The New York Times' COVID-19 mapping and coverage had a new twist for us Friday: On the paper's "hot spots" map, Tennessee lit up like a hot red bullseye.

The top of the national story began reassuringly: "Known daily cases continue to fall and are now below 100,000 per day nationally, 19 percent lower than two weeks ago. Cases are declining in almost every state."

But that's not so for Tennessee.

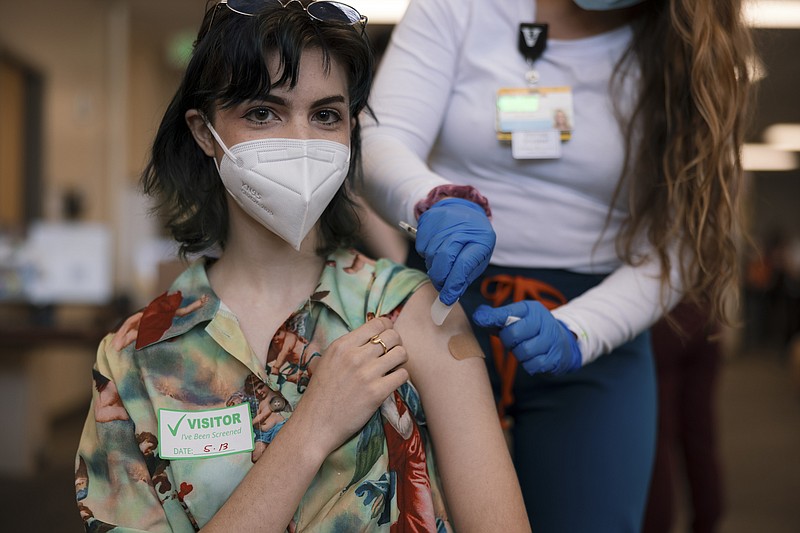

In our state, where vaccines and masks have largely been discouraged by our state government officials, we're seeing a 65% spike with 4,051 daily average cases.

Or, put another way, Tennessee is still seeing 59 new daily cases per 100,000 population. That compares to the nation's 28 new daily cases per 100,000, according to the Times COVID tracker

We're No. 1. Again.

Except in vaccinations, where our paltry 55% vaccination rate puts us in bottom seven states and territories.

This comes at a time when the BA.5 subvariant, the most transmissible variant of the virus yet, threatens a fresh wave across the nation even among those who have recovered from COVID fairly recently.

There is good news.

COVID-19 vaccines tweaked to better match today's omicron threat are expected to roll out in a few weeks. A story on Friday's Chattanooga Times Free Press front page tells about it and discusses who should get one -- and how soon.

But then it seems it isn't just COVID-19 vaccines that bring big yawns from disease prevention-averse people in our region.

Politico wrote in April that public health experts, pediatricians, school nurses, immunization advocates and state officials in 10 states told reporters they are worried that an increasing number of families are projecting their hesitancy attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine onto shots for measles, chickenpox, meningitis and other diseases -- even polio.

Kindergarten vaccination rates in Tennessee, a state once heralded for its childhood vaccination program, dipped to a record low of 93.7% in the past year, according to story in this paper last week.

Worse still, Hamilton County kindergarteners fall among the least vaccinated in the state, according to a Tennessee Department of Health annual report.

The percentage of public school students in Hamilton County who were fully immunized against these commonly preventable and still dangerous childhood diseases is only 89.7%. Only five other counties have rates worse than ours.

Vaccination rates are supposed to remain above 95%. But since the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Tennessee counties that meet that fully immunized threshold decreased from 72 to 43 counties, representing a 40.3% decrease, according to the state report. That means only 45% of Tennessee's 95 counties are at the 95% minimum threshold.

This is beyond dangerous for our children and ourselves.

"With the re-emergence of polio in New York and other developed nations, it's more prudent now more than ever to obtain these vaccines," Dr. Stephen Miller, health officer for the Hamilton County Health Department, said.

Politico found that Tennessee physicians reported 14% fewer vaccine doses were given to children under 2 in 2020 and 2021 than before the pandemic.

But it isn't just a problem in Tennessee.

In Florida, 2-year-old routine rates for all immunizations in county-run facilities plummeted from 92.1% in 2019 to 79.3% in 2021.

In Georgia, Hugo Scornik, a pediatrician and president of the Georgia Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, told Politico he was alarmed by the introduction of several bills in the state legislature last year to limit vaccinations, including one that would have ended immunization requirements in schools. Several states considered similar pieces of legislation that would have either removed or whittled away at school vaccination requirements, though none moved forward, he said.

"We just want to keep measles, polio, and all the things we vaccinate against out of the political arena," Scornik said.

We're afraid those horses are long out the barn door. Along with ticking up illness rates.

Nationally, outbreaks of diseases such as measles, which at one time was eliminated in the United States but has since resurfaced, are becoming increasingly common as vaccinations wane.

The U.S. reported more than 1,200 measles cases in 2019 -- the greatest number since 1992 and since the virus was declared eliminated in 2000 -- according to the CDC.

And then there's polio.

In July, a young, unvaccinated adult in New York became paralyzed with polio, and a new CDC report shows the virus may have been circulating there undetected since April.

It was the first report of polio in the U.S. since 2013.

We must do better than this. We must be better than this.