I stopped writing in cursive about the same time I quit wearing white socks and penny loafers, which is to say, junior high school.

In elementary school in the 1960s, my left-handed scrawl was nearly illegible. I remember pressing down so hard on my pencils - a byproduct of intense concentration - that I broke the points off. My mind wanted to stop and draw each letter, preferably with a straight-edge and a T-square. The idea that handwriting could flow effortlessly, like water across river rocks, never occurred to me.

I was thinking about this the other day as I examined a spiral-bound notebook that my mother filled with family history about 50 years ago. I strained to read her handwriting, not because it was terrible, but because my eyes have grown unaccustomed to reading cursive.

It made me wonder if our sons, now ages 11 and 16, whose cursive writing education was even more brief than mine, will be able to decipher this book of family history 30 or 40 years from now when they might actually be interested in learning about their forebears.

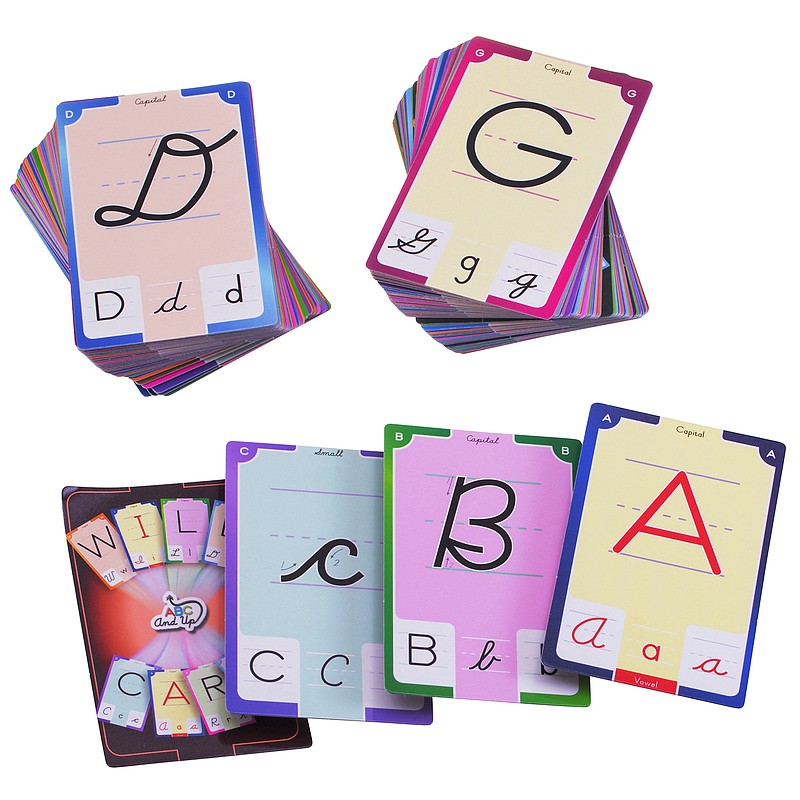

Probably not, says, Rabbi Issamar Ginzberg, a New York marketing expert and one of the inventors of Cool Cursive, a flash-card game (www.abcandup.com, $15) that aims to teach children how to read cursive letters.

"I think that every child should be able to read cursive," Ginzberg said in a recent telephone interview, noting that my kids may someday have to hire an expert to translate their grandmother's "ancient" 20th century script.

That made me laugh because it sounded absurd and also entirely plausible.

"Is cursive important? I believe it is very important," Ginzberg insisted. "It's important for any child who wants to write information and not be connected by a leash to technology."

Ginzberg says the loss of cursive writing mastery was actually the first step on a slippery slope. He worries that younger people will eventually lose the ability to read cursive, and ultimately may even lose the ability to wield a pen or pencil, at all. What happens when the power goes off and our electronic keyboards don't work, he wonders.

To stem that problem, 21 states, including Georgia and Tennessee, have passed laws that mandate children be taught the basics of cursive writing, at least during the elementary school years.

In Georgia, students in grades 3 and 4 are expected to be able to "write legibly" in cursive, according to the Southern Region Education Board. In Tennessee, students are also expected to learn cursive by fourth grade, the SREB says.

We understand the impulse to enforce cursive-writing standards, but it also seems dubious in an era when thumb-typing - i.e. texting - is a preferred method of communication, and many elementary school assignments and tests are conducted online using keyboarding skills, not pencils and paper.

We may be nearing a day when cursive writing recognition is taught more like a second-language skill rather than a practical way of taking notes or writing letters. To think teaching cursive writing to elementary school kids is going to bring back fountain pens and stationery is ridiculous.

View other columns by Mark Kennedy

Ginzberg says his Cool Cursive game is modeled after a learning tool he used to teach Jewish children how to read ancient scripts written by the sage Rashi, who was born in 1040.

"The problem today," Ginzberg says, "is that every time you want to teach a kid something they want to know: What do I need this for?"

The answer, increasingly, may be that reading cursive in the 21st century is simply a way to unlock family secrets and personal letters from the pre-digital age.

Is that enough to ensure that handwriting survives the 21st century?

Probably not.

Maybe the next step in human evolution will be oversized thumbs.

Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645.