Since March, at least 360 residents of the Chattanooga region have lost their lives due to the coronavirus, including 87 in Hamilton County and 59 in Whitfield County. August proved to be the deadliest month so far, with 122 lives lost across the region.

But often the details of those deaths remain a mystery.

People hospitalized with coronavirus are treated in a secure area, far from the public eye, and aren't allowed visitors. Even at the end of their lives, COVID-19 patients typically succumb to their illness without their loved ones by their side. Fear and stigma can cause those who survive to be reticent in talking about their experience. Family members of those who die rarely include COVID-19 as a cause of death in obituaries.

To mark six months since the first confirmed local infection, the Times Free Press sought community input from families and friends in order to remember and tell the important stories of at least a few who have died.

LEAVING A LEGACY

Andrew Marsh sat in his father's home office Monday afternoon surrounded by his family's ancestry.

On the walls were framed black and white photographs and paintings organized like a family tree.

"My dad had an affinity for history," Andrew said, sitting at his father's desk. "He was like the historian of our family. He made it his calling to learn and research as much as he could about our family's history. There are old pictures here in his office of people I don't even know."

The history of African Americans in the United States, Andrew said, only goes so far before it hits a dead end.

Hubert Marsh, Andrew's 69-year-old father - a native of LaFayette, Georgia, and local legend in Dalton - made it one of his life's missions to know where he came from. He understood the gravity of legacy. He knew the importance of what came before him and how that would influence what he left behind.

Hubert Marsh died Aug. 31 from complications with COVID-19. What he left behind was a lifetime of community service, a decorated career in public health, a growing family making a history of their own, a wife of 45 years and a son who feels he has enormous shoes to fill.

"Even with him gone, the shoes are getting bigger and bigger," Andrew said. "I don't know if I'll ever be able to grow into these things."

It's been a rough few years for the Marsh family.

Willisa Marsh, Hubert's daughter, died with health complications at the age of 36 in 2013. She was an elementary school teacher at Varnell and Valley Point schools in Dalton.

In the spring of 2019, Minnie Marsh, Hubert's wife, had two aneurysms and a stroke all at the same time and had to be rushed to the hospital. If Hubert hadn't been there, Minnie would have likely died.

Both Hubert and Minnie were retired at the time but they kept busy, especially Hubert. Hubert was the deacon and treasurer at Mount Zion Baptist Church in Dalton and worked for the Whitfield County Health Department for 30 years. He retired as director of the Teen Resource Health Center. Since then, Hubert had spent his free time volunteering at the hospital, kept busy at his church and served on several public boards including the Public Safety Commission in Dalton.

When Minnie had her stroke, she needed around-the-clock attention and Hubert became her primary caregiver.

Andrew, who lives in New Jersey with his family, made it a point to visit his parents once a month in Dalton. He came down in early March to celebrate Hubert's birthday on March 7. During that trip, the schools closed down in Whitfield County and everywhere else around the country.

"In the early '80s, my dad was the spokesperson for the North Georgia Health District and was on the front lines during the HIV/AIDS pandemic," Andrew said. "When we had our first death in the area, everyone panicked and people in the neighborhood wanted to burn down the house where this person lived. I'll never forget, my dad was on the 11 o'clock news talking about the case."

Hubert was tasked with calming the public. When 2020's pandemic showed up in Dalton, Hubert knew not to take the coronavirus lightly. Hubert and Minnie were both considered high-risk. Minnie survived breast cancer in 2015 and both had pre-existing respiratory illnesses.

Hubert put signs in the windows of their home saying visitors weren't welcome, made only emergency trips outside and had someone else pick up groceries. They kept things pretty tight, Andrew said, but one day earlier this summer someone came to the house who was asymptomatic who had recently been hospitalized for something other than COVID-19.

Minnie tested positive first while Hubert tested negative. The two did as best they could in terms of taking care of one another, but as Minnie started to recover, Hubert started showing symptoms of his own. By the time Hubert's results from a second COVID-19 test came back, he was already hospitalized at Emory in Atlanta.

Andrew drove 12 hours straight to Dalton from New Jersey around the same time Hubert drove himself to the hospital with a fever of 105. Hubert spent two days in the ICU and five weeks on a ventilator "before it was all too much," Andrew said.

Andrew said the outpouring of support from so many in the community has been overwhelming.

"He was a very proud member of this community," Andrew said. "I hated, hated, hated to see him go. He should have been here for some time. Then again, I can't think of anything else he could have done for me, our family and this community."

For the funeral services, the local police and fire departments celebrated Hubert in such a way that people asked Andrew if his father had led a second life as law enforcement. Officers stood guard and two ladder trucks hung an American flag over a four-lane road during the procession.

"He wanted nothing more than to add value to the community and to his church," Andrew said. "As as I sit here in his office and try to get his church business in order, I'm wondering how he did all of this and made it look so easy."

TURNED UPSIDE DOWN

It's been a month since Elizabeth Evans wheeled her parents into the hospital, and her "nightmare" of losing them both to COVID-19 began.

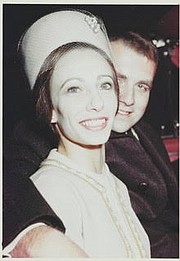

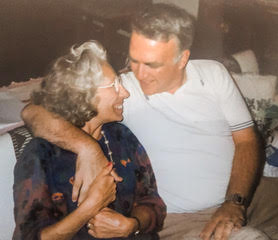

Evans said her mother and father - Carolyn and Jan Evans - met on a blind date, felt an instant connection and got married soon after.

Carolyn was born in Knoxville in 1939 and was known for her bright spirit and passion for helping others, especially children. She was creative and an accomplished musician who played flute with the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra, according to her obituary.

Jan, who was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1943 and grew up on Signal Mountain, was an engineer with an entrepreneurial mindset. He worked his way up through management at several companies and also taught at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

During their 54 years of marriage, the couple enjoyed many adventures together, Evans said. One of their favorites was when Jan took an assignment at the Ministry of Mines and Energy in Ethiopia and they moved to Africa for three years.

"They had a beautiful love story," she said.

Evans said her parents were older and both had their share of underlying health issues, but they were managing them well until the coronavirus came along.

"Prior to them testing positive for COVID, we had helped my dad get over a light flu, colds and other normal illnesses with no abnormal effects," she said.

The family did the best they could to social distance, although it went against their personalities and hospitable Southern upbringing. The parents, lonely and bored from time spent in isolation, would stop for food on the way home from their routine doctors' appointments.

Evans and her fiance, Tom Fitzpatrick, had her parents tested for the coronavirus as soon as they noticed the couple "struggling with some degree of respiratory distress," she said. Shortly after her mother's test results returned positive, Evans took her parents to CHI Memorial hospital.

Like many whose loved ones are admitted with COVID-19, Evans described the pain of not being able to visit them.

Her mother's condition deteriorated within days, and soon she was unable to communicate by phone.

Evans watched as she took her final breaths from the hallway through a window.

"I was not allowed in the room - could not touch her or be with her to comfort her. It was the most helpless feeling I have experienced," Evans said.

Still reeling from her mother's death, Evans turned her focus to her father, who continued to fight for his life.

"Just as that reality started to hit me I was forced to relive the struggle again with my father," she said.

After spending two weeks on the COVID unit, things were looking up for Jan. He was transferred to medical intensive care and in the process of rebuilding his strength when some new complications arose.

"It was 6 a.m., exactly three weeks from the day that we admitted them. The phone rang informing us that we needed to come to the hospital ASAP," Evans said.

Since he was no longer in the COVID unit, Evans and Fitzpatrick were able to be with Jan in his final moments.

"There is virtually no way to fully prepare for the loss of your parents under normal circumstances. To have something like COVID enter your life, and in less than a month take both your parents from you, has been life-changing," Evans said.

Fitzpatrick said they all knew the virus was real, but it wasn't until experiencing the "roller coaster" of COVID-19 that he could grasp the gravity of the situation.

"We were living our lives and doing the best we could, taking care of Elizabeth's parents and once this happened, this really changed everything for us," he said.

Evans said she doesn't blame the hospital and believes her parents received great care. She called one case manager in particular who was there for the entire process - her "lifeline."

"I can't give her enough thanks," Evans said, in addition to thanking the community for the outpouring of support she's received.

"I'm so overwhelmed with love and respect from people contacting me about them both, about what they did in this community," she said. "It should awaken people, because this took two amazing people in two weeks of each other."

'MAKE PEOPLE UNDERSTAND'

The historic Marsh House located on North Main Street in LaFayette was owned by Spencer Marsh, a slave owner and the great-great grandfather of Hubert Marsh. The Marshes built the house in 1836 using mostly slave labor. Spencer Marsh fathered a child with a Black slave. Wiley Marsh, Spencer Marsh's son, is the first recorded Black person in LaFayette.

The photos of Spencer, Wiley and many others are in Hubert's office. He worked as a volunteer tour guide at the historic location and always felt it was important to tell the truth about the past and to use the truth as lessons for the future.

When family and friends have reached out to Andrew since Hubert's passing, they often ask what they can do to help.

He tells them all the same thing.

"Wear a mask, socially distance yourself, get tested," he said. "There is so much misinformation about COVID-19. I'm here in a situation where I lost my father way earlier than he should have gone as a result of being around someone asymptomatic. I'm trying to make people understand it's not a big city problem."

Andrew doesn't want to see what happened to his family happen to anyone else's. "My dad is gone, but I have really made it my point and purpose to let people know we all have a responsibility to ourselves, our families and our fellow people who we come into contact with to look out for each other. This has nothing to do with politics. It has everything to do with decency and being what we've always considered ourselves of being, as Americans."

Evans said she's finding peace knowing that her parents are together, but she wants "anyone out there who is still claiming that COVID is fake" to know the truth.

"It is not," she said. "We need to think beyond ourselves and do what we can to protect the people that we love and come into contact with. Please take it seriously, and be safe."

Contact Patrick Filbin at pfilbin@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6476. Follow him on Twitter @PatrickFilbin.

Contact Elizabeth Fite at efite@timesfreepress.com or follow her on Twitter @ecfite.

Staff writer Wyatt Massey contributed to this story.