As school buses begin their routes and children from kindergarten upward begin their school years, I think of enduring lessons from unexpected sources.

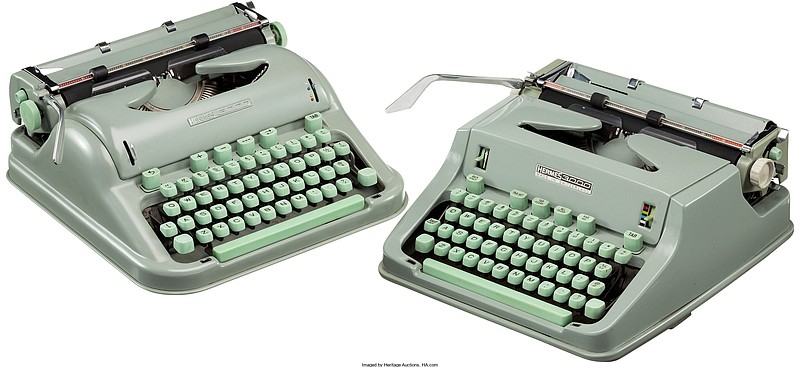

Following the suggestion of a family physician, I enrolled in a typing class in the 11th grade. Knowing of my desire to study medicine, he contended that the only way that a doctor could preserve legible notes was by typing them. The class was taught by a Miss Holliday, a tall, quiet lady of middle years. I was the only male in the class. Each of the girls appeared to share an inborn gift of rapid, correct typing. The keys were unlettered. A chart at the front of the classroom identified each key, but there was no time to use this aid.

Class met daily. We typed increasingly complex exercises. A week passed. Then another. My typing was slow and filled with errors. The fingers of my classmates seemed to fly on their keyboards. My hands were either too big or the keyboard too small. I would never achieve the accuracy and speed, which were needed to pass. I was ready to admit defeat and transfer to mechanical drawing. Miss Holliday called me to her desk at the end of a class. She gave me a folder of poems and short articles and instructed me to type them for the next day. She told me to relax. If I had a radio, I should type to music.

The first batch of assignments took most of an evening. I turned in my work. Another folder followed and then another. My timed, word-counts began to advance. By the end of the semester I had reached an assigned goal. I have been typing ever since, thanks to a teacher who did not give up on her clumsy student in a class of virtuosas.

One year later, Miss Parker, a petite teacher of senior English, introduced me to critical writing. We composed weekly essays, sometimes a book report or short fiction. Red and yellow marks abounded on returned papers. Her comments might suggest another way to express an idea or crisper adjectives. If someone nailed a topic, she might invite the student to read her paper to the class. Perfection was a goal, but no one would attain it. Writing represented a unique opportunity that we should always welcome. She coached us in reading aloud, prose and poetry. "Make it sing." I can hear her now.

Decades ago, the monthly Ladies Home Journal featured a cartoon: "This is a Watchbird Watching You." The bird represented a silent monitor of a child's behavior. Miss Parker is my "watchbird," installed on my shoulder whenever I write.

An anatomy teacher, Dr. T.P.S. Powell, had a unique exercise. He had a duffle bag which contained an array of human bones. The challenge was to reach into the bag, grab a bone and without removing it, name it, describe its connections to other bones, tendons and ligaments. Exercise completed, the bone could be removed from the bag to check its identity. He justified the challenge by describing a scenario in which we might have to examine an injured limb in darkness. Alternatively, lights might fail in the middle of a surgical procedure. I never had to employ this skill. I think I could still identify most of the bones sequestered in a bag and draw a skeleton.

Dr. Torrance, a physiology professor, concluded our first tutorial with encouragement that I attend a concert performance of "The Marriage of Figaro" to be performed the following weekend at a community theater. Despite the intensity of medical studies, he contended that I should not allow work to usurp all of my time. That unique bit of advice led over subsequent years to countless hours of listening to beautiful music, a regimen without side effects or insurance forms.

The four teachers are long deceased. Their lessons persist.

If you have a special memory related to a teacher who is still alive, why not drop her or him a note of appreciation?

Email Clif Cleaveland at ccleaveland@timesfreepress.com.