I spit out the diaphragm call and rubbed two mosquitoes off my forehead. The gobbler had not made a sound for 30 minutes, and I knew it was over for today. I turned and looked back at my hunting partner, Travis Belcher, and he looked at me with palms upward and shoulders raised as if to say, "What the heck happened?"

We had been dueling with this turkey all morning, and three times he had become fired up with repeated gobbles that led us to believe he was going to walk up and maybe get acquainted (and decently shot). It turned out the gobbler was only toying with our emotions, and each time he would drift off and only offer the occasional see-you-later gobble to keep us interested.

"Well," I thought to myself, "that's turkey hunting!"

If you are a turkey hunter, you know exactly what I mean. Turkeys are always elusive and unpredictable, but this spring seems crazier than usual.

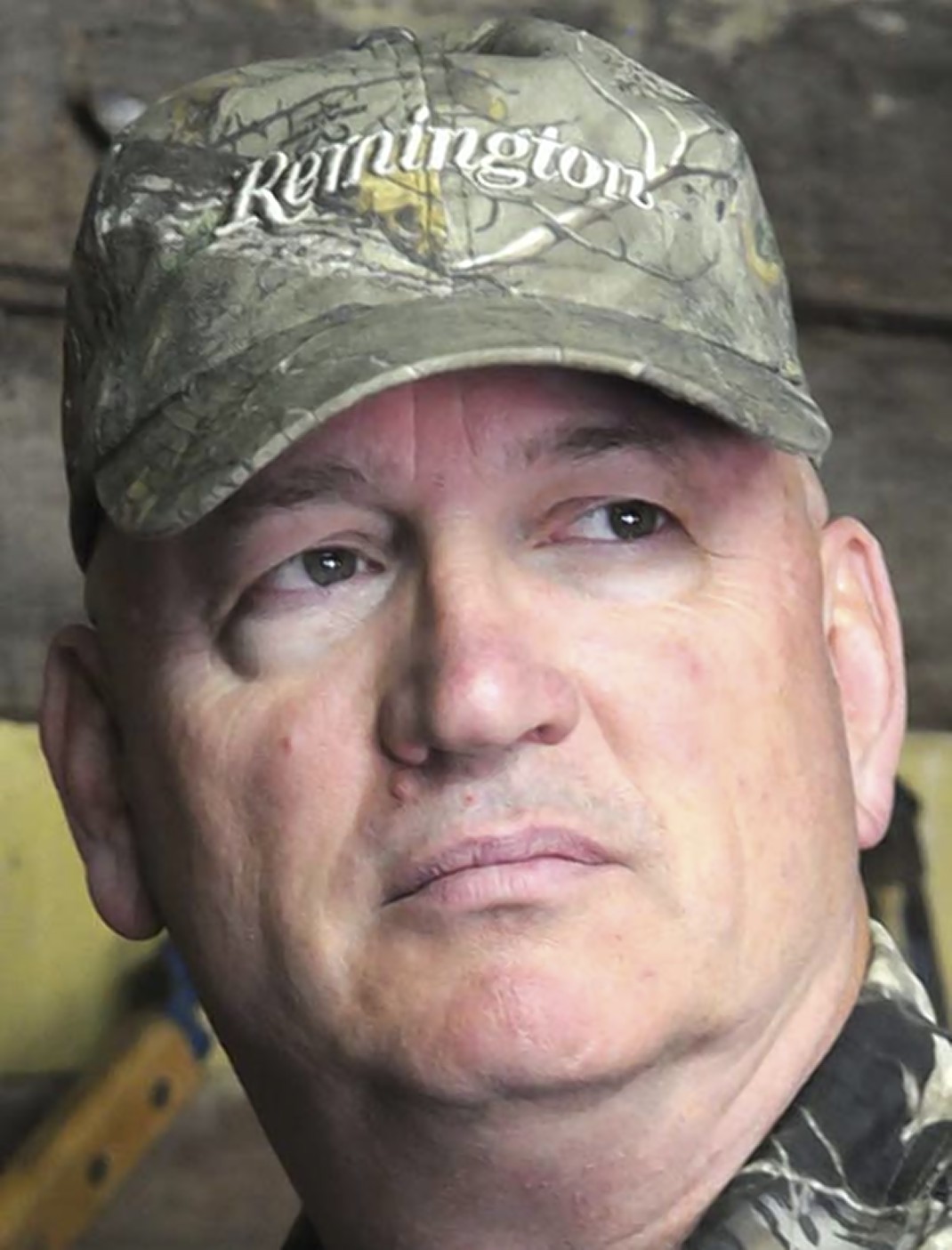

"This season has been pretty tough," said Belcher, the manager for Potts Creek Outfitters, a hunting and fishing guide service in Paint Bank, Va. "We had some success early in the season (his clients took at least 10 birds), but now it is the last week and the birds have been really hard to work - it's been gobble on the roost, fly down and shut up the rest of the day."

Turkey hunters can offer all kinds of excuses and theories on why the birds act like this, and it makes great barbershop and water-cooler fare, but personally I think: That's turkey hunting!

Most parts of the country are in the final stages of the spring turkey seasons, and some states are already done. If you haven't limited out on turkeys, you may be like me and Belcher, staying after these aggravating birds until the last bell rings. When you're worn out from about a month-and-a-half of turkey hunting - footsore, mosquito-bitten and chigger-chomped, plus really depressed from being continually outwitted by a bird with a brain the size of a medium peanut - it is easy to forget how fortunate we are to have as many turkeys around as we do.

The American wild turkey is probably the biggest conservation success story of the past century. Reportedly found in vast numbers when the Pilgrims first jumped out on that rock in 1620, the big birds' numbers declined quickly as the eastern United States was settled. The axe and the saw were probably as much to blame as firearms for lowering turkey numbers, with habitat loss part of the drill with westward expansion.

The early 1900s and into the 1930s and '40s was a dismal time for game populations in America, especially deer and turkeys. America had been in the grip of the Great Depression, but coming out of World War II, things were about to change. New conservation practices were about to take hold, along with new funding sources such as the Pittman-Robertson Act, which allows state fish and game agencies to receive funding from taxes levied on firearms, ammunition and other hunting and fishing equipment.

This was the beginning of a new age in wildlife conservation, and it could not have come at a better time. Seasons, bag limits and other wildlife regulations began to be more strictly enforced, and modern methods of wildlife biology were applied to better manage our game populations, including turkeys. Through it all, it must be remembered that hunters and fishermen of this time gladly funded all of these efforts of wildlife conservation with license sales and monies collected on hunting and fishing gear. (As do today's sportsmen.)

Probably no other tool brought on the restocking and establishment of turkey populations all over the country as much as a little thing called the cannon net. Small metal pipe "cannons" were placed near a baited area with a large, neatly rolled net that was attached to metal projectiles placed in the cannons. When a charge of black powder was touched off electronically, the projectiles shot over the turkeys' heads, trapping them. Game biologists would carefully box up each turkey individually and transport the flock to a new area.

Vast areas were repopulated with wild turkeys this way. Many states had tried raising turkeys in pens and releasing them into the wild, but this was not thought to be successful anywhere. Turkeys raised domestically do not have the right stuff to make it out there.

The wild turkey is now found in 49 states (there is no wild population in Alaska yet) as well as Canada, and there is a group of sportsman who follow the trail to attempt to take a turkey in all 49 states where they're located.

So let us remember as tired and bedraggled hunters how fortunate we are to have the numbers of wild turkeys that we do. Let's also remember that if you are measuring the success of your hunts by how many turkeys you drag home, brother, you need to rethink things a little.

Turkey hunting is getting beat for the fourth day in a row by that old gobbler. Turkey hunting is coming home cold, wet and tired, then saying, "The heck with these crazy birds!" Turkey hunting is also a lot of sunrises you would not have seen, a wonderful morning in the spring woods when you heard more songbirds than you thought possible, and the look on a youngster's face when he hears a turkey gobble for the first time.

Well, that's turkey hunting!

"The Trail Less Traveled" is written by Larry Case, who lives in Fayette County, W.Va. You can write to him at larryocase3@gmail.com.