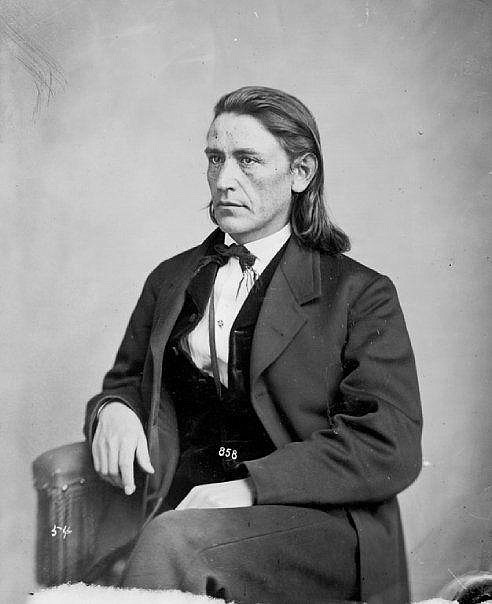

If Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross hoped that his people and their land would be saved from removal and occupation through legal routes available to citizens, he found that hope evaporating quickly. Even within the ranks of the Cherokee, there were leaders who felt that removal was inevitable and that they should take the monies offered and simply withdraw from the controversy. Ross, instead, clung to the Cherokee's historic position, believing that it was the will of their "fathers;" Cherokee lands would never be for sale.

President Jackson, seizing on the division within the Cherokee nation, attempted to remove Ross from the conversation, using legal maneuvers and the strategic use of monies. He offered to pay the Cherokee Nation $2.5 million for their lands or $3 million if they would pay to transport themselves to the Oklahoma territory. While the offer amounted to almost 50 cents per acre, Ross realized that the lands were far more valuable, even as he opposed the sale.

When Major John Ridge sent a letter to Ross endorsing the move by saying " it is admitted that we can't be a nation here, I hope we shall attempt to establish it somewhere else! Where, the wisdom of the nation must try to find," Ross began to fear that his people had grown weary of the uncertainty and the fight. Even Alexis de Tocqueville, who traveled around the United States in his exploration of "Democracy in the New World," noted that "if by chance an Indian nation can no longer live within its territory, the Americans offer a fraternal hand to lead the natives off to die somewhere other than in the land of their fathers To destroy human beings with greater respect for the laws of humanity would be impossible."

The great mass of the Cherokee people remained loyal to their chief but the powerful voices within the Cherokee Nation, including Ridge, Elias Boudinot, editor of the Cherokee Phoenix and even Ross's own brother, argued that they could not win the fight.

Ross felt the pressure to launch a final effort to save his peoples' lands. In early 1834, he journeyed once more to Washington, D.C. Upon arrival, he sent President Jackson a letter. "The undersigned Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, in behalf of himself and the Cherokee delegation, present their respects to the President of the United States and beg leave to inform him that they are desirous to have an interview with him, for the purpose of having a free and full conversation Jno. Ross." The president agreed to see the delegation two days later, and an unwell Jackson received them on Feb. 5.

Ross and the Cherokee appealed for intervention in Georgia's attempt to "remove them from their lands," and Jackson once again explained that he was "powerless." After a few moments of conversation and refreshments, he dismissed them. When an opposition Cherokee delegation gained an audience with the president only days later and offered to work with him in executing a "removal solution," Jackson knew Ross had a rebellion brewing among his own people and was no longer the voice of a unified opposition.

Ross sent one more carefully and beautifully written letter to the president, appealing to times spent fighting together.

"Twenty years have now elapsed since we participated with you in the toils and dangers of war It is in the hour of such times that the heart of man can be truly tested and correctly judged. We were your friends Now in these days of profound peace, why should the gallant soldiers which in times of war walked hand in hand thro' blood and carnage, be not still friends? We answer that we are yet your friends."

He then offered a solution that far exceeded the negotiating power authorized by the Cherokee Legislature: "Will you agree to enter into an arrangement on the basis of the Cherokees becoming prospectively citizens of the United States provided the Nation will cede to the United States a portion of its territory for the use of Georgia? And will you agree to have the laws and treaties executed and enforced ?"

Was John Ross simply stalling as he contemplated a different solution or was he looking ahead to the end of Jackson's presidency? Either way, the storm clouds darkened.

Linda Moss Mines is the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Historian, a member of the Tennessee Historical Commission and the Regent, Chief John Ross Chapter, NSDAR.

Read more Chattanooga History Columns

- Gaston: Paul John Kruesi was Edison's right-hand man

- Robbins: The old Richardson's house and the Civil War

- Gaston: James Williams was a man of the world

- Raney: Mason Evans, the 'Wild Man of the Chilhowee'

- Gaston: The legacy of Adolph Ochs endures

- Martin: Ed Johnson said, 'I have a changed heart,' the day before his lynching in Chattanooga on 1906

- Thomas: The inventiveness of Judge Michael M. Allison

- Moore: Chattanooga's first Chinese community

- Summers, Robbins: Chattanooga's Tuskegee Airman - Joseph C. White

- McCallie: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says so!

- Gaston: John McCline's Civil War - from slave to D.C. parade

- Raney: Exploring Chattanooga businesses in the Green Book

- Elliott: Remembering the Freedmen's Bureau in Chattanooga

- Gaston: Nancy Ward was a beloved, respected Tennessean

- Martin: Prohibition - the noble experiment

- Elliott: 'A shameful, disgraceful deed': The destruction of the Sewanee cornerstone

- Gaston: Robert Cravens was ironmaster, Chattanooga area's first commuter

- Robbins: Dr. T.H. McCallie's Christmas 1863

- Robbins: Journalist writes of a trip to Missionary Ridge in 1896

- Summers, Robbins: Mine 21 disaster - gone but not forgotten

- Elliott: Collegedale incorporates to avoid Sunday 'blue laws'

- Gaston: 'Marse Henry' Watterson's journalism fame began in Chattanooga

- Robbins: Orchard Knob battle recalled in 1895

- Elliott: Chattanoogans joined in an 'orgy of joy and gladness' on Armistice Day, 1918

- Thomas: Noted service, speakers are marks of Rotary Club of Chattanooga since 1914

- Summers and Robbins: Remembering noted Tennessee author North Callahan

- Raney: 'I auto cry, I auto laugh, I auto sign my autograph'

- Gaston: Sequoyah's alphabet enriched Cherokees

- Robbins: A look at Sam Divine's life during the Civil War

- Robbins: Memories of a Confederate nurse

- Robbins: More notes from Bradford Torrey's 1895 visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Robbins: Journalist in 1895 details visit to Chickamauga Battlefield

- Elliott: Telephone exchange firebombing was distraction for grocery store robbery

- Gaston: Worcester brought Christ's message to Cherokee at Brainerd Mission

- Robbins: 1896 travel diary: 'A Week on Walden's Ridge'

- Gaston: Elizabeth Strayhorn, WAC Commandant at Fort Oglethorpe

- Robbins: The history of the Friends of Moccasin Bend National Park

- Moore: Do you own a Sears Roebuck home?

- Summers and Robbins: Camp Nathan Bedford Forrest in World War II

- Gaston: Hiram Sanborn Chamberlain remembered

- Elliott: Daisy the center of tile, ceramic manufacturing in Hamilton County

- Gaston: FDR inaugurates the Chickamauga Dam

- Summers, Robbins: Interned WWII Germans had it easy at Camp Crossville

- Elliott: A war correspondent on Lookout Mountain

- Gaston: Chickamaugas finally bury hatchet in Tennessee Valley

- Gaston: Chickamaugas in Chattanooga

- Robbins: The history of the Riverbend festival

- Raney: Sadie Watson, the first woman elected in Hamilton County government

- Moore: Remembering Chattanooga's Hawkinsville community

- Elliott: Welsh coal miners transformed Soddy after the Civil War

- Gaston: Chattanooga's best-kept secret

- Elliott: Cabell Breckinridge loses his horse

- Raney: Martin Fleming is the people's judge

- Gaston: The amazing career of Francis Lynde

- Martin: Hamilton County's Name Sake: Alexander Hamilton

- Summers, Robbins: The crosses at Sewanee

- Bledsoe: The fiery truce at Kennesaw Mountain

- Moore: Talented architect's life cut short by tragedy

- Rydell: Chattanooga's place in soccer history

- Robbins: Tennessee Coal, member of the First Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Raney: In the barber chair

- Lanier: Becoming the Boyce Station Neighborhood Association

- McCallie: John P. Franklin: Living history among us

- Barr: Chattanooga's first railroad: The Underground Railroad

- Summers, Robbins: Charles Bartlett was a Pulitzer Prize winner, Kennedy confidant

- Rainey: 'We have seen it'

- Elliott: Feinting and fighting at Running Water Creek and Johnson's Crook

- Gaston: The Spring Frog Cabin at Audubon Acres

- Raney: Wauhatchie Pike was moonshine motorway

- Robbins: Oakmont was home of venerable Williams clan

- Summers and Robbins: Rebirth of the Mountain Goat Line

- Elliott: Bad investments led to Soddy Bank failure in 1930

- Summers and Robbins: Pearl Harbor attack left football behind

- Gaston: Jolly’s Island namesake had long ties with Sam Houston

- Return Jonathan Meigs, Indian Agent

- Moore: Did you know about St. Elmo's other two cemeteries?

- Summers: Orme - Marion County's almost lost community

- Davis: Spooky revival at Sharp Mountain in 1873

- Robbins: The story of Longholm

- Raney: Women labored to help the U.S. win World War I

- Even in the city, the 'wheel' changed everything

- Murray: Confederate dilemma after Chickamauga

- J.B. Collins — Newsman extraordinaire

- Robbins: The Story of the Lyndhurst Mansion

- Chattanooga artist and wife lost on the Lusitania

- Chattanooga History Column: Battelle, Alabama and the Battelle Institute

- John Ross, a founder of Chattanooga

- Hamilton County casualties in World War I

- Chattanooga Power Couple

- 'Somewhere in France'

- The Ray Moss family

- Battery B from Chattanooga

- Ulysses S. Grant, Clark B. Lagow, and the Chattanooga Bender

- Songbirds Museum Timeline

- Hamilton County World War 1 roster

- The Soddy Girl and the Memphis Belle

- Blues icon Bessie Smith was the Empress of Soul

- Women's Army Corps at Chickamauga

- Emma Bell Miles' life at the top of the 'W'

- The Tivoli Wurlitzer is one of Chattanooga's priceless assets

- Chattanooga in struggle for freedom during Civil War

- October 1918, Chattanooga paralyzed by Spanish flu epidemic

- Eli Lilly and the Ditch of Death

- One hundred years ago, Chattanooga goes to war

- The legacy of Anna Safley Houston

- Harriet Whiteside was ahead of her time

- Southern Adventist University

- Chattanooga native's writings aided Civil Rights movement

- Zion College, Chattanooga's only African American College

- The North Shore's hidden past

- Mayme Martin -- Businesswoman and community leader

- Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom

- Top of Cameron Hill was price of rerouting interstate

- Cameron Hill has rich history

- Temperance movement included Harriman university

- The sweetest music this side of Heaven

- Conquistadors at Chattanooga

- Chattanooga and the 'General'

- Chattanooga's first Thanksgiving, 1863

- Chattanooga's greatest flood caught city unaware

- Opening the Cracker Line

- European trip in 1900 enlightens Sophia Scholze Long

- Sophia Scholze Long spoke out when others were silent

- Little South Pittsburg and its big silent movie stars

- Lot attendant recalls hottest job in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's Forest Hills is final resting place for known, unknown

- Burritt College -- Pioneer of the Cumberlands

- Chattanooga's nicknames trace city's evolution

- The 25th annual meeting of the Tennessee Press Association

- Clemons Brothers Furniture Store

- The Short Life of the USS Chattanooga

- Ellen Jarnagin McCallie lived a truly remarkable life

- Dr. Jonathan Bachman was a revered city father

- Second guessing the Confederate failure on Missionary Ridge

- Nancy Kefauver, ambassador for the arts

- William Gibbs McAdoo kept his Southern roots

- Chattanooga's Secretary of the Treasury

- Howard Baker remembered as a statesman/photographer who snapped history

- Tivoli's last picture show

- The history of one of Chattanooga's oldest businesses

- Chattanooga's roller derby skaters

- Myths of Coca-Cola in Chattanooga

- Chattanooga's neighborhood grocery stores

- The tale of the Scottsboro Boys

- The people's history of Chattanooga

- Howard School is Chattanooga's reminder of Reconstruction

- Elevator operator, painter, mystery man: meet Rice Carothers

- Raulston Schoolfield made enemies amid his rise to power

- Website lets users peer into Chattanooga's past

- The flood of 1917

- Chattanooga's 'wickedest woman' buried at Forest Hills

- History of Cummings Highway