Nov. 26, 2018, marked the 50th anniversary of the vote to incorporate the Collegedale community as a Tennessee municipality. Collegedale's unique flavor as a majority Seventh-day Adventist community had much to do with the incorporation, and more particularly, the almost now-vanished enactment of Sunday "blue laws," which required that businesses close to observe the day. Adventists observe the Sabbath on Saturday, and frequently conduct the personal business adherents of other religions do on Saturday on Sunday. The center of the community, then known as Southern Missionary College, came to that part of Hamilton County in 1916 after Sunday laws were invoked against Adventists in Graysville, Tennessee, in 1895.

In 1968, Chattanooga enforced Sunday laws. Enforcement of blue laws in Collegedale would have caused serious disruption of the community's economy. Stores there did a large business on Sunday, and since businesses elsewhere were closed, many non-Adventists came to town to shop. Further, residents and students of the college, who were not working on Saturday for religious reasons, also would not work on Sunday.

Faced with increasing poverty in the inner city, and the reputation of being one of America's most polluted cities, a population shift to Chattanooga's suburbs (which affected the city's tax base) was well underway. A change in Tennessee's annexation laws made it possible for Chattanooga and other municipalities to annex territory by ordinance, without input from the residents of an affected area. Whether real or imagined, Collegedale residents perceived a threat of being annexed by Chattanooga, which would include its Sunday closing laws.

According to Glenn McColpin, the attorney who filed the petition to incorporate on behalf of its advocates, the residents of the Collegedale community had discussed incorporation as early as 1963. The effort in 1968 began when the residents of neighboring Ooltewah held a town hall meeting to discuss incorporation of that community. Chattanooga Mayor Ralph Kelley made it clear that efforts to incorporate on the periphery of Chattanooga would bring about annexation from the larger city. Indeed, the law at that time allowed a larger city (of more than 100,000 citizens) to delay incorporation of an area within five miles of its boundaries for a period of 15 months. Chattanooga annexed a portion of I-75 (then permissible, but later an illegal "corridor" annexation) to put it within five miles of Ooltewah and Collegedale, buying itself a bit of time. The group favoring incorporation in Ooltewah dropped its plans.

Read more Chattanooga History Columns

- Gaston: Paul John Kruesi was Edison's right-hand man

- Robbins: The old Richardson's house and the Civil War

- Gaston: James Williams was a man of the world

- Raney: Mason Evans, the 'Wild Man of the Chilhowee'

- Gaston: The legacy of Adolph Ochs endures

- Martin: Ed Johnson said, 'I have a changed heart,' the day before his lynching in Chattanooga on 1906

- Thomas: The inventiveness of Judge Michael M. Allison

- Moore: Chattanooga's first Chinese community

- Summers, Robbins: Chattanooga's Tuskegee Airman - Joseph C. White

- McCallie: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says so!

- Gaston: John McCline's Civil War - from slave to D.C. parade

- Raney: Exploring Chattanooga businesses in the Green Book

- Elliott: Remembering the Freedmen's Bureau in Chattanooga

- Gaston: Nancy Ward was a beloved, respected Tennessean

- Martin: Prohibition - the noble experiment

- Elliott: 'A shameful, disgraceful deed': The destruction of the Sewanee cornerstone

- Gaston: Robert Cravens was ironmaster, Chattanooga area's first commuter

- Robbins: Dr. T.H. McCallie's Christmas 1863

- Robbins: Journalist writes of a trip to Missionary Ridge in 1896

- Summers, Robbins: Mine 21 disaster - gone but not forgotten

- Elliott: Collegedale incorporates to avoid Sunday 'blue laws'

- Gaston: 'Marse Henry' Watterson's journalism fame began in Chattanooga

- Robbins: Orchard Knob battle recalled in 1895

- Elliott: Chattanoogans joined in an 'orgy of joy and gladness' on Armistice Day, 1918

- Thomas: Noted service, speakers are marks of Rotary Club of Chattanooga since 1914

- Summers and Robbins: Remembering noted Tennessee author North Callahan

- Raney: 'I auto cry, I auto laugh, I auto sign my autograph'

- Gaston: Sequoyah's alphabet enriched Cherokees

- Robbins: A look at Sam Divine's life during the Civil War

- Robbins: Memories of a Confederate nurse

- Robbins: More notes from Bradford Torrey's 1895 visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Robbins: Journalist in 1895 details visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Elliott: Telephone exchange firebombing was distraction for grocery store robbery

- Gaston: Worcester brought Christ's message to Cherokee at Brainerd Mission

- Robbins: 1896 travel diary: 'A Week on Walden's Ridge'

- Gaston: Elizabeth Strayhorn, WAC Commandant at Fort Oglethorpe

- Robbins: The history of the Friends of Moccasin Bend National Park

- Moore: Do you own a Sears Roebuck home?

- Summers and Robbins: Camp Nathan Bedford Forrest in World War II

- Gaston: Hiram Sanborn Chamberlain remembered

- Elliott: Daisy the center of tile, ceramic manufacturing in Hamilton County

- Gaston: FDR inaugurates the Chickamauga Dam

- Summers, Robbins: Interned WWII Germans had it easy at Camp Crossville

- Elliott: A war correspondent on Lookout Mountain

- Gaston: Chickamaugas finally bury hatchet in Tennessee Valley

- Gaston: Chickamaugas in Chattanooga

- Robbins: The history of the Riverbend festival

- Raney: Sadie Watson, the first woman elected in Hamilton County government

- Moore: Remembering Chattanooga's Hawkinsville community

- Elliott: Welsh coal miners transformed Soddy after the Civil War

- Gaston: Chattanooga's best-kept secret

- Elliott: Cabell Breckinridge loses his horse

- Raney: Martin Fleming is the people's judge

- Gaston: The amazing career of Francis Lynde

- Martin: Hamilton County's Name Sake: Alexander Hamilton

- Summers, Robbins: The crosses at Sewanee

- Bledsoe: The fiery truce at Kennesaw Mountain

- Moore: Talented architect's life cut short by tragedy

- Rydell: Chattanooga's place in soccer history

- Robbins: Tennessee Coal, member of the First Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Raney: In the barber chair

- Lanier: Becoming the Boyce Station Neighborhood Association

- McCallie: John P. Franklin: Living history among us

- Barr: Chattanooga's first railroad: The Underground Railroad

- Summers, Robbins: Charles Bartlett was a Pulitzer Prize winner, Kennedy confidant

- Rainey: 'We have seen it'

- Elliott: Feinting and fighting at Running Water Creek and Johnson's Crook

- Gaston: The Spring Frog Cabin at Audubon Acres

- Raney: Wauhatchie Pike was moonshine motorway

- Robbins: Oakmont was home of venerable Williams clan

- Summers and Robbins: Rebirth of the Mountain Goat Line

- Elliott: Bad investments led to Soddy Bank failure in 1930

- Summers and Robbins: Pearl Harbor attack left football behind

- Gaston: Jolly’s Island namesake had long ties with Sam Houston

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Indian Agent

- Moore: Did you know about St. Elmo's other two cemeteries?

- Summers: Orme - Marion County's almost lost community

- Davis: Spooky revival at Sharp Mountain in 1873

- Robbins: The story of Longholm

- Raney: Women labored to help the U.S. win World War I

- Even in the city, the 'wheel' changed everything

- Murray: Confederate dilemma after Chickamauga

- J.B. Collins — Newsman extraordinaire

- Robbins: The Story of the Lyndhurst Mansion

- Chattanooga artist and wife lost on the Lusitania

- Chattanooga History Column: Battelle, Alabama and the Battelle Institute

- John Ross, a founder of Chattanooga

- Hamilton County casualties in World War I

- Chattanooga Power Couple

- 'Somewhere in France'

- The Ray Moss family

- Battery B from Chattanooga

- Ulysses S. Grant, Clark B. Lagow, and the Chattanooga Bender

- Songbirds Museum Timeline

- Hamilton County World War 1 roster

- The Soddy Girl and the Memphis Belle

- Blues icon Bessie Smith was the Empress of Soul

- Women's Army Corps at Chickamauga

- Emma Bell Miles' life at the top of the 'W'

- The Tivoli Wurlitzer is one of Chattanooga's priceless assets

- Chattanooga in struggle for freedom during Civil War

- October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic

- Eli Lilly and the Ditch of Death

- One hundred years ago, Chattanooga goes to war

- The legacy of Anna Safley Houston

- Harriet Whiteside was ahead of her time

- Southern Adventist University

- Chattanooga native's writings aided Civil Rights movement

- Zion College, Chattanooga's only African American College

- The North Shore's hidden past

- Mayme Martin -- Businesswoman and community leader

- Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom

- Top of Cameron Hill was price of rerouting interstate

- Cameron Hill has rich history

- Temperance movement included Harriman university

- The sweetest music this side of Heaven

- Conquistadors at Chattanooga

- Chattanooga and the 'General'

- Chattanooga's first Thanksgiving, 1863

- Chattanooga's greatest flood caught city unaware

- Opening the Cracker Line

- European trip in 1900 enlightens Sophia Scholze Long

- Sophia Scholze Long spoke out when others were silent

- Little South Pittsburg and its big silent movie stars

- Lot attendant recalls hottest job in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's Forest Hills is final resting place for known, unknown

- Burritt College -- Pioneer of the Cumberlands

- Chattanooga's nicknames trace city's evolution

- The 25th annual meeting of the Tennessee Press Association

- Clemons Brothers Furniture Store

- The Short Life of the USS Chattanooga

- Ellen Jarnagin McCallie lived a truly remarkable life

- Dr. Jonathan Bachman was a revered city father

- Second guessing the Confederate failure on Missionary Ridge

- Nancy Kefauver, ambassador for the arts

- William Gibbs McAdoo kept his Southern roots

- Chattanooga's Secretary of the Treasury

- Howard Baker remembered as a statesman/photographer who snapped history

- Tivoli's last picture show

- The history of one of Chattanooga's oldest businesses

- Chattanooga's roller derby skaters

- Myths of Coca-Cola in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's neighborhood grocery stores

- The tale of the Scottsboro Boys

- The people's history of Chattanooga

- Howard School is Chattanooga's reminder of Reconstruction

- Elevator operator, painter, mystery man: meet Rice Carothers

- Raulston Schoolfield made enemies amid his rise to power

- Website lets users peer into Chattanooga's past

- The flood of 1917

- Chattanooga's 'wickedest woman' buried at Forest Hills

- History of Cummings Highway

But McColpin and Collegedale residents favoring incorporation figured Chattanooga did not in fact want to annex their community, which was somewhat isolated in a pocket hemmed in by the ridges and mountains of East Hamilton County. Further, as the law required annexations to be contiguous, Chattanooga would have to bring in a large tract between its then city limits and Collegedale, and provide municipal services - police and fire protection, garbage services, street lighting, road paving, etc. Chattanooga simply was not in a position to do that in 1968.

The vote was held on Tuesday, Nov. 26, 1968. Of the estimated 400 registered voters, 290 cast ballots. The vote was 216 for, 74 against. Many of the area's total of 3,000 residents were college students and not qualified to vote. The initial area of the city was 2,900 acres.

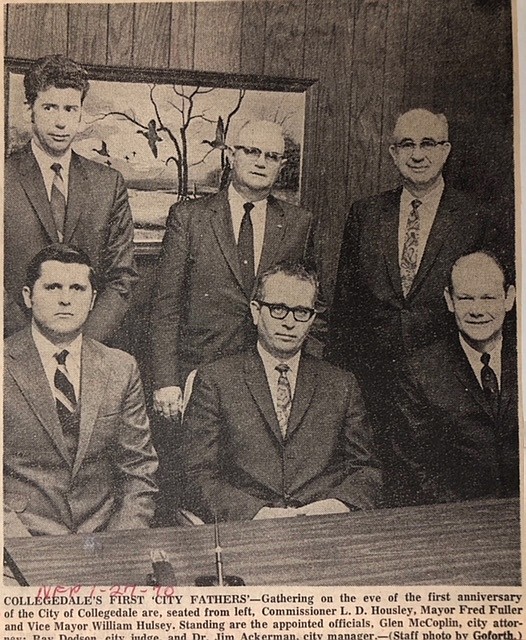

In the following weeks, McColpin, the new city's attorney, and others struggled with the legal and practical issues of establishing the city government. An election was held for the town's first city commission on Jan. 28, 1969, and Fred Fuller, L.D. Housley and William Hulsey were elected the first commissioners. Fuller and Hulsey were Adventists, Housley was not. Fuller, who had the largest vote total, was selected by his two fellow commissioners as the town's first mayor, and Hulsey was elected vice mayor. Interestingly, both Fuller and Hulsey, who are now deceased, would return to serve on the city commission decades later. By Jan. 1, 1970, the town was fully functioning and offering all necessary services to its citizens.

In the end, Chattanooga did not exercise its right to interfere with the incorporation. In 1970, Fuller was quoted as saying that "[a]ctually, Chattanooga officials have been very helpful to us. We've gone to them for advice, and they couldn't have been more cooperative." And as time has passed and the two municipalities know about one other, mutually beneficial cooperation between the two has continued.

Local attorney and historian Sam D. Elliott has been Collegedale's city attorney since 1999. For more information, visit Chattahistoricalassoc.org.