Read more Chattanooga History Columns

- Gaston: Paul John Kruesi was Edison's right-hand man

- Robbins: The old Richardson's house and the Civil War

- Gaston: James Williams was a man of the world

- Raney: Mason Evans, the 'Wild Man of the Chilhowee'

- Gaston: The legacy of Adolph Ochs endures

- Martin: Ed Johnson said, 'I have a changed heart,' the day before his lynching in Chattanooga on 1906

- Thomas: The inventiveness of Judge Michael M. Allison

- Moore: Chattanooga's first Chinese community

- Summers, Robbins: Chattanooga's Tuskegee Airman - Joseph C. White

- McCallie: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says so!

- Gaston: John McCline's Civil War - from slave to D.C. parade

- Raney: Exploring Chattanooga businesses in the Green Book

- Elliott: Remembering the Freedmen's Bureau in Chattanooga

- Gaston: Nancy Ward was a beloved, respected Tennessean

- Martin: Prohibition - the noble experiment

- Elliott: 'A shameful, disgraceful deed': The destruction of the Sewanee cornerstone

- Gaston: Robert Cravens was ironmaster, Chattanooga area's first commuter

- Robbins: Dr. T.H. McCallie's Christmas 1863

- Robbins: Journalist writes of a trip to Missionary Ridge in 1896

- Summers, Robbins: Mine 21 disaster - gone but not forgotten

- Elliott: Collegedale incorporates to avoid Sunday 'blue laws'

- Gaston: 'Marse Henry' Watterson's journalism fame began in Chattanooga

- Robbins: Orchard Knob battle recalled in 1895

- Elliott: Chattanoogans joined in an 'orgy of joy and gladness' on Armistice Day, 1918

- Thomas: Noted service, speakers are marks of Rotary Club of Chattanooga since 1914

- Summers and Robbins: Remembering noted Tennessee author North Callahan

- Raney: 'I auto cry, I auto laugh, I auto sign my autograph'

- Gaston: Sequoyah's alphabet enriched Cherokees

- Robbins: A look at Sam Divine's life during the Civil War

- Robbins: Memories of a Confederate nurse

- Robbins: More notes from Bradford Torrey's 1895 visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Robbins: Journalist in 1895 details visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Elliott: Telephone exchange firebombing was distraction for grocery store robbery

- Gaston: Worcester brought Christ's message to Cherokee at Brainerd Mission

- Robbins: 1896 travel diary: 'A Week on Walden's Ridge'

- Gaston: Elizabeth Strayhorn, WAC Commandant at Fort Oglethorpe

- Robbins: The history of the Friends of Moccasin Bend National Park

- Moore: Do you own a Sears Roebuck home?

- Summers and Robbins: Camp Nathan Bedford Forrest in World War II

- Gaston: Hiram Sanborn Chamberlain remembered

- Elliott: Daisy the center of tile, ceramic manufacturing in Hamilton County

- Gaston: FDR inaugurates the Chickamauga Dam

- Summers, Robbins: Interned WWII Germans had it easy at Camp Crossville

- Elliott: A war correspondent on Lookout Mountain

- Gaston: Chickamaugas finally bury hatchet in Tennessee Valley

- Gaston: Chickamaugas in Chattanooga

- Robbins: The history of the Riverbend festival

- Raney: Sadie Watson, the first woman elected in Hamilton County government

- Moore: Remembering Chattanooga's Hawkinsville community

- Elliott: Welsh coal miners transformed Soddy after the Civil War

- Gaston: Chattanooga's best-kept secret

- Elliott: Cabell Breckinridge loses his horse

- Raney: Martin Fleming is the people's judge

- Gaston: The amazing career of Francis Lynde

- Martin: Hamilton County's Name Sake: Alexander Hamilton

- Summers, Robbins: The crosses at Sewanee

- Bledsoe: The fiery truce at Kennesaw Mountain

- Moore: Talented architect's life cut short by tragedy

- Rydell: Chattanooga's place in soccer history

- Robbins: Tennessee Coal, member of the First Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Raney: In the barber chair

- Lanier: Becoming the Boyce Station Neighborhood Association

- McCallie: John P. Franklin: Living history among us

- Barr: Chattanooga's first railroad: The Underground Railroad

- Summers, Robbins: Charles Bartlett was a Pulitzer Prize winner, Kennedy confidant

- Rainey: 'We have seen it'

- Elliott: Feinting and fighting at Running Water Creek and Johnson's Crook

- Gaston: The Spring Frog Cabin at Audubon Acres

- Raney: Wauhatchie Pike was moonshine motorway

- Robbins: Oakmont was home of venerable Williams clan

- Summers and Robbins: Rebirth of the Mountain Goat Line

- Elliott: Bad investments led to Soddy Bank failure in 1930

- Summers and Robbins: Pearl Harbor attack left football behind

- Gaston: Jolly’s Island namesake had long ties with Sam Houston

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Indian Agent

- Moore: Did you know about St. Elmo's other two cemeteries?

- Summers: Orme - Marion County's almost lost community

- Davis: Spooky revival at Sharp Mountain in 1873

- Robbins: The story of Longholm

- Raney: Women labored to help the U.S. win World War I

- Even in the city, the 'wheel' changed everything

- Murray: Confederate dilemma after Chickamauga

- J.B. Collins — Newsman extraordinaire

- Robbins: The Story of the Lyndhurst Mansion

- Chattanooga artist and wife lost on the Lusitania

- Chattanooga History Column: Battelle, Alabama and the Battelle Institute

- John Ross, a founder of Chattanooga

- Hamilton County casualties in World War I

- Chattanooga Power Couple

- 'Somewhere in France'

- The Ray Moss family

- Battery B from Chattanooga

- Ulysses S. Grant, Clark B. Lagow, and the Chattanooga Bender

- Songbirds Museum Timeline

- Hamilton County World War 1 roster

- The Soddy Girl and the Memphis Belle

- Blues icon Bessie Smith was the Empress of Soul

- Women's Army Corps at Chickamauga

- Emma Bell Miles' life at the top of the 'W'

- The Tivoli Wurlitzer is one of Chattanooga's priceless assets

- Chattanooga in struggle for freedom during Civil War

- October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic

- Eli Lilly and the Ditch of Death

- One hundred years ago, Chattanooga goes to war

- The legacy of Anna Safley Houston

- Harriet Whiteside was ahead of her time

- Southern Adventist University

- Chattanooga native's writings aided Civil Rights movement

- Zion College, Chattanooga's only African American College

- The North Shore's hidden past

- Mayme Martin -- Businesswoman and community leader

- Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom

- Top of Cameron Hill was price of rerouting interstate

- Cameron Hill has rich history

- Temperance movement included Harriman university

- The sweetest music this side of Heaven

- Conquistadors at Chattanooga

- Chattanooga and the 'General'

- Chattanooga's first Thanksgiving, 1863

- Chattanooga's greatest flood caught city unaware

- Opening the Cracker Line

- European trip in 1900 enlightens Sophia Scholze Long

- Sophia Scholze Long spoke out when others were silent

- Little South Pittsburg and its big silent movie stars

- Lot attendant recalls hottest job in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's Forest Hills is final resting place for known, unknown

- Burritt College -- Pioneer of the Cumberlands

- Chattanooga's nicknames trace city's evolution

- The 25th annual meeting of the Tennessee Press Association

- Clemons Brothers Furniture Store

- The Short Life of the USS Chattanooga

- Ellen Jarnagin McCallie lived a truly remarkable life

- Dr. Jonathan Bachman was a revered city father

- Second guessing the Confederate failure on Missionary Ridge

- Nancy Kefauver, ambassador for the arts

- William Gibbs McAdoo kept his Southern roots

- Chattanooga's Secretary of the Treasury

- Howard Baker remembered as a statesman/photographer who snapped history

- Tivoli's last picture show

- The history of one of Chattanooga's oldest businesses

- Chattanooga's roller derby skaters

- Myths of Coca-Cola in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's neighborhood grocery stores

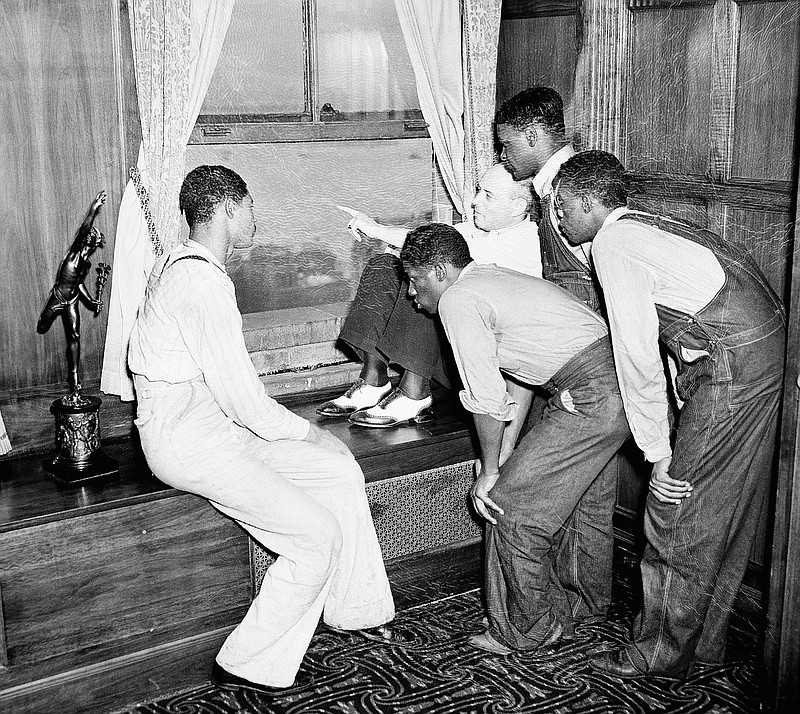

- The tale of the Scottsboro Boys

- The people's history of Chattanooga

- Howard School is Chattanooga's reminder of Reconstruction

- Elevator operator, painter, mystery man: meet Rice Carothers

- Raulston Schoolfield made enemies amid his rise to power

- Website lets users peer into Chattanooga's past

- The flood of 1917

- Chattanooga's 'wickedest woman' buried at Forest Hills

- History of Cummings Highway

Much has been written about the Scottsboro Boys, nine black teenagers accused of raping two white women in 1931. The landmark set of legal cases included a frameup, an all-white jury, rushed trials, an attempted lynching and an angry mob - which led to international outrage and legal reforms.

It is well documented that on March 25, 1931, nine Negro young men were charged with the rape of two white women, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates. All were hoboing on a Southern Railway freight train from Chattanooga bound for Memphis. The alleged crime occurred in Paint Rock in Jackson County, Ala. Scottsboro, the county seat, became the site of the first of the famous trials.

The Chattanooga legal community became involved in the case early on through the services of attorneys Stephen Roddy and George W. Chamblee, who represented the defendants.

Stephen Roddy was born in Centralia, Mo., in 1890, and attended the Chattanooga College of Law. He joined the law firm headed by Alexander W. Chambliss, who later became a justice on the Tennessee Supreme Court. After serving in World War I, Roddy became prominent in Democratic politics at both the local and state levels. He was a candidate for attorney general of Hamilton County in 1926, running against the incumbent J.J. Lively (who won) and George W. Chamblee in a three-man race for the Democratic nomination.

When the Scottsboro trial was put on the docket just two weeks after the alleged crime in April 1931, a group of black ministers in Chattanooga's Interdenominational Ministers Alliance promised Roddy $120 to represent the Scottsboro accused.

No local attorneys spoke up for the defendants when Judge Alfred Hawkins called the cases, so Roddy stepped forward. The Chattanooga attorney attempted to avoid the appointment by claiming he did not want to try the case alone. The judge kept Roddy on the case by adding Milo Moody, a 69-year-old Scottsboro attorney who had not defended a case in decades, to represent the young black men.

Under trying conditions, Roddy and Moody gave a perfunctory defense on behalf of seven of the defendants. All but one of the nine defendants were eventually convicted of rape and sentenced to death.

Two organizations, the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Communist propaganda group, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people (NAACP), competed to represent the defendants. Roddy had declined to stay on the case when informed that the fees would be raised by holding mass meetings among Negroes. Clarence Darrow of Scopes Trial fame declined to become involved due to dissension between the two groups.

The ILD employed Chattanooga attorney George W. Chamblee to join the defense of the case led by Samuel Leibowitz, a respected New York criminal defense attorney. Chattanooga attorney Raulston Schoolfield was allegedly asked to join the defense team but disagreed with Leibowitz's trial strategy of attacking the community and the two white girls. He refused to become involved.

Chamblee, the grandson of a decorated Confederate veteran and member of a prominent Tennessee family, had no trouble with unpopular defendants and causes including Communists and radicals. He represented many moonshiners during the Prohibition era and claimed he had tried more than 800 murder cases with none of his clients being electrocuted or hanged. A graduate of Mercer Law School, he served as Chattanooga city attorney and district attorney general in Hamilton County before becoming involved in Scottsboro.

Another Chattanoogan, gynecologist Edward Reisman Sr., testified for the defense that the physical facts of the medical examination failed to support the allegations of one of the women of being sexually assaulted by the defendants. In spite of Dr. Reisman's testimony and the inconclusive testimony of the initial examining physician, Dr. R.R. Bridges, the defendants were convicted. Judge James E. Horton courageously granted the defendants a new trial, which led to his defeat in the next election.

On Nov. 21, 2013, the Alabama Parole Board pardoned all defendants living and dead and instructed that their convictions be stricken from court records. Three Chattanoogans, Roddy, Chamblee and Reisman, took unpopular stands and played a role in the tragic Scottsboro trials, which help establish new constitutional standards involving competency of counsel and exclusion of blacks from jury service.

Two outstanding books on the trials stand out: Dan Carter's "Scottsboro," Louisiana Press (1986) and James Goodman's "Stories of Scottsboro," Vintage Books (1994).

Jerry Summers is an attorney with Summers, Rufolo and Rogers. Mickey Robbins, an investment adviser with Patten and Patten, contributed to this article. For more, visit chattahistoricalassoc.org.