EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is the first of a two-part series. Read part two here.

In 1978, Johnny Hale began honing the skills needed to become a flight nurse and one day land his dream job on the air medical team for Erlanger's Life Force air ambulance program.

Growing up in North Georgia, Hale learned that Erlanger - the Chattanooga-based public hospital and academic medical center - was "the place to be" for trauma care. After a decade working on ambulances and pulling 12-hour shifts in the emergency department and intensive care unit at another hospital, Hale joined the health system in 1988 as one of the original crew members for Life Force.

But like many longtime employees, securing a job at Erlanger for Hale wasn't just about doing what he loved for a living. He wanted to build a dream life for himself and his family to enjoy long after his days in health care.

"It was a big deal, and they had good benefits," Hale said. "The pension plan was part of that, to make it a destination job, and that's what I intended for it to be - my destination job. All of those things played into [helping] make my decision to go to Erlanger."

Then, on Sept. 24, 2020, the Erlanger Health System Board of Trustees voted during a public meeting to immediately suspend lump-sum payments from the hospital's pension plan in an attempt to shore up the plan after decades of chronic underfunding. Every other resolution presented that evening was listed on the meeting's agenda except for the one concerning the pension.

(READ MORE: Erlanger board's recent pension vote may have violated Tennessee open meeting law)

"They threw that on us just out of the blue, and it was like somebody dropped a rock on me," Hale said. "They didn't give any options, like if you've already applied [for retirement] or 30 days notice. It was immediate."

Staff photo by C.B. Schmelter / Former certified flight registered nurse Johnny Hale poses outside of his home in Rossville, Ga. Hale was an original member of the Erlanger Life Force Air Medical crew. Now retired, Hale said he felt like he was "slapped in the face" when he heard the news that Erlanger Health System was suspending pension benefit lump-sum payments for retirees.

Staff photo by C.B. Schmelter / Former certified flight registered nurse Johnny Hale poses outside of his home in Rossville, Ga. Hale was an original member of the Erlanger Life Force Air Medical crew. Now retired, Hale said he felt like he was "slapped in the face" when he heard the news that Erlanger Health System was suspending pension benefit lump-sum payments for retirees.Trustees acknowledged that the decision was painful but said it was necessary in order to stabilize the pension for all participants. About 2,700 current and former Erlanger employees are vested in the plan.

The option for retired employees to receive their pension benefits in an up-front, lump sum is by far the most popular choice, but board members said allowing large chunks of money to be withdrawn from the fund as it now stands is unsustainable. As of June 30, 2020, the pension was only about 36% funded, or about $83.5 million underfunded.

Paula Roark, a 19-year veteran Erlanger employee who had already announced her retirement at the time, said she burst into tears upon learning the news.

"They kept saying they had to protect the plan," said Roark, who officially retired in December. "But my thoughts were, 'Why had no one protected the plan before?'"

Roark, a former manager in the employee health and work force divisions, had put in her retirement notice twice before that September - initially in August 2019 and again in July 2020 - but wound up rescinding it after her boss begged her to stay. At the time of the board meeting, Roark was helping to move her departments to a new location, as well as manage employee COVID-19 exposures, conduct contact tracing and oversee the monumental task of vaccinating Erlanger's roughly 6,000 person workforce against influenza.

"I said, 'As much as I would love to help and get us through these flu shots and this transition, I just can't. My husband's 67 years old, I'm 64. We're very concerned that I'm going to bring [COVID-19] into our home,'" said Roark, recalling what she told her boss in July. "She said, 'Paula, I cannot do this without you.'"

When a co-worker told Hale that the board had voted to suspend the lump-sum, he said his 32 years at Erlanger - 25 of which he spent as a certified flight registered nurse and the remainder as manager for the Life Force program - flashed through his mind. Like Roark, he also had announced his retirement before the board meeting. Hale officially retired in November.

"I've been a loyal, stellar employee and been an ambassador for Erlanger," Hale said. "I just felt like I'd been slapped in the face. It doesn't matter how good an employee you are, how loyal you are to your employer. It's all for nothing."

FUTURES IN JEOPARDY

Most Erlanger employees will never feel the impact of the board's decision. That's because in 2009, the health system stopped offering a traditional pension - known as a defined benefit plan - in favor of a defined contribution plan, akin to a 401(k) program.

Starting in the 1980s, employers as a whole began shifting away from defined benefit retirement plans, which incentivize employee retention, toward defined contribution plans that move with employees when they change jobs. Erlanger introduced its defined contribution plan on July 1, 2009.

Defined contribution plans are always fully funded, because they rely on employees to contribute a portion of their salary and allow employers to decide how much, if any, they contribute to the plan. Those funds are then invested, and employee retirement incomes depend on how well those investments perform.

By contrast, it's the employer's duty to fund a defined benefit plan. Employee retirement income is based on a fixed formula that factors in their salary and years of service. Employers bear the risk if the market fluctuates and must come up with additional funds to cover losses.

These types of pension plans are most common in the public sector, but many hospitals and health systems also offer defined benefit plans - although they, too, are shifting toward defined contribution plans.

In June 2020, S&P Global issued an analysis of 188 not-for-profit hospital pension funds and found that the median funding status was 83% based on data from the 2019 fiscal year - a far cry from Erlanger's 36% pension funding status.

But there is a key difference between many of those hospitals and Erlanger. Because Erlanger is county owned, its plan is public and subject to different rules and requirements, similar to the pension plans offered to state and local government workers.

"Unlike defined benefit plans offered by private companies, state government plans lack both oversight by the federal government and an insurance program to provide benefits if the plan fails," researchers Karen Lahey and Leigh Anenson wrote in a 2007 paper published by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics and Public Policy.

The paper warns that many public plans sit critically underfunded, leaving the financial futures of their beneficiaries in jeopardy.

"A market downturn and an aging population explain the monumental deficit and dangerous financial insecurity of state pension systems," the authors wrote. "Without significant reform, the downward trend can be expected to continue. The growing number of retirees alone will strain the system."

They wrote that although, in theory, the promise of a defined benefit pension puts the onus on the employer.

"In reality, however, the danger that state governments will fail to contribute the funds necessary to finance adequate retirement benefits - the 'funding risk' - falls on the employee," they wrote.

Erlanger's pension didn't fall to such a low level overnight. The sustainability of the fund, which was started in 1964, has been a perennial topic among hospital leaders since the late 1990s.

Trustee Ken Conner, who served as chief financial officer for Erlanger from 1984 to 1997, said during the September board meeting that the option to receive pension benefits in a lump sum was introduced in 1996 based on interest rates and market forces at the time.

Since then, the 2008 recession struck and interest rates dropped from around 7% to 1%. Interest rates are expected to remain low for the foreseeable future, making it difficult for Erlanger to fund its pension through investments.

The Erlanger board acted several times over the years to strengthen the fund. In addition to closing the pension to new hires, Erlanger froze benefit accruals for employees in the pension and shifted them over to the defined contribution plan in 2014. Former Erlanger CEO Kevin Spiegel stressed that employees would have full access to their pensions once they retired.

Still, those moves weren't enough to reverse the downward trend.

Even once a pension plan is frozen, the hospital's obligation to fund that plan could last as long as participants are alive. The average age of active employees in Erlanger's pension plan is about 52.

Recently, Erlanger contributed more to the pension than what's required by actuaries, but funds are being withdrawn at a faster rate than they're going in, Conner said.

After six months of meeting behind closed doors with a select few Erlanger officials - including trustee Jim Coleman and Chief Human Resources Officer Floyd Chasse - Conner said during the September meeting that suspending the lump-sum option was the best - and only - option to assure the pension's viability.

"[The lump sum] is by far and away the preference," Conner said. "If we do nothing tonight, having walked through this and people see what it is, everybody is going to run to announce their retirement and take the lump sum."

Conner went on to say, "I wish I had a better answer ... we looked at everything. Nothing else made any real impact on the plan health. We believe the only way to really get a handle on it is to suspend, temporarily, those lump sums."

STUCK IN THE MIDDLE

The lump-sum option of Erlanger's pension will be restored when the plan reaches 80% funding. Erlanger needs roughly $57.5 million to reach that point.

Trustees hesitated to say how long that would take. However, Conner stated, "if you are not planning to retire in the next seven to 10 years, then the chances are you are going to be able to still get your lump sum."

While that may be welcome news to some, for Erlanger's longest-standing employees closing in on retirement, that dealt a devastating blow to their financial futures in the middle of a raging pandemic.

Hale announced his retirement the first week of September. He expected to receive a $348,000 lump-sum payment when he retired in November and had already requested the paperwork to apply for it weeks before the board's vote, he said.

Now that the lump-sum option is suspended, Hale could take his benefit as a monthly payment - which for him would amount to around $1,800 per month - or risk waiting in hope that he can still get his lump sum eventually.

Participants have until age 70.5 to decide how to receive their funds, and they're locked in once they choose. At 64 years old, Hale may spend six years without his money only to still be forced to take the monthly payment, wasting precious time without his benefits as he ages.

Hale would need to live to be 88 to make the lump sum amount in monthly checks if he agreed to it today, but that money will be worth less as time goes on due to inflation. By receiving his $348,000 earning up-front, he could invest his money and let it grow.

Hale said another major downside of the monthly payment option is that it stops when he dies, leaving nothing for his family. Although there's an option to continue the payments to his spouse after death, the overall payments each month are reduced by 50%.

"The lump sum is the favorite, because once you get that money, it's yours," he said. "The other thing is, that pension plan is not insured. So if Erlanger goes under, I don't get crap. That's the biggest reason, to me, to take the lump sum."

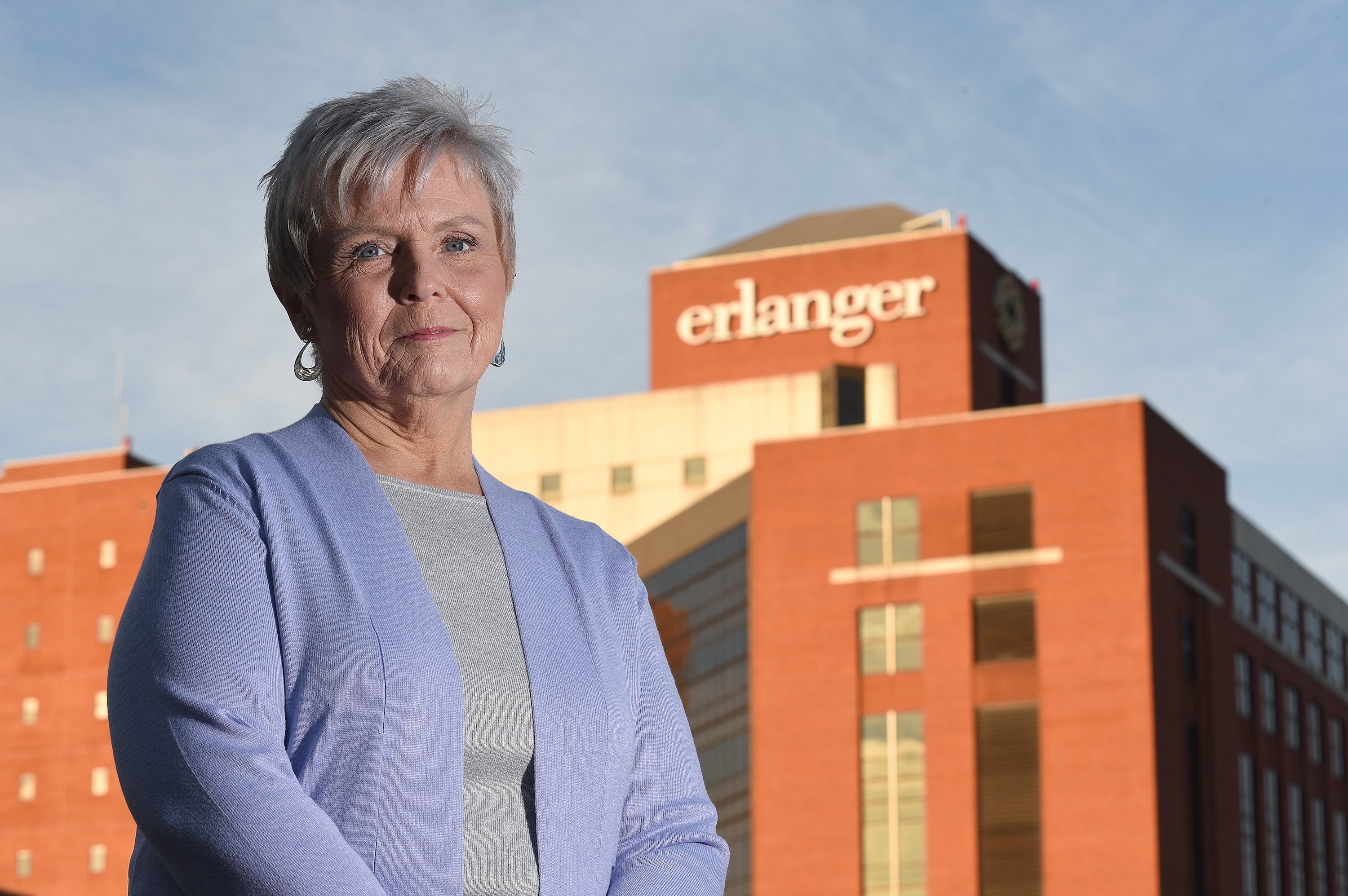

Staff Photo by Matt Hamilton / Paula Roark, a 19-year veteran Erlanger employee, poses outside of Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga. Roark said she frets constantly about her financial future since the Erlanger board voted in September to suspend lump-sum pension payments. Roark officially retired from Erlanger in December.

Staff Photo by Matt Hamilton / Paula Roark, a 19-year veteran Erlanger employee, poses outside of Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga. Roark said she frets constantly about her financial future since the Erlanger board voted in September to suspend lump-sum pension payments. Roark officially retired from Erlanger in December.Hale and Roark had both met with financial advisers and established their retirement plans based on the understanding that each would receive their pension as a lump sum.

Roark's intent was to invest her money and draw off the interest, saving the pension funds if she needed them down the road, she said. Her lump sum would've been about $102,000, whereas the monthly payments would be $533.

"That won't even pay my insurance," Roark said. "I've counted on this, and I wanted to have a comfortable retirement ... now I'm worried sick about making sure we've got enough money to pay our bills."

Roark sent numerous letters and emails to Erlanger trustees and hospital management in an attempt to reverse the decision. She and Hale asked to plead their cases before the board during its October meeting but were told the public meeting was not an appropriate venue to air grievances.

During the board's budget and finance meeting in October, Erlanger officials revealed the hospital's financial performance for the 2020 fiscal year and the first quarter of fiscal year 2021, which spanned July 1 to Sept. 30.

Erlanger reported a $35.3 million net income from operations - which included $55.9 million in federal stimulus funds meant to offset costs of the COVID-19 pandemic - for fiscal year 2020, and a net income from operations of $12.6 million for the first quarter of fiscal year 2021. Erlanger officials touted that performance in a news release after the meeting.

"These first quarter results significantly outperformed budget, and are even more impressive when viewed in comparison to Erlanger's historical first quarter performance," the release states. "These accomplishments, made all the more remarkable in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, national economic challenges, and industry pressures, would not have been possible without thoughtful leadership, decisive action, and the unparalleled dedication of Erlanger associates."

In December, the board approved $7.65 million worth of bonuses and raises for Erlanger's leadership team and staff.

Roark and Hale were stunned.

"One week they're crying poorhouse and saying they can't even fund the pension," Roark said. "Then, a month or two later, they're handing out bonuses because the hospital has done so well. That makes no sense to me."

After the financial reports were released in October, Coleman said, "It would be irresponsible of us to take those funds and fully fund the pension. That would take $80 million, and so we just don't have that capability at this point in time."

The Times Free Press requested interviews with trustees Conner and Coleman for this story, as well as submitted a list of questions to Erlanger officials via email. They offered the following response:

"The Board's presentation on September 24, the corresponding resolution and Mr. Coleman and Mr. Conner's previous statements to the Times Free Press on this point continue to adequately and appropriately speak to Erlanger's actions regarding the pension plan. That is, the Board's actions were both reasonable and necessary measures effected as the Board's effort to ensure that the plan's benefits remain available to all of the plan's [approximately] 2,700 beneficiaries. We would not anticipate commenting further on, but, of course, will let you know should that position change."

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or follow her on Twitter @ecfite.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations and the RRF Foundation for Aging.