Proclaiming itself as the "Most Patriotic City in America," Chattanooga had proven its commitment to supporting the United States Armed Forces during the Great War by raising more than $6 million during the Liberty Loan campaigns. But the city was just getting started.

Almost immediately following the Liberty Loan campaigns, the nation launched its War Savings Certificates program, and Chattanooga signed on. C.C. Nottingham, Z.C. Patten Jr., and T.L. Landress hit the speaking circuit as Hamilton County's co-chairmen, while Chattanooga's T.R. Preston was named state director. Before the armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, Chattanooga and Hamilton County residents had purchased more than $2 million in War Savings Certificates.

While Chattanooga's businessmen were engaged in raising funds to support the troops, the women of the community were equally committed to supporting the war effort. When Congress declared war in April 1917, local women's civic and patriotic organizations began work. Individual women began knitting socks and sweaters. Other women stepped forward and developed a strategic plan to aid the hundreds of troops arriving for training each week while also providing necessities for the troops leaving for military action.

The Chattanooga Chapter of the Women's War Council of America, led by Mrs. J.T. Lupton, joined with the local branch of the National League of Women's Services to support the troops based at Fort Oglethorpe. The Y.W.C.A., the Red Cross and the Daughters of the American Revolution initiated projects aimed at specific unit needs. Mrs. J.L. Lauderbach organized a new program focused on food preparedness and conservation. A Chattanooga group known as the Godmothers, headed by Margaret Ochs, chose locations in Chattanooga near Union Station and at Fort Oglethorpe for reading and rest rooms for the soldiers and then furnished them with "the comforts of home." The Chattanooga Junior League, members of the Travelers' Aid and other groups organized "military canteens" at the railroad depots and even organized the mess sergeants and army cooks, providing aprons, caps and recipes. Mrs. D.P. Montague gathered her friends and regularly "undertook the task of feeding State militia units while they were mobilizing."

As the city united in support of the troops based at Fort Oglethorpe, state and local military organizations eagerly awaited involvement in the fight, and they did not wait long. By early fall of 1917, Chattanooga had said good-bye to Capt. Douglas McMillen and Troop B when they were ordered into camp along with the Tennessee Cavalry, with Col. Perry Fyffe commanding a squadron. Luke Lea was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the First Field Artillery, with Thomas N. McIntyre named as a major in the unit. "There was a general scurrying of military feet in Chattanooga" when the Tennessee guardsmen were "passed into Federal service" under the command of Gen. L.D. Tyson. In an interesting footnote supporting Chattanooga's claim as the "most patriotic city," the Chattanooga Rotary Club "clad and shod all of Battery B" before its departure for combat.

But the city did more than just provide support for the troops. By January 1918, city residents faced scarcities of fuel and food supplies. A coal shortage later that month led to a decision that all major manufacturers, unless providing food, would close for five days and then, following their reopening, would close on Mondays and holidays in an attempt to conserve fuel. "Few attempted to continue business. Offices and even cigar and soft-drink stores were deserted" on those cold days. "It looked as if a plague had struck the city."

The newspapers that year carried stories of food scarcities but also printed stories encouraging "spring gardening" and happily reported the news that "vacant lots everywhere were under cultivation." Sugar and bread became difficult to obtain and, by early summer, allocations of two pounds per person per month were enforced, while restaurants limited patrons to one teaspoon per visit and cakes, pies and cookies disappeared off the menus.

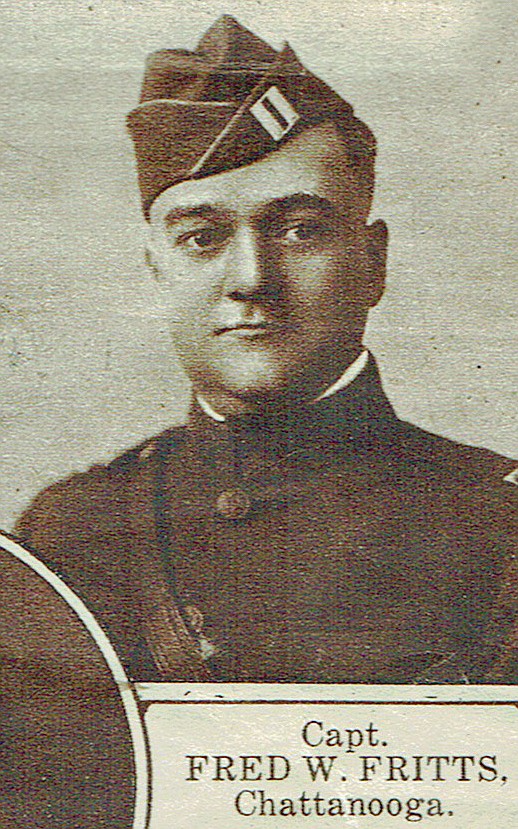

By late summer, news from the Western front replaced concerns about food and gasoline shortages. The Chattanooga community gathered in grief as telegrams began arriving with devastating reports. They mourned the deaths of more than 115 local men, including Lt. Clifford B. Grayson, Lt. James C. Lodor, Lt. Christopher S. Timothy, Capt. Fred Fritts, Lt. Robert G. Buchanan, Lt. Jesse P. Hunt, Capt. Augustine B. Littleton and Chattanooga's first casualty of war, Lt. Davis King Summers.

The Great War was being fought with a cost.

Linda Moss Mines, the Chattanooga and Hamilton County historian, is regent, Chief John Ross Chapter, NSDAR.