Photo Gallery

Haunted House

The annual EMOBA Haunted House is busy scaring people for 2 weeks out of the year...

The FBI is not calling Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez a terrorist - not yet, at least.

Officials, for now, are labeling him something else. The words used at a news conference Wednesday were more nuanced.

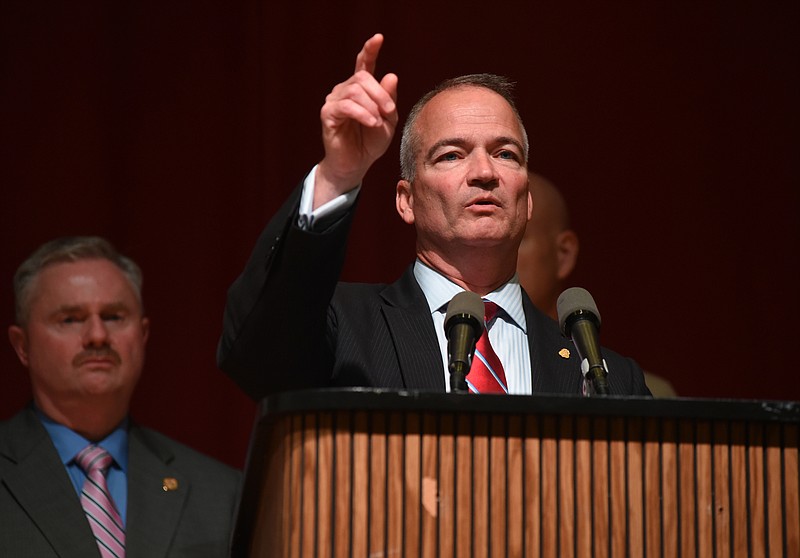

"He is being treated as a homegrown violent extremist," said FBI Special Agent Ed Reinhold.

Terrorists, by definition, are killers with an ideological agenda, experts say. They intend for their violence to send shock waves, to strike fear and influence policy.

Yet, so much is still unknown about Abdulazeez's intent, although it is clear his faith played a significant role in his decision to arm himself, fire into a military recruitment center and then ram into a military base and kill five service members.

On Wednesday, investigators skirted all questions about motive. Reinhold wouldn't answer questions about widely publicized reports that Abdulazeez struggled with depression, alcohol and drug dependency and that he was plagued by shame over the loss of his job in 2013 and a recent arrest and DUI charge.

Still, Reinhold did say federal officials believe the 24-year-old acted alone and they are looking into the possibility that he was self-radicalized.

"There are no indications that he had help," Reinhold told a large group of reporters Wednesday. "We're still in the early stages of figuring out what happened. Don't jump to conclusions."

One thing remains a mystery: Did Abdulazeez have a long-standing plan to attack the military that had been taking shape since he began writing about his affinity for an al-Qaida leader abroad in 2013? Or was it a spontaneous, suicidal act aimed at achieving religious redemption, brought on by psychosis and depression and a mix of substances?

The details about the weeks and days leading up to his attack and death offer competing narratives.

Unlike many other mass killers, Abdulazeez had friends, but his friendships were limited, a spokesperson for the family said. He struggled socially because of the guilt he felt about his drug and alcohol use.

"In a way, it was a self-imposed isolation," said the spokesperson, who asked not to be identified.

After his DUI arrest in April, his picture was published in the local newspaper and in "Just Busted," and family and friends have said he was deeply embarrassed. Before he lied to his parents by saying he was leaving Chattanooga on Tuesday to go on a work trip, there were multiple conversations between family members about the DUI and the upcoming court date on July 30.

Yet, even though he carried a sense of shame about not being able to act in accordance with his Muslim faith, he didn't appear to be more ideological than usual.

He fasted during Ramadan, but didn't appear to be more observant, the spokesperson said. The Washington Post reported that he did tell friends he was upset about the bloodshed in the Middle East and blamed U.S. policy, but that concern and frustration didn't seem to signify murderous intent.

On July 11, Abdulazeez bought ammunition for his guns, but he often stocked up on ammo because he liked to go to the gun range with friends, the family spokesperson said. He hunted rabbits and squirrels growing up and called himself a "Muslim redneck."

And his friends told the Washington Post that earlier this year he purchased several military-style assault weapons - AK-74 and an AR-15 a Saiga 12 pistol-grip shotgun - and drove to the Prentice Cooper State Park to practice at the gun range. But a lot of men in Chattanooga share the same hobby. Still, the guns upset Abdulazeez's father. So Abdulazeez chose to hide other guns.

Since the attack, Abdulazeez's blogs have been cited and used to argue that the Thursday attack was premeditated. He wrote on July 13 - three days before the killing - that some people thought that the Sahaba, the companions of Muhammad, were priests "living in monasteries" but that that wasn't true. "Everyone one of them fought Jihad for the sake of Allah. Everyone one of them had to make sacrifices in their lives."

In the next post, he called for action.

"Brothers and sisters don't be fooled by your desire, this life is short and bitter and the opportunity to submit to Allah might pass you by If you make the intention to follow Allah's way 100 percent and put your desires to the side, Allah will guide you to do what is right."

He told family and friends about the blog, and the spokesperson said that if he hadn't committed mass murder his writings would be considered fairly benign by other Muslims.

Before Abdulazeez left his parents' house in Hixson on July 14, his friends told the family that he was acting normally. He wanted to show off the convertible Mustang he rented and race it. He seemed in the mood to party, the spokesperson said.

But his friends said that Abdulazeez stayed out until 3 a.m. on the Tuesday night before the attack, as part of a drug-and-alcohol bender.

The next day, the family spokesperson said, Abdulazeez Googled martyrdom and whether he could be absolved of his sin if he became a martyr. The FBI has yet to release any information found on his computer or cell phone.

And on the same day, he exchanged texts with a friend about faith, the Washington Post reported.

His friend was expressing frustration, not knowing how to balance his Muslim faith with what was required of him at his job, including serving bacon to customers. Abdulazeez responded by quoting the prophet Muhammad. "Whosoever shows enmity to a Wali (friend) of Mine, then I have declared war against him."

With what they know, although there is still more to learn, the family doesn't believe that Abdulazeez was plotting his Chattanooga attack.

"We don't think this was a plan," the family spokesperson said.

In the end, the case may never be labeled as terrorism, said Jack Levin, a criminologist at Northeastern University, who had studied mass murders, including domestic terrorism, for 35 years and written multiple books on the topic. Officials are careful with the term, he said.

"We are not of one mind when it comes to defining terrorism," he said. "The FBI is usually reluctant to label a murder as an act of terrorism. If it is a terrorist episode then they have to assume responsibility. Why should they be responsible for something that is not within their purview?"

Still, the traditional idea of terrorism is evolving, said Charles Kurzman, a sociology professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Post 9/11 terrorists were organized, immigrant radicals who came to the U.S. for the purpose of destruction and death, laying in wait for their moment to strike. But the attack on Fort Hood in Texas in 2009, in which a U.S. army psychiatrist killed 13 people and injured 30 others, and the attack on Chattanooga seem to illustrate a new wave.

In the case of Fort Hood, the killer, Nidal Malik Hasan, had sent emails back and forth with al-Qaida leader Anwar al-Awlaki, the same Yemen-based imam who Abdulazeez followed on Twitter and wrote about after he was fired from his job in Ohio.

Yet, whether the attack was classified as terrorism has been heavily debated. The military initially called it an incident of "workplace violence," but earlier this year the victims were awarded the Purple Heart after years of debate over whether the shooting could legally be considered terrorism.

"We are seeing a shift away from large-scale elaborate attempts to use weapons of mass destruction or other high profile plots - the hallmark of al-Qaida and its affiliates - toward a lower tech do-it-yourself strategy that is being propagated by the self declared Islamic state," said Kurzman.

Contact staff writer Joy Lukachick Smith at jsmith@timesfreepress.com or 423-757-6659.

Read more about the attacks on Chattanooga military facilities

DesJarlais' bill to allow military to carry firearms at recruiting centers passes Senate

Memorial concert for fallen Marine Skip Wells this Saturday

Charleston, Chattanooga joined by tragedy, love

Instinct, basic training helped Marine save daughter during July 16 attack

Cooper: Marine Corps report revelations strengthen need for carry policy

Chattanooga Heroes Fund exceeds $1 million in donations

U.S. Women's World Cup team raises $60,000 to benefit the Chattanooga Heroes Fund

Chattanooga gunman test drove Lexus convertible before July 16 attack

Crowds pack Ross's Landing for tribute to five slain servicemen

Two months after July 16 attack, many questions remain unanswered

Jackson returns to hometown for today's tribute to five fallen heroes

Trace Adkins, Colt Ford, Aaron Lewis added to Chattanooga Unite benefit

Greeson: Chattanooga Unite offers all of us a chance to remember

July 16 shooter had no hard drugs in his system during April DUI arrest, lab results show

U.S. Marines will not arm recruiters in wake of July 16 attack

Photos: Run of Honor benefit race

Harry Connick Jr. added to Chattanooga United event

Kennedy: Angels of the flag garden

Tribute rises: Massive sculpture celebrates lives of Chattanooga's five fallen heroes

Greeson: UTC to honor five military heroes from July 16

Cook: Grief and the violence of July 16

Navy launches official investigation into Chattanooga attack

New bill would grant immunity to armed TN National Guard members

Muslims lead donations to families in Chattanooga shooting at Nashville event

Samuel Jackson to emcee benefit concert for July 16 attack victims

Makeshift Lee Highway memorial to servicemen cleared

Permanent memorial to slain servicemen on Lee Highway

A gunman warped our history, now we must shape our future

Vice President Joe Biden honors Chattanooga shooting victim and promises: 'America never yields'

Chattanooga slayings prompt state, federal changes on military members being armed in U.S.

The moment the call comes in: responding to an active shooter

Berke: Moments of crisis revealed Chattanooga character

Chattanooga Can Build On Unity

Biden calls shooter 'perverted jihadist' at memorial in Chattanooga

Chattanooga holds memorial service for fallen service members

Biden to speak at Chattanooga memorial service, security heightened

Pam's Points: Weekend of tributes can lead to healing

Concert to benefit shooting victim's families Sept. 16

Details falling into place for Biden visit, memorial to Chattanooga's fallen heroes

Greeson: A weekend filled with reasons to forever remember all our heroes

Secret Service orders all Chattanooga traffic cameras to go dark Saturday

Photos: UTC retires flag that flew at half-staff in mourning for Chattanooga's fallen five

Vice president to attend ceremony honoring five fallen military servicemen

Sixty-five-foot-tall sculpture will commemorate victims of July 16 attack

Tennessee Senate Republicans: Radical Islam is the enemy

Cruz says if he becomes president he'll stop trend of 'radical Islamic terrorism'

Memorial for slain servicemen to be held Saturday

Top Pentagon brass to attend one-month anniversary of Chattanooga attacks

Wiedmer: World Cuppers' exhibition can still help our fallen heroes

Kimball approves assistance donations, including Chattanooga Heroes Fund

Chattanooga Sings for Hope concert raises money for victims' families

Motorcyclists go on charity ride to honor slain Marine

An open letter to Chattanooga from Adm. Jonathan W. Greenert

Healing but scarred: Marine wounded in July 16 attack back to recruiting

Hundreds in Arkansas gather to remember slain Marine Staff Sgt. David Wyatt

Permanent memorial will be dedicated on one-month anniversary of July 16 attacks

Navy plans to station armed guards at reserve centers across U.S.

Some recruiters will be packing 9 mm handguns under new Tennessee guidelines

Guardsmen with valid permits can now carry guns at facilities

FBI scales back its presence in Chattanooga following July 16 rampage

GOP pushes back on 'politically correct' labeling of extremist attacks

Wiedmer: Let U.S. Soccer be a Chattanooga hero

Local artist to paint mural honoring slain military servicemen

Chattanooga Sings For Hope concert remembers the fallen, honors first responders

Al-Qaida calls for more lone wolf attacks, praises Chattanooga shooter

Haslam: Most Americans wouldn't resent serviceman for shooting at Abdulazeez

Petition to honor servicemen who fired personal weapons at Chattanooga gunman hits 20,000 signatures

Navy: Officer has not been charged for firing personal weapon at Chattanooga gunman

An offering of art: Illinois artist responds to Chattanooga shootings

After July 16, tragedy became politics

What's in a name? The absence of terror label after attacks sparks national debate

Ali: Mentally disturbed, Muslim criminal

Families of the five slain military servicemen receive donation of nearly $120,000

July 16 tragedy united community and brought out Chattanooga's best

Charitable cottage industry springs up in wake of shooting rampage

Navy officer confirms he shot at Abdulazeez with his personal weapon

Bond between Chattanooga, Port Angeles grows: 'It's almost like we're sister cities'

Business Bulletin: Fundraiser scams hit Chattanooga area in wake of tragedy

Insane Paintball/Airsoft game benefits Chattanooga shooting victims fund

Defense secretary calls for review of security policies in wake of Chattanooga shootings

Port Angeles woman presents Chattanooga mayor with 20 sympathy banners

White House petitioned to honor Chattanooga servicemen who fired back at gunman

Chattanooga Freedom Float planned to raise money for heroes in July 16 attack

FBI, NCIS search banks of Tennessee River off River Canyon Road

Chattanooga Marines return to work after attack

Port Angeles group hand-carries 16 signed sympathy banners to Chattanooga

Last of the five slain military servicemen is laid to rest at National Cemetery

The funerals are over, but closure is ongoing

Dropkick Murphys honor fallen Massachusetts Marine

See the DUI arrest of Chattanooga gunman Mohammad Abdulazeez

Hits 96 honoring slain service members with concert featuring MKTO and Karmin

Public lines up to honor Petty Officer 2nd Class Randall Smith

Gunnery Sgt. Thomas Sullivan is laid to rest in Massachusetts hometown

Fleischmann announces bill to award Purple Hearts to shooting victims

Are we helping extremists recruit our lost children?

No easy answers forthcoming when the mind's involved

Funeral procession for Navy Petty Officer Randall Smith announced

Funeral held for Chattanooga shooting victim Sgt. Thomas Sullivan

The youngest hero: Thousands gather for funeral of Skip Wells

Bravo Network star visits Chattanooga, lends some of her ample strength to wounded community

Smith: Beauty through Brokenness – Chattanooga's Choice

'His life made a difference,' Hundreds mourn Atlanta Marine slain in Chattanooga

After the vigils, the real work begins

Homegrown: The new threat to America comes from within

As threats to Muslims mount, Pentagon asks civilians to stand down

Mother of Sgt. David Allen Wyatt says thanks to Chattanooga

Gerber: A national tragedy in our backyard

Healing Chattanooga, one life and brick at a time

Chattanooga will prevail after tragedy and other letters to the editors

Visitation continues for Cpl. Squire 'Skip' Wells; 2nd Class Randall Smith's body in Nashville

Wisconsin town says goodbye to Marine slain in Chattanooga

Pentagon asks armed volunteers to stop guarding U.S. military recruiting centers

Multitudes gather to mourn and honor fallen Marine Staff Sgt. David Wyatt

Baptists show support by visiting local Mosque for Friday prayers

Greeson: Elected officials should start planning memorial

Body of slain Massachusetts Marine returns home

Mourners gather to pay respects to slain Georgia Marine

Tennessee River 600 to honor fallen servicemen on Sunday

Body of slain Marine being laid to rest at Chattanooga's National Cemetery

Funeral arrangements made for Navy Petty Officer Randall Smith

Mike Battery Marines recount heroic actions during rampage at Amnicola reserve center

'Run!' Quick response key to survival in first attack at recruitment office

Funeral for Staff Sgt. Wyatt is today; public invited to line roadside along procession route

Cook: Four poems about the last seven days shared to ease city's pain

Chattanooga's broad middle helps city bear tragedy

Gunning for safety? Military leaders say no

Peyton Manning adds muscle to fundraising for families of shooting victims

Tennessee ramps up handgun permitting for Guard, but can they bring firearms to work?

Friends rally around Hindu businessman subjected to nasty Facebook gossip

Moment of radio silence held in remembrance of service members killed

Mississippi National Guard recruiters returning to 10 sites

Civilian accidentally fires AR-15 rifle at Ohio military recruiting station

Navy has memorial in Virginia for Tennessee shooting victim

Marines moved citizens in the Riverpark away from shooter

Four misconceptions about the Chattanooga shooting

Tennessee lawmakers to meet next month to assess the state's security status after Haslam directives

Jordan releases uncle of Chattanooga gunman without filing any charges

Funeral plans set for all five slain service members

City Beat: I'm thankful cops sometimes go against human nature

Tunes for tragic times: Sad songs say so much

Hixson Flight Museum plans flight flight to salute fallen Marines and sailor

FBI searches woods at intersection of Highway 153 and Amnicola

Chattanooga declares shooting sites, funerals and memorials off-limits to protesters

Lance Cpl. Skip Wells' body to be escorted this afternoon

Peyton Manning launches Chattanooga Heroes Fund to honor shooting victims

Sgt. Thomas J. Sullivan to be buried in hometown

Minute by minute: A timeline of the Chattanooga attack revealed

Terrorist or extremist, was Abdulazeez a man with a plan?

Gov. Haslam moves National Guard recruiting offices to armories

Clipping and snipping, volunteers prepare donated flowers for Marine's last rites

'Best Town Ever' rival reaches out in sympathy to Chattanooga

Greeson: Reason why we are the Best Town Ever -- all of you

City's church bells to chime on one-week anniversary of shooting

Video: Five of the Marines who survived Chattanooga attack tell their story

Kentucky to enhance security at National Guard bases and recruitment offices

Ohio starts to arm recruiters in wake of Chattanooga attack

Tennessee moves recruiters to National Guard armories

Armed citizens flock to recruiting centers to stand guard

FBI explains how Chattanooga shooting played out, how Mohammad Abdulazeez was killed

Corker gets choked up, pauses in Senate while honoring slain servicemembers

Armed citizens flock to recruiting centers to stand guard

Port Angeles residents sign giant card for Chattanooga after deadly shootings

Pentagon rejects calls to arm all U.S.-based military personnel

FBI calls Chattanooga shooter a homegrown violent extremist

After Chattanooga shootings, armed citizens guard recruiters

How will last week's attack affect Chattanooga's brand?

'Mike Battery is here': After loss, Marines regroup, move forward

Fighting for our fighters: Erlanger trauma team called to front lines on day of shootings

'God bless these American heroes,' Obama says in day of tribute, remembrance for fallen

Marietta, Ga., residents honor hometown hero killed in tragic attack

Duke's basketball coach provides 'bright spot' for fallen sailor's family

Services set for two slain Marines

Cook: The universal wound of Lee Highway

The more we learn, the less we understand

Gov. Walker issues order to arm Wisconsin National Guard

In West Virginia, 2 armed men stand outside recruiting center

Virginia governor asks for more patrols at recruiting centers

Crowd gathers to mourn Georgia victim in Chattanooga attack

Navy officer, Marine shot at Chattanooga gunman, according to report

Council seeks to ban protesters from funerals of five slain servicemen

Flags at half-staff in South Carolina, again

Chattanooga mayor: we owe these five heroes and their families a deep debt of gratitude

FBI raids apartment of Muslim family at Mountain Creek Apartments

Shooter's family denies reports that Jordanian uncle is tied to Chattanooga attack

Obituary for Sgt. Carson Holmquist

Two slain servicemembers will be laid to rest in Chattanooga

Chattanooga shootings photo galleries

Supercuts stores in Chattanooga offer special haircut prices for military and police

Alabama sheriff urges citizens to take up arms to defend against lone wolf attacks

Marine Corps trainee sees man shot, pulls over and stops bleeding

Obama orders flags flown at half-staff

President, senators honor shooting victims

UPDATED: Lawyer says Chattanooga shooter's uncle detained

Abdulazeez followed a radical member of al Qaeda

Flags lowered at U.S. Capitol, Obama could lower White House flags today

Armed volunteers guard Murfreesboro recruiting center

Makeshift memorials grow as a city moves through waves of grief

Local gun sales spike after attacks on military sites in Chattanooga

Answers elusive as different sides of Mohammad Abdulazeez's life emerge

Public Defender Steve Smith stands by Facebook comments following attacks

Fleischmann 'disappointed' because White House hasn't lowered U.S. flag

Cook: The semantics of terrorism and the quest for peace

Looking for peace? Don't ask Steve Smith

Tweak gun policy for military installations

DesJarlais: Bill arming military personnel needed because Pentagon directive falls short

U.S. flag sales soar in Chattanooga after shooting

Two area legislators issue call for action on slaying of four Marines, sailor in Chattanooga

Military directs security upgrades at facilities after Chattanooga shootings

Gov. Bryant OKs Mississippi Guard to arm personnel

Chattanooga shooting prompts Nebraska Guard to arm personnel

Chattanooga attack was an act of terror, Rep. Chuck Fleischmann says

Republicans ask Missouri governor to arm National Guard

Shooter's diary paints a disturbing picture

Arkansas governor temporarily closes state's nine National Guard recruitment offices

South Carolina joins other states in arming National Guardsmen

Iowa to review security at National Guard facilities in wake of Chattanooga attacks

Madisonville man arrested at Lee Highway memorial

Muslim blogger quoted by gunman in yearbook speaks out

U.S. military tells recruiting centers to step up security by closing blinds

One of the Marines killed Thursday may have carried a privately owned Glock

Crowd awaits Westboro Baptist protesters at Chattanooga shooting memorial on Lee Hwy.

Tennessee representative calls gunman Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez a 'jihadi'

Flags to remain at half-staff until sunset on Friday

Wiedmer: Peyton a welcome visitor for our town's finest

Honoring the dead: Rally, memorial, hearse motorcade pay respects to shooting victims

Governor Haslam orders review of safety measures at Tennessee military facilities

FBI looking into shooter's possible involvement with ISIS

Hundreds rally in motorcade for the shooting victims

Family spokesman: Depression dogged Chattanooga gunman

Friends mourn U.S. Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Randall Smith, shot to death in Chattanooga shooting

Cook: In the big heart of Chattanooga

Family of dead Chattanooga gunman breaks silence

Marine commander: 'Heroic acts by our Marines on that day'

Will the shooting change life for Chattanooga Muslims?

Tennessee pauses as other states quickly arm Guardsmen in wake of Chattanooga attacks

Friends say Chattanooga shooter was changed by trip to Middle East

Father of Chattanooga shooter says he was blindsided by son's actions

Chattanooga Muslims anxious after shootings

Chattanoogans puzzling out answers, pouring out grief

Semper Fi: Remembering the fallen in the Chattanooga attacks

DesJarlais, others say gun restrictions should be lifted at military buildings

Groups raising funds for shooting victims, families

Greeson: Trying to comprehend incomprehensible acts

Chattanooga shock moves to soul-searching

Front lines collided in Thursday's horror

Wiedmer: Former Red Bank student's acts leave ex-wrestling teammates in shock

More than 1,000 attend interfaith memorial service for slain Marines

Remains of fallen Marines to be given same honors as those killed in action

Shooter worked at nuclear power plant before failing background check

U.S. House Chairman says Chattanooga slayings now officially a terrorism investigation

Shooter came from troubled family, divorce papers show

Slain Marine's last text to his girlfriend warned of gunman's assault

Fallen Heroes: What we know about the four men who gave all for their country

Who was Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez?

UTC students, local community mourn at prayer vigil

Minute-by-minute coverage of the Chattanooga shooting that killed four Marines

Chattanoogans reach out on Instagram after tragic shooting

Timeline of terror in Chattanooga shootings

Community grieves, gathers for prayers in wake of tragedy

Nightmare for city: Federal investigation vowed after four Marines killed in shooting

Sympathy for victims pours in following Chattanooga shootings

Eyewitnesses recount moments of violent tragedy

Latest national news on Chattanooga shootings: authorities searching gunman's computer

Cook: On a normal Thursday morning, everything changed