As long as there are letter grades given in schools, there will be students saying the grades don't represent how hard I worked, how hard I'm trying, what I have to live with at home, what advantages I don't have or why I can't learn the way she can.

The same is true with a state plan, now seven years old, of evaluating individual public schools with letter grades.

What state education officials heard last week during a public town hall at East Brainerd Annex was no different from what was said after a state law was passed in 2016 — following a federal directive — requiring the letter grades.

From the beginning, it was emphasized that grades would not be based solely on the academic success of the school but would take into account, among other things, growth in academics, those considered underserved students, disabled students, student readiness for college or the workforce, absenteeism and English language proficiency.

Still, last week a Hamilton County Schools official was saying as a parent, "it is not helpful for me to have a grade that is simply on how the overall proficiency of a school is," and a Cleveland City Schools official was saying he doesn't want the "system [to] not just be a judge of the poverty level of a school or a system and instead actually reflect the work that is being done in those schools and systems."

Unfortunately, too many people today don't want a measuring stick. They don't believe letter grades or standardized tests, or heck, even the subject of mathematics itself, are fair because all people are different and often learn differently and don't have the same home lives.

Others have taken that argument further, suggesting many laws should be abandoned, police forces disbanded and judgments of one person over another ended.

We would argue that's not how America became the country it is.

If schools and school systems don't have standards, how would we measure what students learn, how much they're improving and whether the school is adequately preparing students for life beyond K-12? How would we know whom to hire as a rocket scientist, as an accountant or as an epidemiologist?

We would agree, however, that a letter grade can never be the be-all, end-all for a school. After all, we fully believe that students can attend a poor performing school like Brainerd High School and get a good education if they're motivated to do so and other students can attend a high-performing school like Chattanooga School for the Arts and Sciences and do poorly if they don't put in the work.

That's why, at least according to state officials, schools won't be graded solely on one particular aspect.

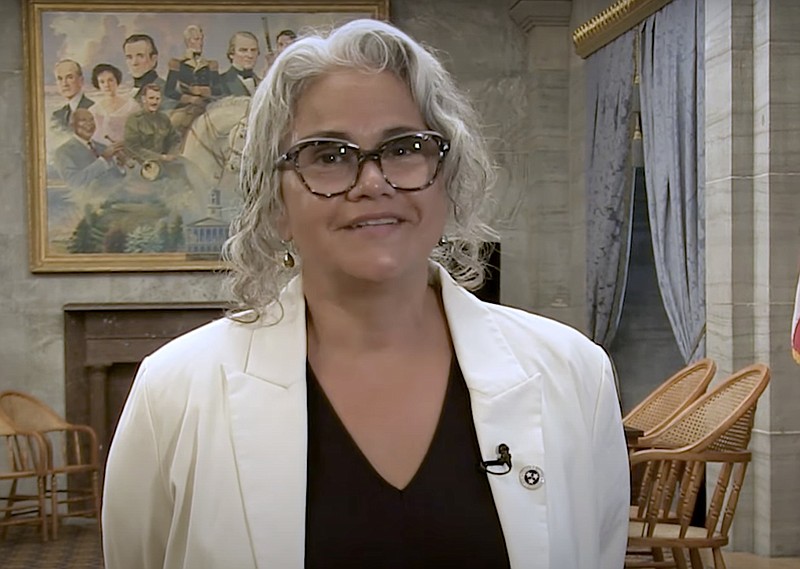

Lizette Gonzalez Reynolds, the state commissioner of education, expressed at the town hall a little surprise — at least it seemed to us — that the impression still existed.

"I've been perplexed with some of these conversations about how only the high-income schools are going to get the A's," she said, "and that is just not the case. That is not the intent of this system. It is about being knowledgeable about what's going on in that campus and whether or not the job is being done to educate those students. That includes growth. Absolutely. But you cannot base a system — tell parents in the face — that their school is doing really well and their kids cannot read."

In February 2018, with the letter grades set to be published after the 2017-2018 school year, the Hamilton County Board of Education voted 7-2 to approve a resolution calling on legislators to overturn the A-F grading system.

What effect the resolution had is unclear, but online standardized testing problems and then the pandemic prompted the state to continue to push back the release of the A-F grading system.

Now, the state is again doing what one of Reynolds' predecessors, Candice McQueen, said the department was doing when the local school board passed its resolution in 2018.

"State law requires the department to publish ... grades ..., and federal law also requires us to meaningfully differentiate among our schools," she said in a statement. "Knowing these requirements, we have sought feedback from thousands of Tennesseans on how to establish this system in a way that is fair and that helps families understand how their child's school — or their future school — is performing. We continue to welcome feedback."

Indeed, the department still welcomes feedback — at schoollettergrades@tnedu.gov — until Sept. 15.

We would hope district administrators, teachers, parents and students come to see the grades, should they be implemented, for what they are — a benchmark and not a death knell for a school or a facility to avoid like the plague.

Indeed, a student's education is surely affected by what's going on at home, by the quality of instruction and somewhat by the school itself. But it's more affected by the students themselves, what they are willing to invest in their education, and how much their parents or guardians are willing to help ensure that investment.

Meanwhile, we need to stop being fearful of measuring sticks.