A little more than half a century since schools were integrated in Walker County, Georgia, most Black students in the county graduate without ever having a Black teacher.

While most see school integration as largely positive, the lack of Black role models in schools is seen as a negative aspect of the change that still lingers today.

"If Black children in some of our Walker County schools are such a minority that they never have an African American teacher, what can we do to help them have models, adults that are educated and professional that they can look up to?" said David Boyle, president of the Walker County Historical Society, which recently organized a panel discussion focused on the positive and negative effects of integration in Walker County. "It raises questions about things that could still be done to improve the lives of our Walker County citizens."

The African American schools in Walker County were started and run by African American educators, who were dispersed across all of the schools during integration, said Beverly Foster, president of the Walker County African American Historical and Alumni Association.

"It broke up some community camaraderie," Foster said of integration's effect on Black communities.

Rossville High School, now called Ridgeland High School, was integrated in 1967. Foster started attending the school in 1968, as part of the second integrated ninth grade class. She previously attended Wallaceville Elementary, a school for Black children in grades 1-8.

One shift she noticed with integration was in parental involvement. In Black schools, the PTA was controlled by African Americans.

"They ran the school, actually. It was a personal connection," Foster said.

Once schools were integrated, African American parents were scared to get involved, or did not feel comfortable getting involved, she said. They didn't know how to navigate this new system, and they no longer felt they had control over their children's lives at school.

Most of the African American parents' education stopped at high school, or at sixth grade, and they wanted more for their children, Foster said.

"But they did not know how to navigate with white parents who they felt were more educated than them and knew the ropes," she said. "So they lost that parental connection, to feel like they had a part in guiding their children."

Foster also felt the loss of Black teachers.

"Teachers in Black schools were a strong part of the community," she said.

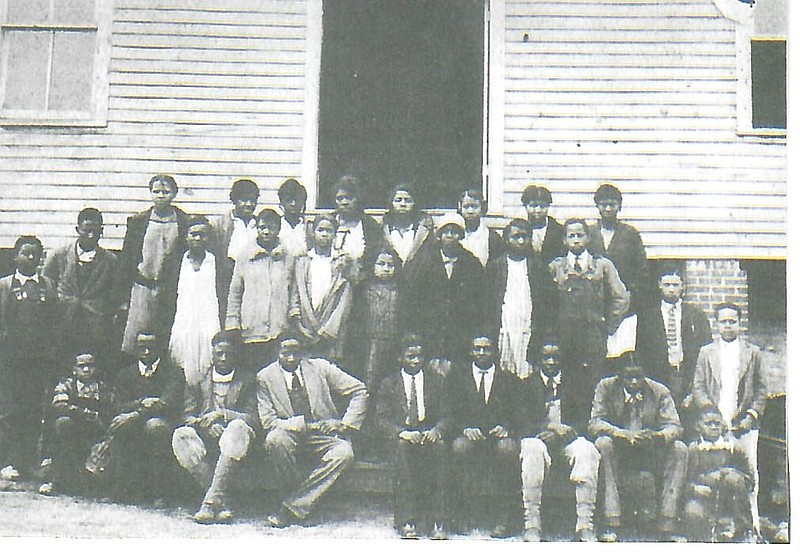

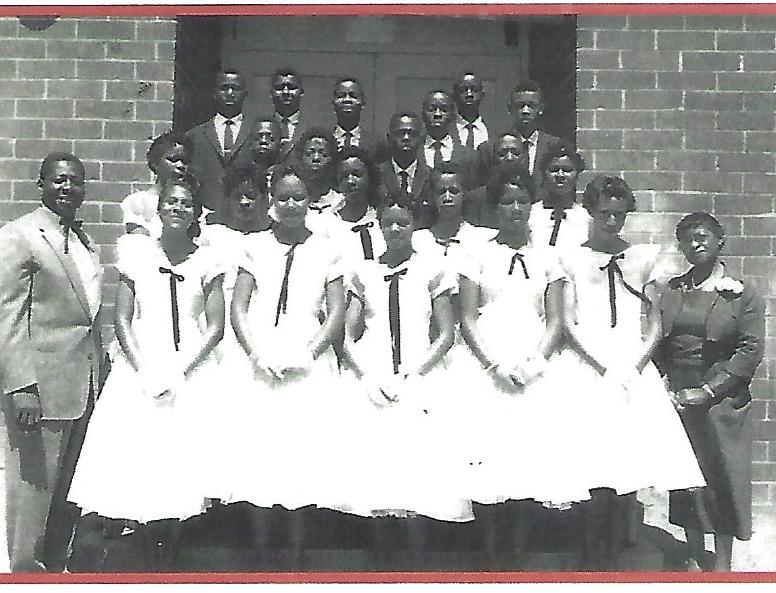

Contributed photo, courtesy of a donation to Walker County African American Historical and Alumni Association and Beverly C. Foster by Eunice Clements-Rooks and Marion Ward / The 1958 graduating class of Wallaceville Elementary School is shown outside the school's new brick facility. Rosa Belle Glenn-Clements, bottom right corner, was the modern brick "equalizing" school's first principal.

Contributed photo, courtesy of a donation to Walker County African American Historical and Alumni Association and Beverly C. Foster by Eunice Clements-Rooks and Marion Ward / The 1958 graduating class of Wallaceville Elementary School is shown outside the school's new brick facility. Rosa Belle Glenn-Clements, bottom right corner, was the modern brick "equalizing" school's first principal.She said the only Black teachers she saw at Rossville High were the two or three teachers from Rossville Junior High who came to the high school to pick up paperwork.

Foster, who became the first Black salutatorian at Rossville High, was in the more challenging classes and was usually the only Black student. It was a similar situation when she attended University of Georgia, where in classes of 300-400 people she was the only Black person in the room.

People might think that having to ride a crowded bus for hours to a school in another community would be a drawback to integration, and segregation generally required Black students to be bussed to schools outside their community.

Black students from Blowing Springs, an African American community just over the state line near St. Elmo, were forced to ride the bus all the way to LaFayette to attend Walker's only Black high school. Dade and Catoosa counties didn't have high schools for Black students. Instead, Catoosa paid for and transported its Black students to attend the Black high school in Whitfield County. Dade bussed Black high school students to Howard School in Chattanooga and paid for them to attend school out of state, Foster said.

Integration wasn't an entirely smooth process in Walker County. There was disruption in LaFayette when Hill High School, an African American school for grades 1-12, was integrated. The building burned under mysterious circumstances.

The process of integration went differently in rural areas like Walker and Chattooga counties than it did in urban areas, Foster said.

"Basically, now many of them have resegregated," she said of urban schools.

But in rural areas there is more of a historical connection between Black and white residents.

"In Walker County, we know who enslaved us," Foster said. "Some of us are even related."

Around 2,000 people were enslaved in Walker County, she said. That changed how the races interacted. It was easier to get a job with a family that enslaved your ancestors, because they knew your family, she said.

The African American population has dwindled from around 10% when Foster was growing up to around 5% now.

"Now that there's such a small population, there's very few women and men in positions of authority," she said. "We need to find a way to get more licensed African American teachers in the school system to have positive role models."

Diversity in leadership is helpful for all children, not just African American children, she added.

After graduating from college, Foster taught briefly in Hamilton County and saw a lack of Black educators there as well.

Foster said she thinks the schools need to recruit more teachers from historically Black colleges.

But overall, she feels integration was 90 percent positive for Black students in Walker County. There were more opportunities, a wider variety of classes you could take, she said of the advantages.

"I think we have a long way to go, but I think we are moving in the right direction," Foster said.