Tennessee's first shipment of COVID-19 vaccine is expected to arrive at 27 hospitals across the state around Dec. 19, and those most at-risk from the serious and deadly COVID-19 infection will begin to access the revolutionary new drugs.

Having a safe, effective vaccine on hand is a significant milestone and much-welcomed good news as the rapidly-spreading coronavirus that's so far killed nearly 270,000 Americans and more than 1.5 million people worldwide shows no sign of slowing. But public health experts know that injecting two doses of vaccine into the bodies of 4.8 million Tennesseans - how many people it's estimated need to be vaccinated in order to ultimately control COVID-19 - will not be easy.

"If we don't get about 70% of the population of Tennessee vaccinated against COVID-19, we don't stand a whole lot of a chance of moving beyond where we are right now with masks and distancing and holidays away from loved ones," Dr. Michelle Fiscus, medical director for the vaccine-preventable diseases and immunizations program at the Tennessee Department of Health, said during the state's COVID-19 Health Disparity Task Force meeting Thursday.

She said that although distributing COVID-19 vaccine will be a major undertaking for the department, it's something that officials have long anticipated.

"We have exercised for years the ability to vaccinate large numbers of individuals expecting what we thought would be a pandemic flu. It ends up that it's a pandemic coronavirus, but we know how to do this," Fiscus said.

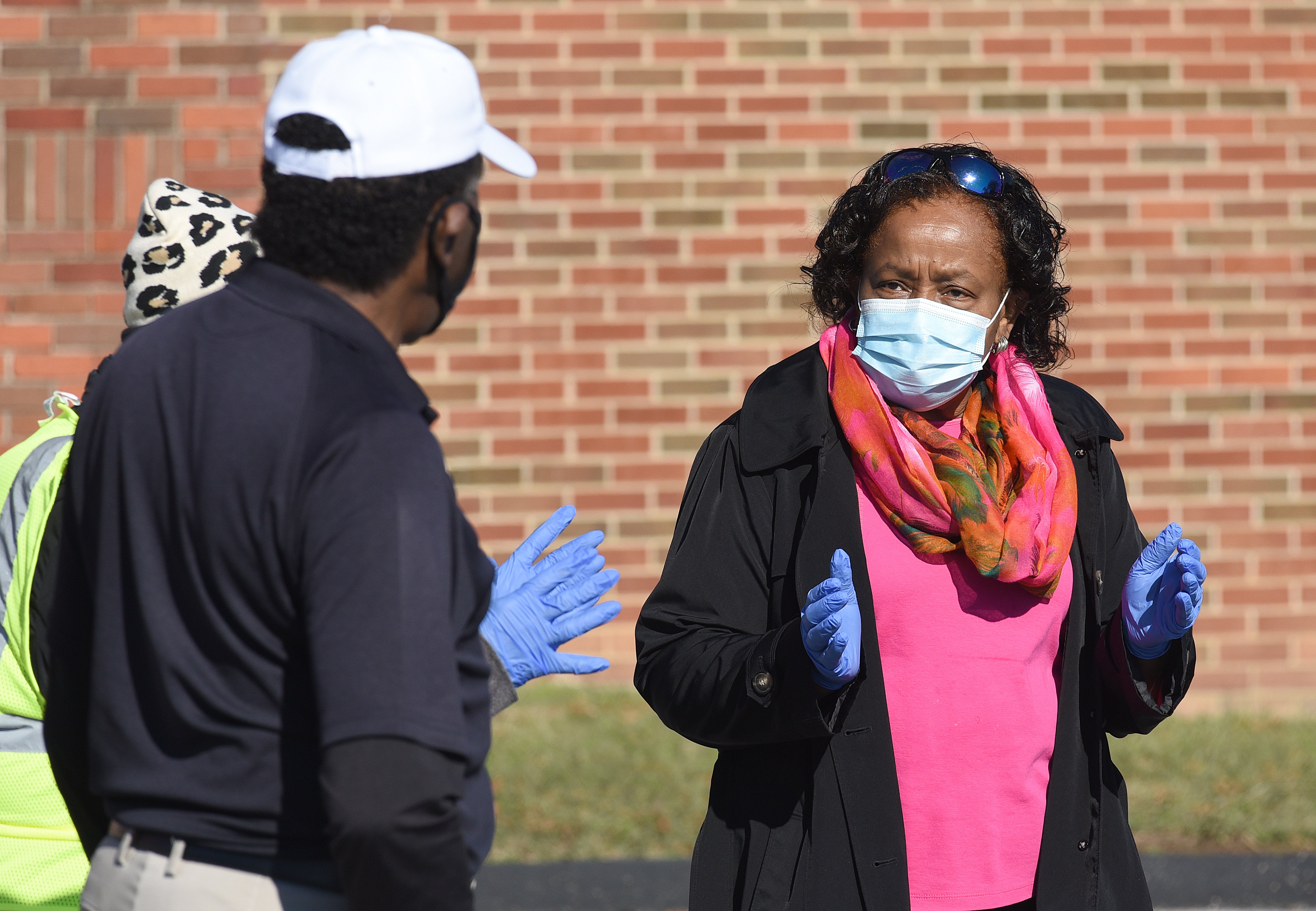

To accomplish that goal, state and local officials will need to navigate complicated logistics, unexpected challenges and inevitable supply shortages. They will also be monitoring who gets the vaccine, tracking outcomes and trying to reach underserved populations with longstanding distrust for the health care system - all while educating the public that getting vaccinated is in their best interest in the face of rampant misinformation on the internet and a raging pandemic.

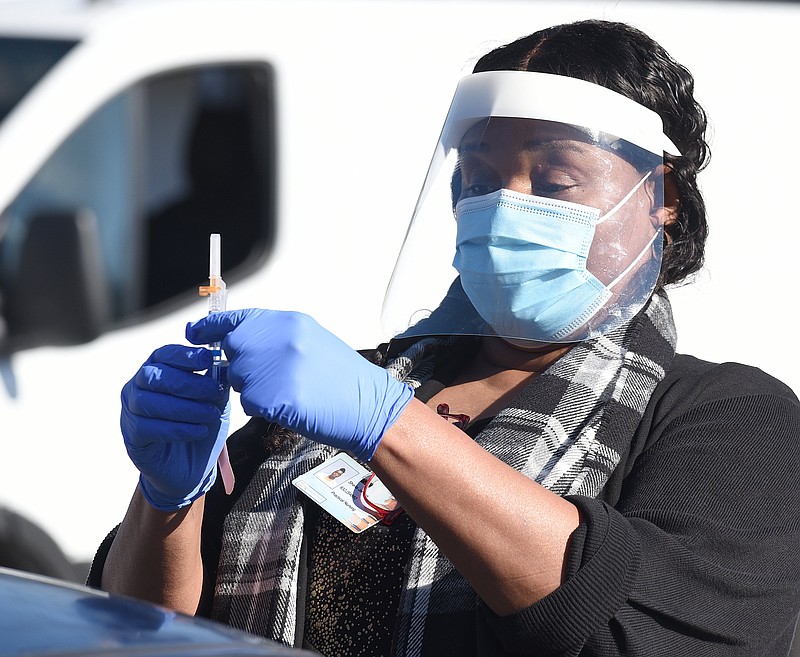

"Vaccines are one thing. You got to get them in arms," said Mary Lambert, an advanced practice nurse and professor of epidemiology and public health policy at the Vanderbilt University School of Nursing who used to work at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"This is so different, just because of where we are in time and the social media aspect that influences so many things. The trust that individuals have in scientists and health care providers has been eroded just a bit," Lambert said. "We've got some work to do. I'm most concerned about getting the messaging out there - how we do that, who's going to do that, and how soon we can get started? We probably should have started yesterday."

Fiscus said that the name "Operation Warp Speed" - the partnership between the federal government and the private sector to accelerate development of COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics - works against those tasked with instilling confidence in the safety of vaccines. However, people need to understand that the scientific process for developing these vaccines was not rushed, she said.

"This is the same scientific process that we use for measles and mumps and chickenpox vaccines," Fiscus said. "What changed is that the manufacturing side has happened alongside of the science."

When drugs are developed under normal circumstances, Fiscus said they go through three phases of clinical trials in order to evaluate safety, effectiveness, side effects and outcomes. Then, funding the mass production process begins.

"This process can take years, especially because the risk part of this is in the manufacturing of these vaccines, and it can sometimes be very difficult to raise the capital to manufacture vaccines," she said.

In the case of Operation Warp Speed, the federal government took on that financial risk and began scaling up manufacturing from the start, so that when the research side was complete and the vaccine made it through all the safety checks, it could be immediately deployed.

Fiscus said Tennesseans can find additional comfort in knowing that by the time the first vaccine reaches the state, millions of people will already have received it because Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine has already been approved in the United Kingdom with the first round of shipments on the ground.

"Which puts us at some nice advantage to be able to look and be further reassured from the data coming out of the United Kingdom that these vaccines are going to be safe," she said.

R. Alta Charo, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, said during a webinar for science journalists last week that state and local officials need to anticipate confusion with the rollout.

"Officials have to be really open and transparent about why some groups go first and another doesn't, how they're making these decisions, and then, crucially, that these are not fixed in stone," she said. "These will change as new vaccines come online with different profiles for risk and benefit for different groups, as we see outbreaks here and there ... we need to recognize there will be change, and change doesn't mean we were wrong. It means that we are adapting on the fly as the situation changes, which is what a responsible health department would do."

After the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued new vaccination allocation guidance last week, Tennessee revised its distribution plan by moving up residents and staff in long-term care facilities, which have been hit especially hard by the virus.

(READ MORE: Infection rates soar at Hamilton County nursing homes as COVID-19 surge continues)

Fiscus said that she expects it will take "the better part of 2021" before vaccines are widely available for all Tennesseans, so even after they arrive, residents should prepare to keep social distancing, wearing face masks and avoiding crowds.

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or follow her on Twitter @ecfite.