When he was growing up in Central Florida, Joel Tippens would hop into his dad's 1968 Chevrolet El Camino and the two would drive into the woods to forage for ferns. Tippens' dad was an inveterate gardener — he loved roses — and he insisted young Joel learn the ways of nature, too.

Joel Tippens, now 67, says those boyhood memories are the reason his hands are still drawn to dirt like a dowser's branch to underground water. Tippens says he has had lots of careers — sailor, firefighter, forestry worker, landscape artist — but he keeps circling back to urban farming as his home base.

(READ MORE: Local man is planting seeds for urban micro-farms.)

Today, Tippens is the founding director of City Farms Growers Coalition, a Chattanooga nonprofit dedicated to helping urban gardeners start and maintain vegetable gardens on small patches of dirt, parking lots, school yards, homeless camps — anywhere there is a need for fresh, wholesome food.

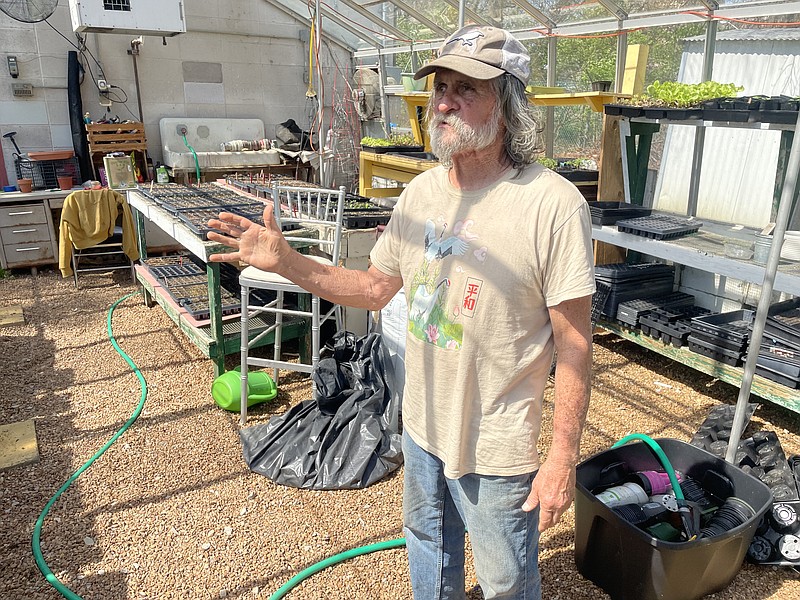

For about the past dozen years, Tippens has tried to be a force multiplier for urban community gardens here, focusing on underserved neighborhoods where people want to grow their own food. On any given day, you'll find him the at the old Chattanooga Food Bank greenhouse near Gateway Towers tending seedlings that will eventually be distributed to micro-gardens across the city.

"I'm not trying to save the world," Tippens said in an interview last week. "I'm just hoping that we can make this generation aware of some very simple things you can do locally that contribute to systemic change globally."

Tippens speaks the language of an activist. He talks about food inequity and the perceived evils of industrial farming.

Tippens' group, City Farms, has a board of directors and subsists on grants and the kindness of people who share its leader's vision. Tippen describes himself as "an old, white-haired hippie gardener" and a "fatally optimistic creative," and he admits that sometimes his dreams seem elusive.

"We are always scrambling," he said of the nonprofit's funding. "We are one step forward, one step to the side. We are always doing that dance."

Tippens is quick to point out that he can help people get an urban garden started, but it's up to the community to cultivate a core of volunteers willing to weed, fertilize and harvest the crops, such as tomatoes, squash, collard greens, onions and kale. A good example is a community of refugees from Africa and Central America who have come together to grow vegetables at a garden on Main Street. It's called the Neema Taking Roots Community Garden — "neema" in Swahili means "grace."

Tippens was doing urban gardening outreach in Daytona Beach, Florida, more than decade ago when he was asked to come to Chattanooga for a similar effort here. Over time, his work has been aligned with different churches, schools and nonprofit agencies.

He says some of the strongest bonds have been with schools (and by association, young people who see the need for changes in the way food is produced for the masses). Students at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and Chattanooga State Community College are among his most loyal volunteers, using City Farms Grower Coalition for service-learning opportunities.

(READ MORE: Food insecurity multiplied during COVID.)

On most days, students from UTC will be at the greenhouse at Gateway Towers replanting seedlings or fertilizing plants inside square plots bounded by landscaping timbers. City Farms has also helped establish gardens at local public schools such as Hardy Elementary, Orchard Knob Middle and The Howard School.

Tippens has high hopes for the garden at Howard, where members of an environmental sciences class are the gardeners. Hopes are that it can grow and be modeled after a program called Grow Dat, an urban farm and youth development organization in New Orleans that employs more than 100 people ages 16 to 22.

"I don't care that much about organic asparagus or different-colored carrots," Tippens said. "What I love is the relationships, especially with the young people. ... We need a new generation of people who will address the food-access inequity in our city."

Life Stories is published on Mondays. Contact Mark Kennedy at mkennedy@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6645.