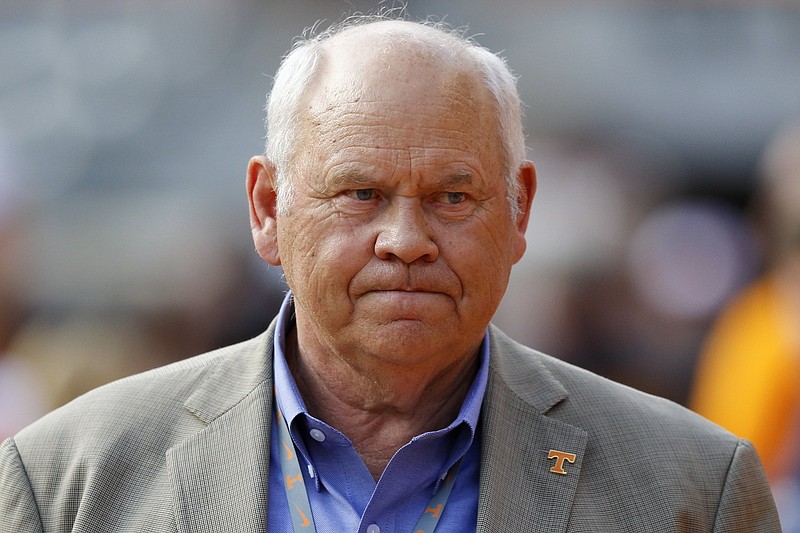

Befitting someone who has always encouraged folks to live in their hopes instead of their fears, University of Tennessee athletic director Phillip Fulmer sounded like a man whose cup runneth over with hope for the upcoming college football season during an interview last week with the Knoxville News-Sentinel.

"I absolutely think that everything is headed in a good direction for us to have this season," he said.

And how many fans does he believe will have a chance to witness the Volunteers' seven home games inside Neyland Stadium?

"We're looking forward to having a season and a full stadium," he said. "We'll adjust from there."

Pressed on the issue of having a full stadium for the Sept. 5 season opener against visiting Charlotte, Fulmer replied: "That's the desire, yes."

It is the desire of every college athletic director in the country this summer. Significant money has already been lost with the nationwide shutodown of athletic departments on March 12 due to the coronavirus pandemic. Adding a fall without football - the sport that funds every other sport at most universities - could prove catastrophic.

Not that Fulmer is guaranteeing that 102,455 Volniacs will be allowed into Neyland for Charlotte or any other home game.

"Circumstances could call for a change of some sort of direction," Fulmer told the Knoxville newspaper. "There's still things on the table. It's not like Coach Fulmer is going to sit down and make a decision (on fan attendance). We're going to make a decision collectively with our experts and the health department and the (medical) task force and the conference."

If it's Tuesday as you read this, we are 81 days away from the Charlotte game. A whole lot can happen between now and then, both good and bad. Will there be a second COVID-19 wave before September? Just how many people can Neyland hold while still practicing social distancing, which, along with the wearing of masks, would seem a must unless a medicine is discovered to combat the virus or a vaccination found to wipe it out.

And let's say you're brazen enough to put 80,000 or so inside Neyland for the opener and half of them come down with the coronavirus as the result of that decision, and a couple of thousand of those folks later die. What then? Are we so certain that can't or won't happen? Are we so starved for big-time college football that we throw all caution to the wind for our long-term health and the health of those around us?

Beyond that, what of the athletes on the field? Athletes breathing on each other, sweating on each other, possibly even bleeding on each other?

What should they think about all this? Test them all you want. Take the temperatures of everyone on the field and in the stands. It's still scary, especially if anyone who slips through the cracks comes in contact with someone who's at a higher risk due to preexisting conditions.

Over the past couple of weeks, ESPN has done a survey of college football players, guaranteeing their anonymity in exchange for their opinions on returning to the field in these uncertain times.

Of the respondents, 62 percent said "Yes," while 11 answered "No," but within those answers came a couple of very interesting responses.

While respondent No. 1 said he'd personally feel comfortable returning, he added "It wouldn't feel right because the amateurism versus the other students. The NCAA has kind of sat back and let this happen when the whole reason they came into place was to protect student-athletes. When we need them most, they're disappearing, so it would be, I think, a stain on the idea of [student-athletes] if we start practicing and playing and living on campus while regular students were at home because it's not safe for them. It would be a weird environment to be in."

Of course, respondent No. 2 said he would have no problem with regular students not returning to campus, noting: "I'd probably be even more comfortable with that being the case, if it's not best for everybody to be back. We'd have a smaller number, that would be really beneficial."

But to return to No. 1, there was a time not so long ago when the position of the NCAA seemed to be that there would be no football, or any other sport, if regular students were not back on campus.

Or as NCAA president Mark Emmert noted May 8: "If you don't have students on campus, you don't have student-athletes on campus. That doesn't mean it has to be up and running in the full normal model, but you've got to treat the health and well-being of the athletes at least as much as the regular students."

Coaches will say the student-athletes are being treated better than regular students. More testing. More precautions. Better medical care if something goes wrong.

But with respect to Fulmer and the notion of a Neyland Stadium filled with 102,455 at any point this autumn, this might be the one time to bow to fear rather than hope, if only to dissuade fears that too many lives could be senselessly lost due to false hope.

Contact Mark Wiedmer at mwiedmer@timesfreepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @TFPWeeds.