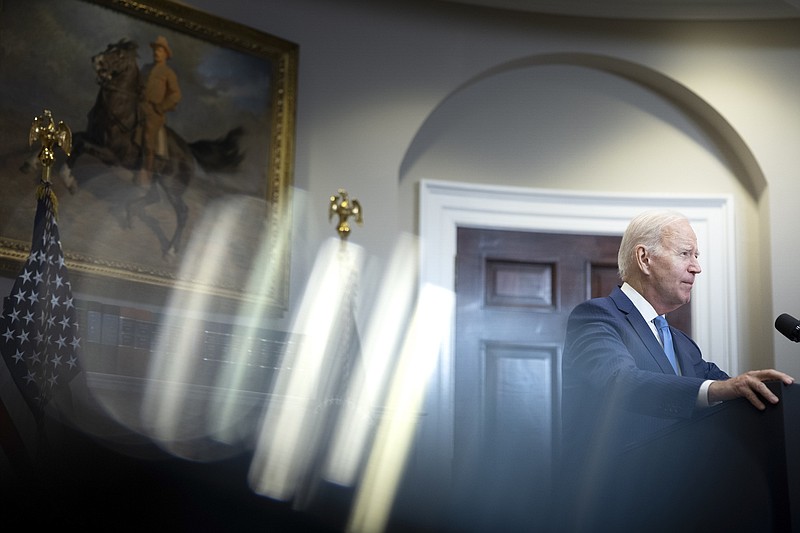

If Congress fails to raise the debt limit, can President Joe Biden somehow borrow more money to save the United States from default? The short answer is no. But that hasn't stopped a group of Senate Democrats from urging Biden to act unilaterally by invoking the Fourteenth Amendment.

The stand-off between the president and Congress over the debt ceiling has revived interest in a little-known provision of the Fourteenth Amendment that says the "validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law ... shall not be questioned." That statement, on its face, does require the government to pay its debts. But it doesn't allow the president to ignore the law passed by Congress that caps borrowing.

The Constitution puts Congress squarely in charge of both borrowing and spending. The validity of the public debts clause doesn't magically allow the president to violate this most basic element of the separation of powers.

This isn't the first time we've had a debate about the underlying constitutional question of whether the Fourteenth Amendment renders the debt limit somehow unconstitutional. And it's understandable why. When a president faces a Congress not controlled by his own party, he'll look for leverage against lawmakers that want concessions in return for raising the ceiling. Even if the president never actually invokes the clause (no president has), the argument can enhance the president's negotiating position.

But it's important to remember that the whole reason the Constitution gave the spending and borrowing powers to Congress was to ensure a separation of powers between Congress and the executive branch. That separation was intended to let the political process, not the will of one person, determine how the country borrows and spends money.

If the president could unilaterally ignore the debt ceiling, he would be able to borrow money without congressional approval. That's a short step from being able to spend money without Congress — another violation of the basic constitutional scheme.

In practice, it is extraordinarily unlikely that the Biden administration would invoke constitutional grounds to ignore the debt limit. So why bother to consider the question, especially since it's hard to begrudge the administration any tools that would help it fend off the madness of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy's threat to force the country into default?

The answer is that too much loose talk about the president's ability to ignore Congress is bad for the separation of powers — and therefore bad for constitutional stability.

Remember when President Donald Trump wanted to build his border wall even though Congress had refused to appropriate money for it? That showdown also represented a threat to the separation of powers.

Trump, too, had a sort of constitutional argument. He claimed a national security interest and invoked his powers as commander in chief. That claim was illegitimate. The president can't spend money on things Congress has refused to authorize.

With Trump campaigning to retake the presidency — and still spreading lies about his 2020 election loss — I'm hard-pressed to think of a worse time for liberals to embrace such a sweeping view of presidential power.

The obligation to pay the government's debts lies with Congress — where the framers put it. If McCarthy decides not to pay the nation's bills, there's nothing Biden can do about it.

Bloomberg