Since the Theato opened at 702 Market St. in 1906, Chattanoogans have had many theaters in which to watch movies. Depending on the year, 9 cents, 25 cents or slightly more could get you into a movie, perhaps two movies and a cartoon, newsreel and serial. You might even have a little extra for popcorn or candy.

By 1920, Chattanooga had 18 movie theaters, many on Market Street and Main Street. Chattanooga also had segregation, and Black movie fans did not have the freedom to enjoy the cinema as did their white counterparts. When able to attend, Blacks had to sit in the back of the theater or in the balcony. Should they want to sit anywhere in the theater, they had to visit one of those designated as "colored."

The 1940s had four thriving segregated theaters: the Amusu at 106 W. Main, the Liberty Theater at 312 E. 9th St., the Grand at 201 E. 9th St., and the Harlem or New Harlem at 220 W. 9th St. The Harlem opened in 1940, promising to be the leading "colored" theater in the entire South. Its policy, according to the News-Free Press on July 10, 1940, was "if it's a big production, the Harlem will bring it to you at popular prices."

The theater had the latest in air conditioning, comfort and "eye-soothing" projection equipment. The Liberty opened in July 1942, also promising to be the "South's finest theatre for colored people." The Amusu and the Grand had been around since the 1920s, the Grand being one of "Chattanooga's oldest motion picture houses." The Grand Amusement Company managed all four theaters, with Mose Lebovitz as president and Abe Solomon as vice-president. In 1958, the Grand suffered a terrible fire which killed the janitor, Joe Shelton, and led to the demise of the building. The Amusu building was vacant; the Harlem Theater building had been torn down. By 1960, the only segregated theater in the city directory was the Liberty, and by 1970, it, too, was gone.

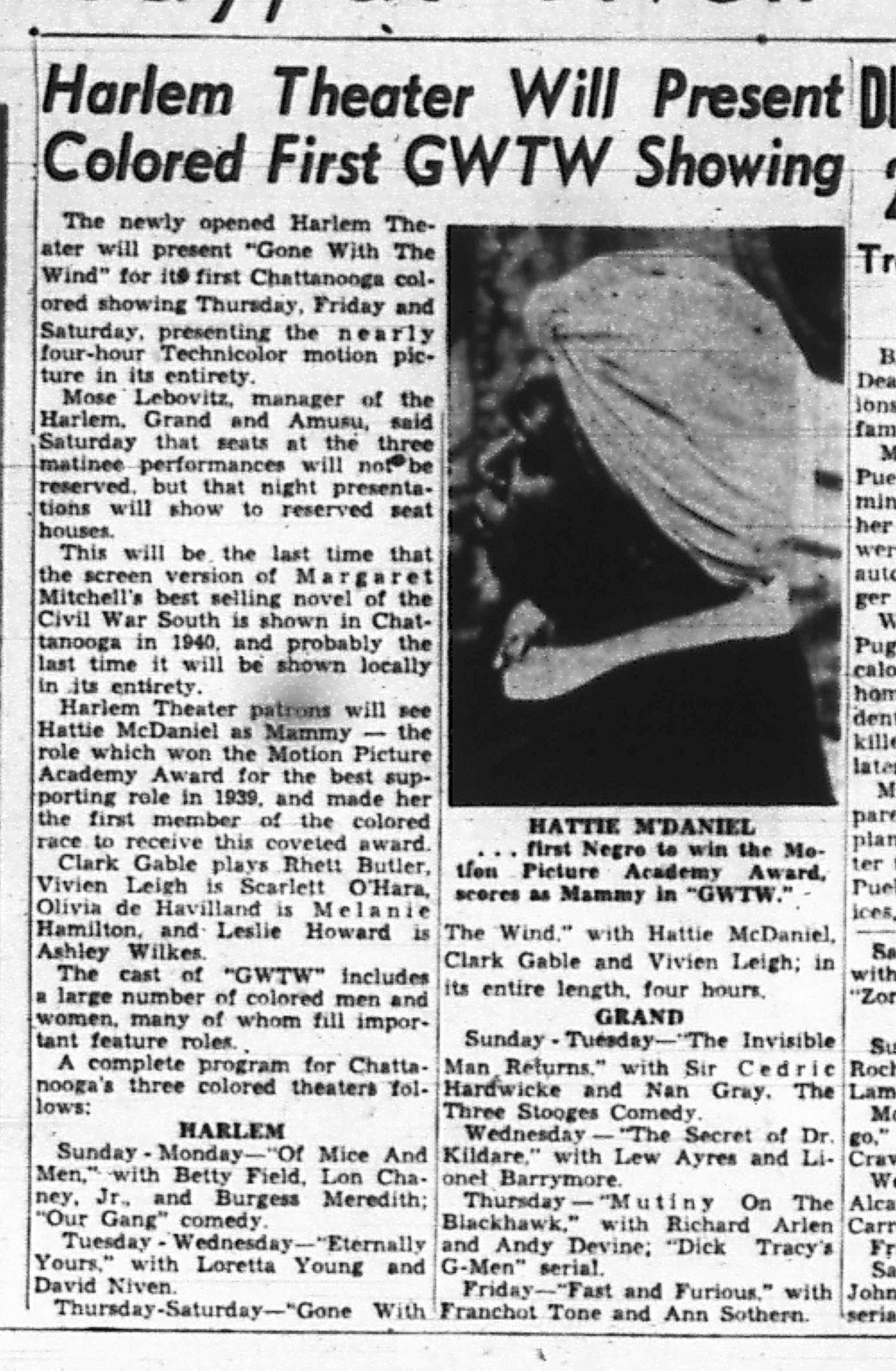

The segregated movie houses showed the same films as the others but with a few differences. Blockbuster movies often came to the "colored" theaters after their first showing. Movie advertisements in the newspaper were different. The local newspapers carried no theater ads for the Harlem, Liberty, Amusu or Grand. The News-Free Press printed the movie schedule for "colored" theaters but not any ads like those for the Tivoli or Rialto. When "Gone with the Wind" came to the Harlem in July 1940, the News-Free Press printed an article on the movie's first run at a "colored" theater. Instead of featuring Clark Gable or Vivian Leigh, the newspaper story highlighted Hattie McDaniel and the large number of "colored" men and women in the cast who filled many important roles.

Along with Hollywood spectaculars, movie watchers at Chattanooga's segregated theaters could also see a "race film." These were films for Black audiences that featured an all-Black cast, produced by independent Black film studios. Producers made and circulated these films between 1915 and the early 1950s. A 1941 film, "The Blood of Jesus," played at the Grand, Harlem and Amusu from 1942 to 1950, and was popular in Black churches. In 1991, it was the first race film to be placed on the National Film Registry. Many of the race films showcased musical talents such as Count Bassie, Cab Calloway, Ethel Waters and Lena Horne. Others starred comedians such as Lincoln Perry, aka Stepin Fetchit, considered to be the first Black actor to have a successful film career. Race films offered an outlet for Black talent in the early film industry.

One race film that showed not only at the segregated theaters but also at the Tivoli was "Stormy Weather." The film was based on the life of its leading man, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, and starred Lena Horne, Cab Calloway and Fats Waller in more than 20 musical numbers. Though not without some stereotypical elements and racial caricatures, the film surpassed others in offering Black talent a performance showcase. Its run at the Tivoli began Jan. 27, 1944.

The Harlem, Grand, Liberty and Amusu provided a place for Black audiences to see movies of all genres and to see Black performers in roles not given them during segregation. Chattanooga's "colored" theaters have gone due to economic changes, population movement and integration, but for those who attended them, they delivered the magic of the movies.

Contact Suzette Raney, archivist at the Chattanooga Public Library, at localhistory@lib.chattanooga.gov or call 423-643-7725.