Attendance at The Howard School in Chattanooga ebbs and flows with the weather. On cold, rainy days, more children come to school. But on warm days, days suited for outdoor labor, more chairs are empty.

"When the weather's better, they (the students) have opportunities to work," English as a new language coach Jose Otero said in an interview. "Roofing. Construction. Whatever it may be. Landscaping jobs."

Howard is home to Hamilton County Schools' largest population of high-school-aged migrant students. The majority come from the Western Highlands of Guatemala, an area lush with green mountains and crippling rural poverty.

Most of the students come to Chattanooga with the equivalent of a fifth grade education and speak little to no English.

Please click here to upgrade to a newer browser.

Otero refers to their school experience as "interrupted," and for these teenagers — unlike their younger counterparts who haven't had a six-year gap in schooling — convincing them to stay in school, instead of dropping out to work, is a challenge.

"That kid is going to have a really, really, really hard time to be able to make four years at a high school in a new country with a new language," Otero said. "The odds are super against us. When that kid turns 18 years old, he's going to go work, because that's his No. 1 priority."

As the number of newcomers continues to grow, officials are now faced with finding solutions to keep migrant students in school.

"They tell me that a diploma is not enough," Otero said. "They ask for things like legal guidance, immigration help. They ask for driver's license IDs. The incentive, the golden carrot that we dangle, has to be way bigger.

"But the odds are against us," he said, again.

RAPID GROWTH

Since 2017, the percentage of English learners at Hamilton County Schools has nearly doubled from 6% to 11%, according to state data.

While there are 112 languages represented at the district, the majority of newcomers are from Spanish-speaking backgrounds.

To accommodate, the district unveiled its International Welcome Center two years ago to help families navigate the enrollment process and connect them to services and resources.

"We set up the International Welcome Center in October of 2021 knowing that we had an influx of kiddos joining us in the district," Director of English as a New Language Program Diego Trujillo said in a phone call. "And at that point in time we had well over 150-plus kids that had joined us at the Welcome Center."

The district has now enrolled 250 families from over 20 different countries, Trujillo said.

"When we think about families coming to us, I think first off through the lens of the assets they bring," Trujillo said. "Thinking about more specifically, the language and culture and diversity that they can share with us here. We learn a lot daily. And we're very thankful for the opportunities to be able to serve our families. With that being said, though, language sometimes is a challenge."

The district provides various supports including a telephonic line that can connect speakers to over 200 languages for translation purposes.

But despite the district's efforts to overcome language barriers and provide an education, English learners have the highest dropout rate of any student group, 20.7%.

Chronic absenteeism is also high among English learners. Students become chronically absent if they miss 10% or more of days enrolled in school. Districtwide, 16% of English learners are chronically absent. In grades 9-12, that rate nearly triples to 40%.

At The Howard School, where more than one-third of enrollees are newcomers, chronic absenteeism leaps to 51%.

"There's three reasons why our immigrant students miss school," Otero said. "No. 1 is work. No. 2 is they have to stay home and take care of siblings or take care of home situations. And then the third is they're constantly going to help translate for their family members."

And Howard is receiving more newcomers every day. Otero estimates that since the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, he's enrolled at least 140 newcomers.

"The question has become, how do we get these young adults to stay in school?" he said.

TWO CITIES

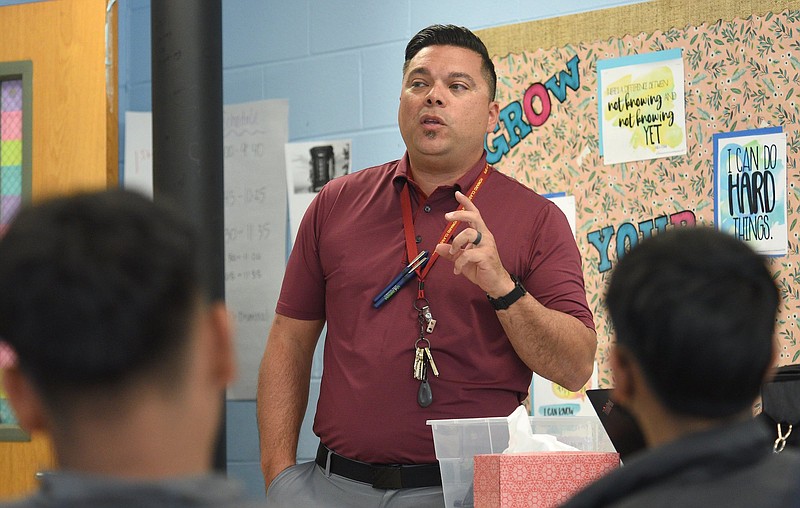

Otero stands in front of a 10th grade newcomer math class and asks in Spanish how many came from one of two cities in the Western Highlands of Guatemala.

"San Marcos?" he asked. Half the hands went up.

"Huehuetenango?" The remaining hands raised.

"The reason why they come from those areas is because it's the most rural areas, but it's also the closest to Mexico, so it's easier to come to America," Otero said. "They're the most impoverished areas of Guatemala. Those are the students that we are receiving."

He then asked the class how many attended school in Guatemala beyond fifth grade. A few students said they had, explaining that after fifth grade, there is a charge to attend school and to get uniforms and supplies, and only the wealthy can afford it.

For many, Spanish is not the language they speak, Otero said.

"Guatemala has 27 to 33 dialects within the country," Otero said, "So, when they come, for some of them, Spanish might be their second language. Not for all, but for a majority of them it is. They speak their dialect at home. And they learn Spanish at school."

That realization prompted Hamilton County Schools to change the name of its English learning program from English as a second language to English as a new language, Otero said.

"These kids that come from Guatemala speak already two languages," Otero said. "So, it wouldn't be a second language, it would be English as a third language."

In Spanish, Otero asked the students how they like education in the U.S.

"They like it, but it's way different," he said translating and summarizing the students' responses. "In Guatemala, if your teacher is mad at you, or you did something wrong, they will yank you up by your ear in two seconds."

In Spanish, Otero asked the children what their education goals were.

"Most of them say to learn English," he translated.

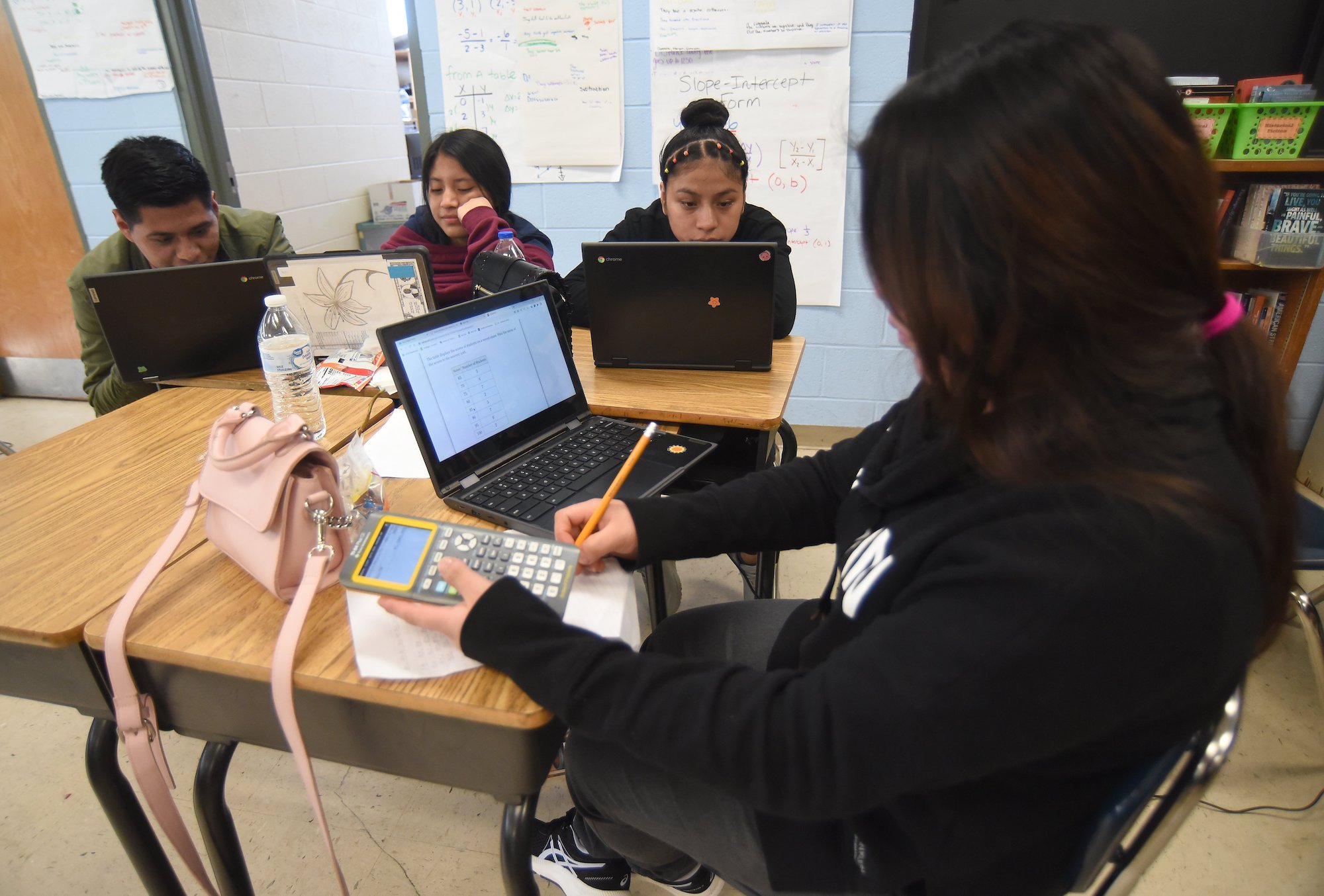

Staff photo by Matt Hamilton / Newcomer students work in class at the Howard School on April 12.

Staff photo by Matt Hamilton / Newcomer students work in class at the Howard School on April 12.

ALL FRESHMEN

When a newcomer arrives at Howard for enrollment, no matter their age, they are always enrolled as freshmen, Otero explained.

In the U.S. a student may remain in high school, regardless of their immigration status, until they are 22 years old.

"They have to take (English as a new language) classes, basic math classes, history, science and all those classes," Otero said. "For the most part, we try to provide an (English as a new language) assistant, someone in that classroom, predominantly for math and science, that is bilingual. You have to have someone in there to help us facilitate the language. And we have that, but we don't have 100% of our classes covered."

Otero explained that when children come in as unaccompanied minors, they are in the custody of the United States government. They will stay in border houses until a next of kin in America responds and signs a responsibility agreement of custody for that minor.

One of the requirements of this is that they attend school as long as they are minors, but after they turn 18, it is their decision. However, unless a family can fully financially support themselves and their high-school-aged child, Otero estimates that 50% of newcomers who turn 18 in the first two years of attending Howard will drop out.

"They see it (graduation) as too far," he said. "The diploma is just too far out of reach."

There are some legal incentives, however, Otero said. Part of his job is to work with migrant families, connect them with the resources they need and hopefully convince them to allow their child to stay in school.

"The biggest incentives that we have are legal incentives," Otero said.

But the pressure to make money is often too strong.

"They will most likely leave school at the age of 18 to work to provide and send money to their families in Guatemala," Otero said. "But not only that, but also help with the bills and the rent here in America. I have seen that the Guatemalan families that are the most supportive, that are the ones that can handle the pressure financially, these students will stay. But that is incredibly rare."

WHY CHATTANOOGA?

Guatemalan influence can be seen in the emergence of several Guatemalan grocery stores, markets and restaurants on Rossville Boulevard in Chattanooga's Southside.

They're shops frequented by many students attending The Howard School, Otero said.

"They can get food that is from their native country, they can get candy and juices and sodas that are predominantly from Guatemala," Otero said "And the reason why they come to Chattanooga is because, where there's places of opportunity, where there's places that have affordable rent, where they have plenty of jobs, where they have local businesses and shops and restaurants that cater to their culture, they come."

Staff photo by Matt Hamilton / A worker at a Chattanooga-area Latino store stocks the shelves on April 13.

Staff photo by Matt Hamilton / A worker at a Chattanooga-area Latino store stocks the shelves on April 13.

The road for immigrants is long and hard.

"Immigrating causes trauma," Lily Sanchez, communications and development manager for La Paz, said in an interview.

La Paz is a nonprofit dedicated to supporting Chattanooga's Latino community by providing services, resources and educational opportunities.

In the past year, the organization has been looking at ways to better connect with immigrant and Hispanic students at Hamilton County Schools.

"As La Paz has evolved, over the years, we have tried to implement more proactive approaches," Sanchez said. "That's where our work with Hamilton County Schools, and particularly the Latino students, comes in. We brought on a staff member to focus specifically on building relationships with Latino students, so that we can identify needs that they are worrying about, needs that they have right now, needs that they feel like they'll have in the future."

She said this builds trust with them.

"That really helps us to validate their experiences," Sanchez said. "Validate the trauma that they may have encountered in their life."

La Paz is looking at ways to instill awareness of the importance of high school and how to effectively communicate that message to immigrant families.

"We are really focusing on building an education for families as a whole around the importance of finishing high school and going on to pursue, whether that's higher education, whether that's trade education, to be able to start the cycle of this upward mobility that a lot of our families have little understanding of, or they placed little value on it, because it's just not the background that they come from," Sanchez said.

She said the most important aspect of convincing students and families to stay in school is representation.

"We've seen that the families are at least more open to considering different options when the information is coming from someone who understands their background, or at least speaks a language that they speak," Sanchez said. "It is definitely not as simple as that. But the more established the community becomes, I think the more they will kind of propel themselves in that direction."

Otero agreed with Sanchez.

"Newcomers have to have a social-emotional education as well as learning English," he said. "The reason why is because when these students come from Guatemala, their transition from Guatemala to America can be very traumatic for a lot of them being removed from their homes."

But he said the most successful way to ensure immigrant students complete high school can only come from changes at the state and federal levels.

"If they could work while they're attending school, and make money for their family, kids would stay," Otero said. "But they do not have a Social Security number, and many are undocumented. Give students work permits, jobs, driver's licenses and a step to residency. Equate 'diploma' to 'citizenship.'"

He said that regardless of a child's undocumented status, success matters.

"The reason why we should care is because whenever there's a growing, prospering, community, growing, developing, a beautiful city like Chattanooga, there has to be a workforce that we can depend on, to help with infrastructure, to help with construction, to help with working in restaurants," Otero said. "A thriving economy survives on a thriving workforce. And in Chattanooga, Tennessee, the reason why it's growing and the reason why it's developing so well is because of our immigrant workforce."

Otero's voice cracked and he covered his face with his hands. He sobbed quietly for several moments.

"My parents were immigrants, and they were given an opportunity to allow me to be educated, and now it's my turn to help them," he said, gesturing toward the class of newcomer students. "They are part of a growing, successful community."

Contact La Shawn Pagán at lpagan@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6476.