.m. at The Hunter Museum of American Art, 10 Bluff View Ave.Friday, Sept. 17— People’s History of Chattanooga Tour with Michael Gilliland: 12 to 2 p.m. and 3 to 5 p.m. at Union Depot Historical Marker, 158 West M.L. King Blvd., near Carter Street.— The Work of an Artist: Q&A with Jerome Meadows: 5 to 6:30 p.m. at The Bethlehem Center, 200 W. 38th St.— The Ed Johnson Project Keynote Lecture and History Roundtable Discussion: 5:30 to 7:45 p.m. at The Camp House, 806 E. 12th St.Saturday, Sept. 18— History Panels on Display: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. at The Camp House, 806 E. 12th St.— Colors of our World Storytime: 10 to 11 a.m. at Chattanooga Public Library — Downtown Branch, 1001 Broad St.— RISE MLK History Tour with Shane Morrow: 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 3 to 4:30 p.m. at Waterhouse Pavilion, 850 Market St.— Medal of Honor Tour: 2 to 3:30 p.m. at Charles H. Coolidge National Medal of Honor Heritage Center, 2 W. Aquarium Way.— The Legacy of Lynching and the Soul of America: A Conversation with Jon Meacham and Eddie Glaude, Jr.: 5 to 6 p.m. at Olivet Baptist Church, 740 E. M.L. King Blvd.— Keeody Gallery Presents: Visuals for the Voiceless: 6 to 8 p.m. at ArtsBuild, 301 E 11th St.Sunday, Sept. 19— The tomb of Ed Johnson and the Resurrection of Christ: 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. at The Hamilton County Courthouse lawn, 625 Georgia Ave.— The Ed Johnson Memorial dedication: 3 to 4:30 p.m. at Walnut Plaza, 100 Walnut St.— The Ed Johnson Memorial dedication gathering: 5 to 6:30 p.m. at Walker Pavilion in Coolidge Park, 150 River St.